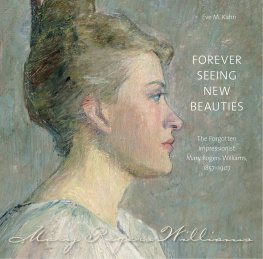

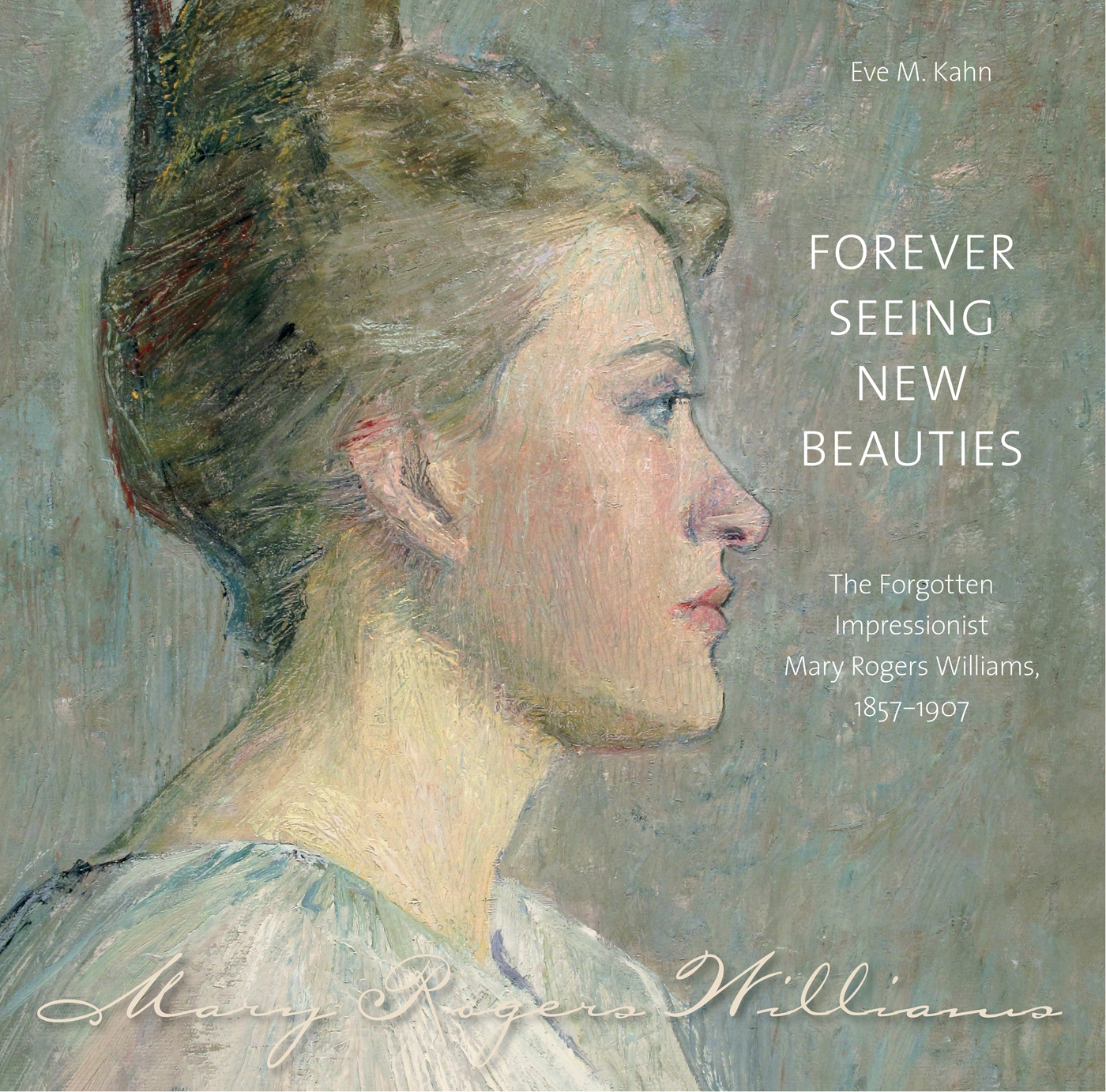

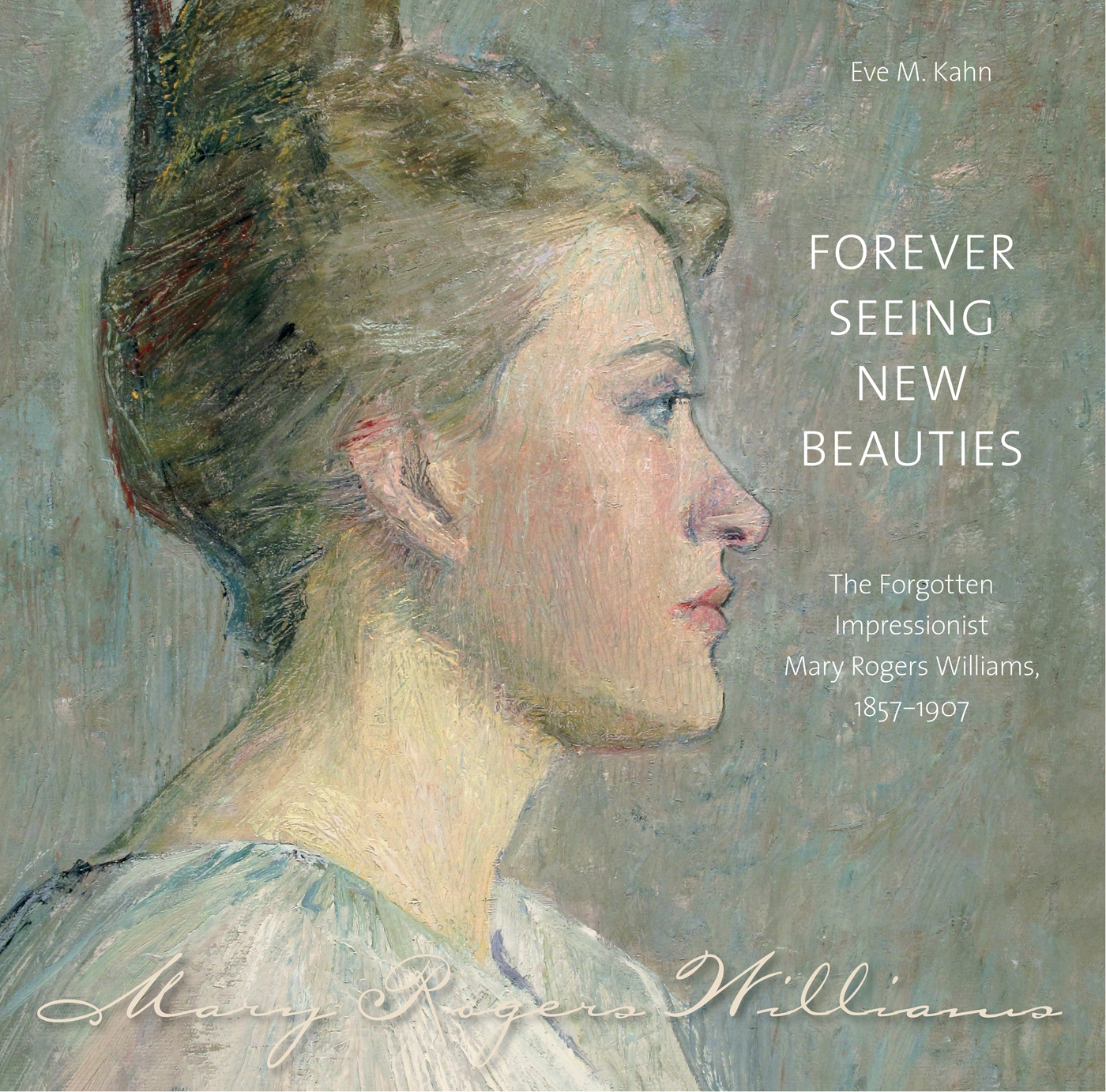

Forever Seeing New Beauties

A

Driftless Connecticut

Series Book

This book is a 2019 selection in the

Driftless Connecticut Series, for an

outstanding book in any field on a

Connecticut topic or written by a

Connecticut author.

Forever Seeing New Beauties

THE FORGOTTEN IMPRESSIONIST MARY ROGERS WILLIAMS, 18571907

Eve M. Kahn

Wesleyan University Press | Middletown, Connecticut

Wesleyan University Press

Middletown, CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

2019 Eve Kahn

All rights reserved

Printed in China

Designed and typeset in Cariola, Mrs. Eaves, and The Sans types by Chris Crochetire, BW&A Books, Inc.

The Driftless Connecticut Series is funded by the Beatrice Fox Auerbach Foundation Fund at the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request

Hardcover ISBN: 978-0-8195-7874-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-8195-7876-1

5 4 3 2 1

Frontispiece caption: Marys importance is partly due to quantities of surviving correspondence plus ephemera: dried flowers from her travels, scraps of her dresses, confetti from Paris parades. In a family locket, Marys photo is in the left compartment. PHOTO: KIMBERLY J. SCHNEIDER.

Front cover illustration: A Profile, c. 1895, oil on canvas, 21 16 inches, by Mary Rogers Williams (18571907).

To Mary, for writing and painting so beautifully;

to the Whites for preserving so much;

and to my family and friends,

for putting up with so much.

Contents

I.1 My art historian mother Rene Kahns mysterious landscape painting. AUTHORS PHOTO.

Introduction

The Funny Way I Stumbled upon Her

There is a punch line to this story, trust me.

From 2008 to 2016, I wrote the weekly Antiques column for the New York Times. I reported on exhibitions, sales, and new scholarship related to anything old, from stone couches in ancient Etruscan tombs to 1960s civil rights posters. In April 2012, I devoted a column to shows and books about nineteenth-century American women artists. They hiked in bulky skirts to paint along European and American mountaintops, and they impressed exhibition juries from Chicago to Munich. A few weeks after it ran, under the headline These Women Refused to Stay in the Kitchen, I visited my mother Rene Kahn, an artist and art historian in Stamford, Connecticut.

She still lived in the 1830s farmhouse where I grew up, and she was still, as she had been since my 1970s childhood, bringing home interesting old things to research from estate sales and antiques stores. I asked her to remind me of the backstories of the signed artworks, so I could write them down for posterity. In the living room, a moody nineteenth-century landscape, an autumn scene of a forest pond, had hung for decades in a high-relief gold frame. The room is kept shady by the yards overgrown rhododendrons. I had never paid attention to the painting. My mother announced, Thats signed M. R. Williams, for Mary Rogers Williams. I looked her up once. She taught at Vassar, I think.

Mom, I just wrote a whole column about new research into nineteenth-century women painters, and you have one of their works and didnt tell me? She shrugged. She hadnt noticed my column topic, and, in any case, she told me, I bought it for the frame, the frame! She didnt particularly like the painting. She had found it at a tag sale in Cos Cob, Connecticut, which had been an artists colony for American Impressionists; maybe it had belonged to one of Marys friends?

I.2 The palatial home in Waterford, Connecticut, where the White family has lived for a century, with Marys archives slumbering. AUTHORS PHOTO.

I felt a little proprietary: here was my familys very own forgotten woman painter.

I took photos of the piece and started researching Mary. The pitiful internet trail conflicted about her dates of birth and death1856? 1857? 1906? 1907?and her place of death: Florence? Paris? Benezit, the exhaustive dictionary of artists, noted only that she was a student of Dwight W. Tryon and William Merritt Chase. Nothing of hers had been exhibited in a century except for her portrait of her painter friend Henry Cooke White (18611952); it had been shown in a 2009 survey of Whites pastels at the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut. The museum complex contains the ancestral home of Florence Griswold (18501937), who used it as a boardinghouse frequented by artists. I called the museum to ask if anyone knew anything about Mary, and they put me in touch with Henry Whites grandson, Nelson Holbrook White, known to all as Beeb, who had become an artist in the footsteps of his father, Nelson Cooke White (19001989).

Beeb had learned about Mary from his grandfather. Youre doing good research, because not too many people have heard of hershes pretty much into oblivion, he told me. She ran Smith Colleges art department under Tryon, who was Henry Whites close friend. She was the nuts and bolts of the teaching, Beeb explained. His grandfather, he said, was so fond of her and admired her as a painter. The family had inherited many of her works and always believed these are really good quality, hold on to them, they may come into their own someday. Some of the paintings were stored at his home in Waterford, Connecticut, and he invited me to visit. My curiosity was piqued, so off I went a few weeks later.

Henry, I eventually learned, was a Hartford native who had been a friend of Miss Florence (as everyone called her) and her circle. He built homes for his family in Waterford, a beach hamlet about fifteen miles from the Griswold boardinghouse. Other bohemians, plus less interesting businessmen, set up summer places nearby in what is now a historic district called the Hartford Colony.

I met Beeb at the New London train station. He was wiry, courtly, and tanned, and he had a Yankee accent that is a priceless antique in itself. He brought me to the house that Henry built, a gorgeous pile in shingles and stone designed by the Main Line Philadelphia architect Wilson Eyre. It has long belonged to Beebs brother George, a hearty and jocular intellectual who founded Waterfords Eugene ONeill Theater in the 1960s with his wife Betsy. (I have met not a single uninteresting person on the Mary trail!) On a breezy porch overlooking the Sound, George showed me what he had found a few minutes before: a box covered in faded floral fabric, with a handwritten label listing the contents as Mary Williams Letters circa 1895, 1906 / Died in 1907.

I opened it, trembling. Inside was the first batch of hundreds of Marys letters that were about to consume my life. I somehow remembered to take photos of the box before and after I lifted the lid, foreseeing how big the moment would be.

The trove was in the houses Archive Room, among boxfuls of correspondence and artwork from generations of Whites and their cultured friends. Two more boxes of Williams papers turned up that day, and more batches have emerged year after year.

With the opening of that fabric box, Mary Rogers Williams instantly changed before my eyes from a mystery, and someone I felt sorry for, into someone waiting to be documented based on thousands of unread pages.

Next page