Also by H. W. Brands

T.R.

The First American

The Age of Gold

Lone Star Nation

Andrew Jackson

Traitor to His Class

American Colossus

The Man Who Saved the Union

Reagan

The General vs. the President

Heirs of the Founders

Dreams of El Dorado

The Zealot and the Emancipator

Our First Civil War

Copyright 2022 by H. W. Brands

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

All photographs are courtesy of the Library of Congress.

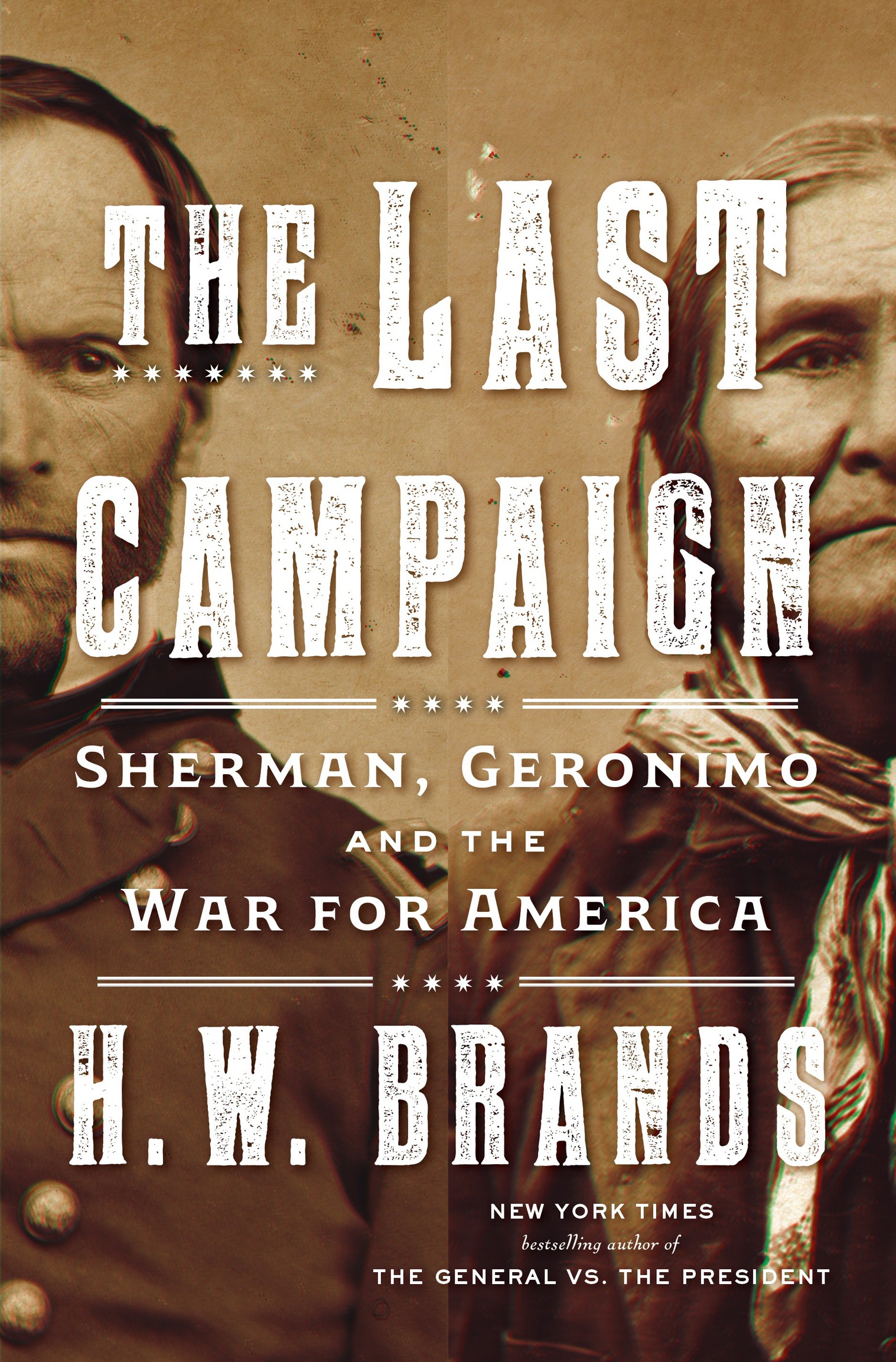

Cover photographs: Major General William T. Sherman courtesy of Library of Congress; Geronimo courtesy of Oklahoma Historical Society; texture detchana wangkheeree / Shutterstock

Cover design by John Fontana

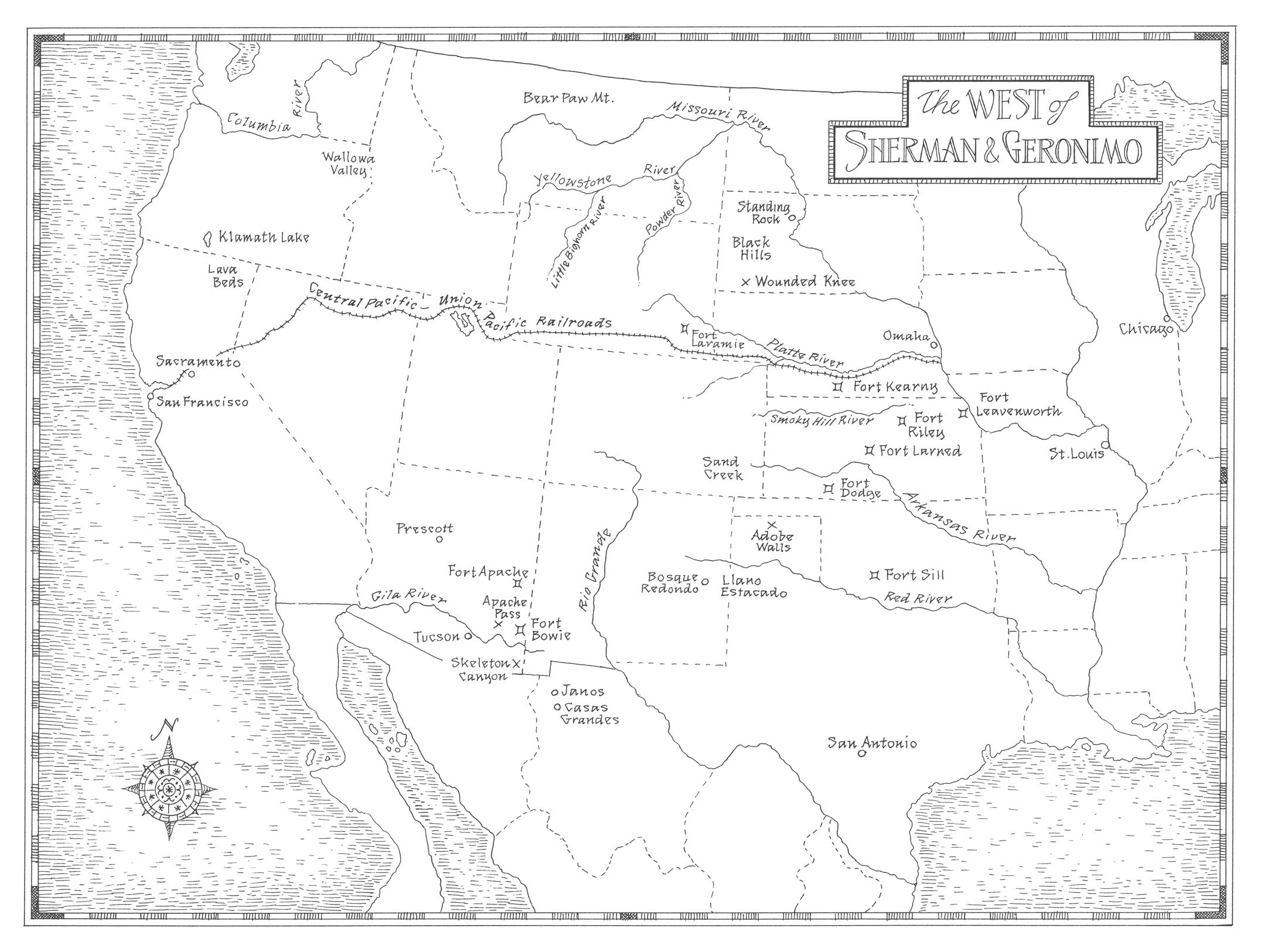

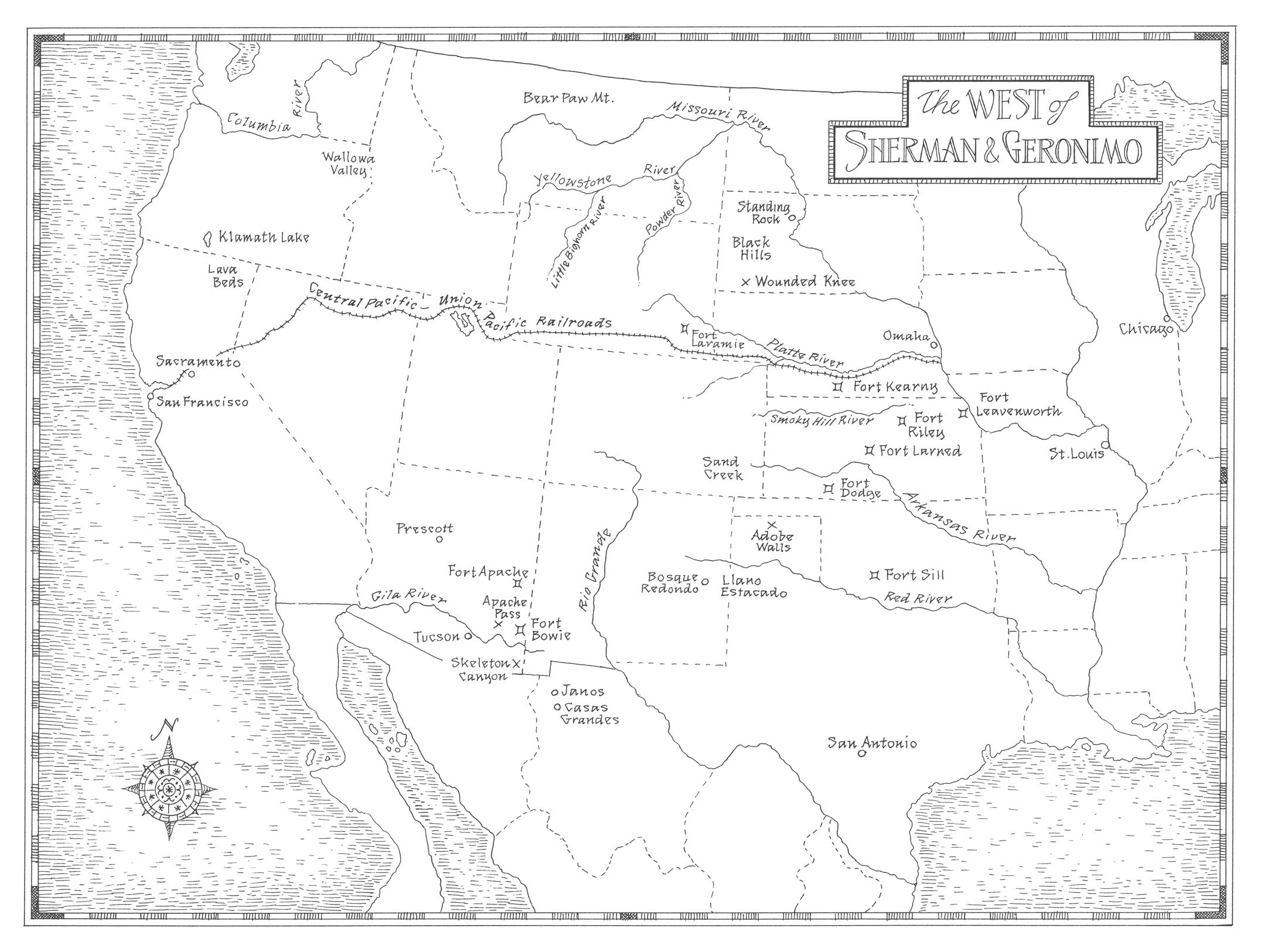

Map by John Burgoyne

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brands, H. W., author.

Title: The last campaign: Sherman, Geronimo and the War for America / H. W. Brands.

Other titles: Sherman, Geronimo, and the War for America

Description: First edition. | New York: Doubleday, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021051025 (print) | LCCN 2021051026 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385547284 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780385547314 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Indians of North AmericaWars18661895. | Geronimo, 18291909. | Sherman, William T. (William Tecumseh), 18201891. | GeneralsUnited StatesBiography. | Apache IndiansKings and rulersBiography.

Classification: LCC E 83.866 . B 835 2022 (print) | LCC E 83.866 (ebook) | DDC 973.8dc23/eng/20220331

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021051025

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021051026

Ebook ISBN9780385547314

ep_prh_6.0_141664383_c0_r0

Contents

Prologue

T he war for america likely commenced early in the human history of the Americas. Indeed, it might have grown out of conflict already under way when the first East Asian hunters or fishers arrived in ice-age North America. This was no pleasure trip; the food-seekers almost certainly had been driven from home by enemies, or by hunger their enemies kept them from allaying. They knew life as a struggle: against nature for the resources required for human sustenance, and against other humans who stood in their way.

They were not individualists; singly they couldnt have survived the first winter. Their unit was the clan or the tribe, large enough to reproduce but small enough to relocate in response to setbacks and opportunities. To each tribe, other tribeslater arrivals from the old world, or splinters from the first comerswere competitors, presumptive enemies.

The enemies, while threatening the tribes from without, enforced coherence within. As generations passed, the tribes developed folkways that distinguished them from their enemies. The languages of different tribes grew mutually unintelligible. Their origin stories assigned to each tribe first place in creations plan. Strength and skill in defending the tribe in war against enemies became the hallmark of tribal leadership. The heroes of a tribe were its greatest warriors and became its leaders.

Alliances emerged, the better to wage war on non-allies. Weaker tribes were scattered, enslaved, absorbed. In a few spots, after the cultivation of food plants took hold, empires were built on the backs of tribes that couldnt get out of the way.

By then the climate had changed and the oceans risen, and the new world was cut off from the old. Memories of the old world had faded and died. Yet in the old world tribes competed and fought just as they did in the new world, just as humans always had. And when, after five hundred generations of separation, a few tribes from the old world discovered a novel route to the new, they joined the war they found in progress there.

PART I

The Making of the Warrior

1

I was born in No-doyohn Canyon, Arizona, June, 1829, Geronimo recalled from the distance of old age. In that country, which lies around the headwaters of the Gila River, I was reared. This range was our fatherland; among these mountains our wigwams were hidden; the scattered valleys contained our fields; the boundless prairies, stretching away on every side, were our pastures; the rocky caverns were our burying places.

Geronimos people, the Apaches, had not always lived near the Gila River. Their language was of the Athabaskan family, revealing roots far to the north, among the tribes of the Northwest Coast. The Apaches had migrated to the desert and mountains of the Southwest, probably under compulsion, for life was harder there. They reached the Gila River a few centuries before Geronimos birth, perhaps around the time Columbus reached the West Indies.

Geronimo was the fourth in a family of eight children. They were four boys and four girls. As a babe I rolled on the dirt floor of my fathers tepee, hung in my tsochcradleat my mothers back, or suspended from the bough of a tree, he said. I was warmed by the sun, rocked by the winds, and sheltered by the trees as other Indian babes. As he grew, he learned. My mother taught me the legends of our people; taught me of the sun and sky, the moon and stars, the clouds and storms. She also taught me to kneel and pray to UsenGodfor strength, health, wisdom, and protection. We never prayed against any person, but if we had aught against any individual we ourselves took vengeance. We were taught that Usen does not care for the petty quarrels of men.

Other lessons came from his father. My father had often told me of the brave deeds of our warriors, of the pleasures of the chase, and the glories of the warpath, Geronimo said. He and his brothers emulated what they heard. We played that we were warriors. We would practice stealing upon some object that represented an enemy, and in our childish imitation often perform the feats of war. Sometimes we would hide away from our mother to see if she could find us, and often when thus concealed go to sleep and perhaps remain hidden for many hours.

With age came responsibility. When we were old enough to be of real service, we went to the field with our parents not to play, but to toil. When the crops were to be planted we broke the ground with wooden hoes. We planted the corn in straight rows, the beans among the corn, and the melons and pumpkins in irregular order over the field. We cultivated these crops as there was need. Plots were modest in size. Our field usually contained about two acres of ground. The fields were never fenced. It was common for many families to cultivate land in the same valley and share the burden of protecting the growing crops from destruction by the ponies of the tribe, or by deer and other wild animals.

1

1