ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

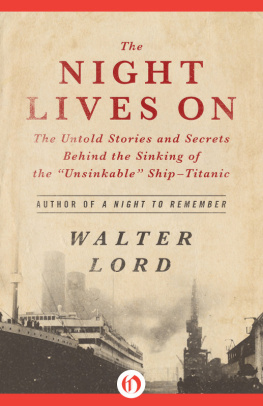

T hanks are due Walter Lord on three counts. First for suggesting that I edit Violet Jessop's manuscript; second for sharing the resources of his incomparable library; and third, for his generous suggestion to include two hitherto unpublished letters from his files (see following page and Appendix II).

Further thanks are due three of Violet Jessop's nieces: In London, Margaret and Mary Meehan supplied the original manuscript, photographs and marvelous first-hand remembrance of their lively aunt. From Canberra, Marilyn Skopal provided further illustrations and biographical documentation.

I am grateful to Ian Marshall for his invaluable guidance about the demise of HMS Audacious. Also from Maine, my old friend Norman Morse was helpful in providing specifics about turn-of-the-century Royal Mail tonnage. Californian Don Lynch offered extremely useful data about events aboard Titanic and Carpathia. For the cover illustration, I am indebted to Ken Marschall, arguably the foremost ocean liner artist of our time. Jack Eaton filled me in on the ongoing linkage between the White and Red Star Lines. From England, my cousin Robert Maxtone Graham was helpful with some background about the Voluntary Aid Detachment, Jessop's nursing organization. And I remain eternally grateful for Ed and Karen Kamuda's sterling work at the helm of the Titanic Historical Society. My warmest thanks to Lothar Simon of Sheridan House for his faith in my work and the privilege of being involved in bringing Violet Jessop's memoir before the public.

And always, final imperishable thanks to my dearest wife Mary who hears chapters before anyone else, who offers such wise counsel and without whom, this writer's life would be unsupportable.

John Maxtone-Graham

New York, January 1997

The following is an excerpt from a letter by Titanic stewardess May Sloan to her sister. Written on board Lapland en route from New York, it is a vivid account by another stewardess whose experience mirrors that of Violet Jessop.

S.S. Lapland, April 27th, 1912

My dear Maggie,

I expect you will be glad to hear from me once more and to know I am still in the land of the living. Did you manage to keep the news from Mother? We are now nearing England in the Lapland. I hope you got the cablegram all right.

I never lost my head once that dreadful night. When she struck at a quarter to twelve and the engines stopped I knew very well something was wrong. Dr. Simpson came and told me the mails were afloat. Things were pretty bad. He brought Miss Marsden and me into his room and gave us a little whiskey and water. He asked me if I was afraid, I replied I was not. He said: "Well spoken like a true Ulster girl." He had to hurry away to see if there was anyone hurt. I never saw him again.

I got a lifebelt and I went round my rooms to see if my passengers were all up and if they had lifebelts on. Poor Mr. Andrews came along, I read in his face all I wanted to know. He was a brave man. Mr. Andrews met his fate like a true hero realizing the great danger, and gave up his life to save the women and children of the Titanic. They will find it hard to replace him.

I got away from all the others and intended to go back to my room for some of my jewelry, but I had no time. I went on deck. I saw Captain Smith getting excited; passengers would not have noticed but I did. I knew then we were soon going. The distress signals were going every second. Then there was a big crush from behind me; at last they realized the danger, so I was pushed into a boat. I believe it was one of the last one to leave. We had scarcely got clear when she began sinking rapidly.

We were in the boats all night until the Carpathia picked us up, about seven in the morning. Mr. Lightoller paid me the compliment of saying I was a sailor.

Your loving sister,

May

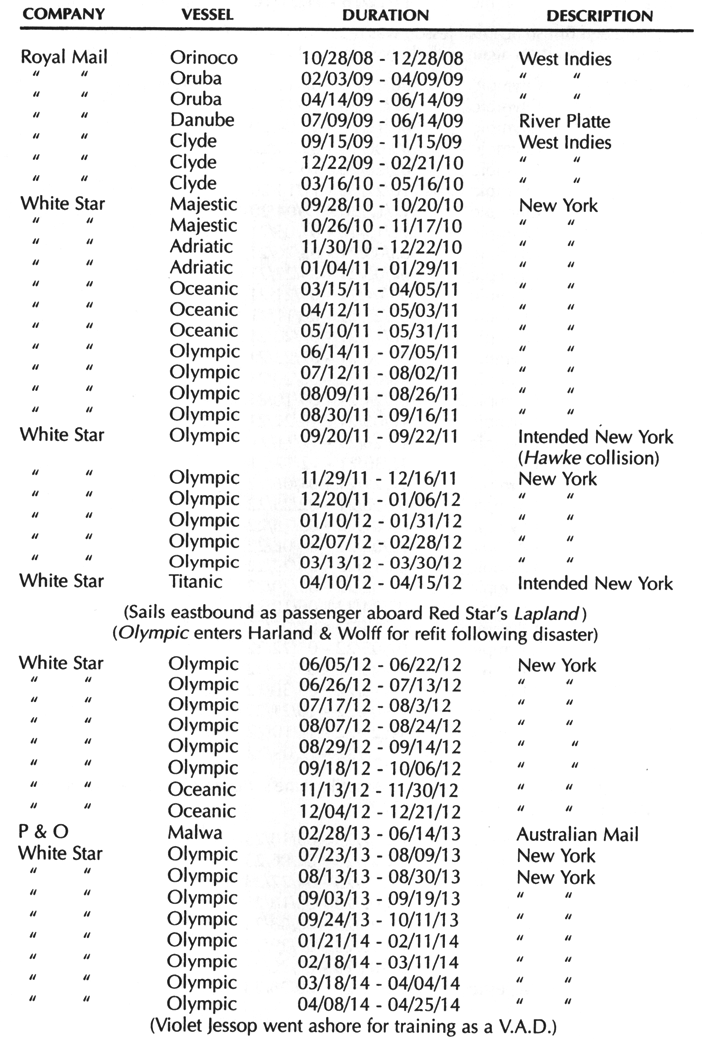

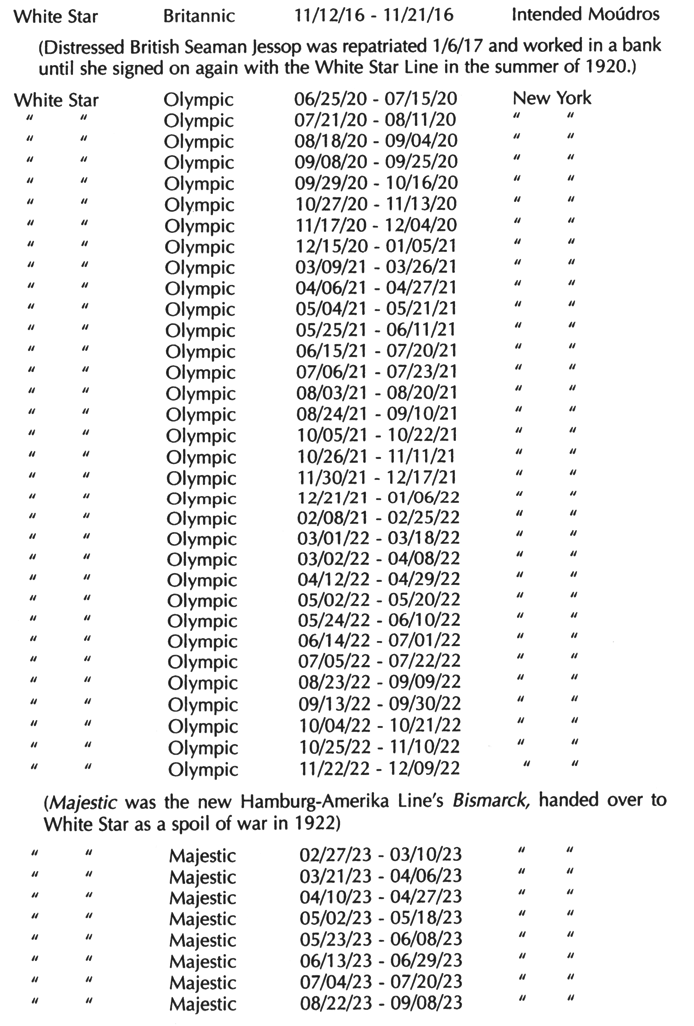

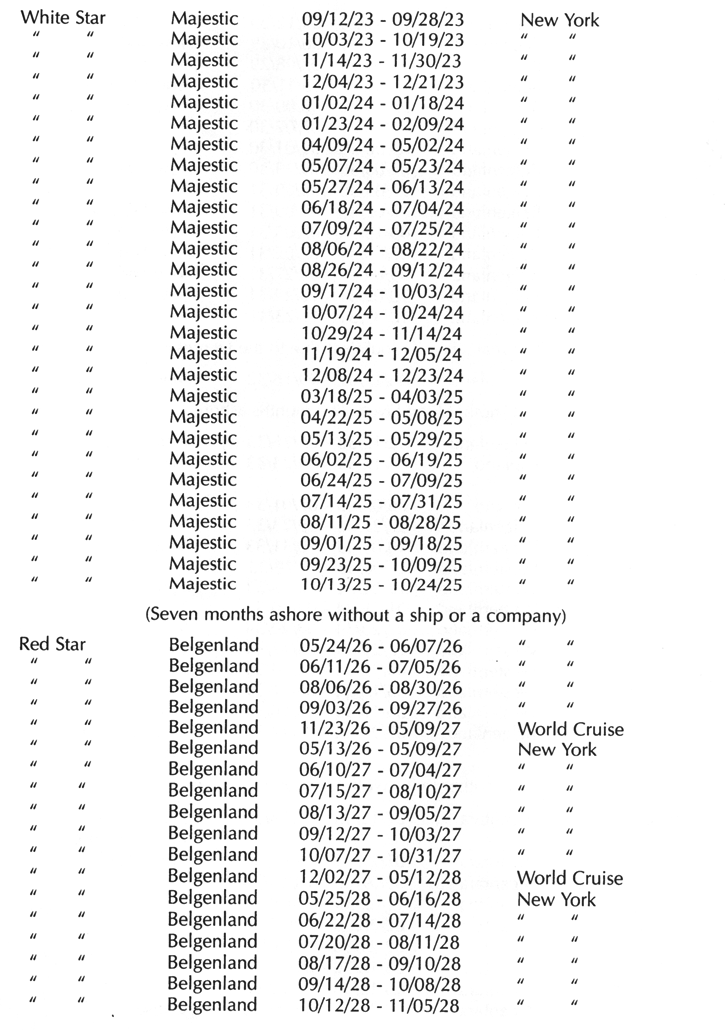

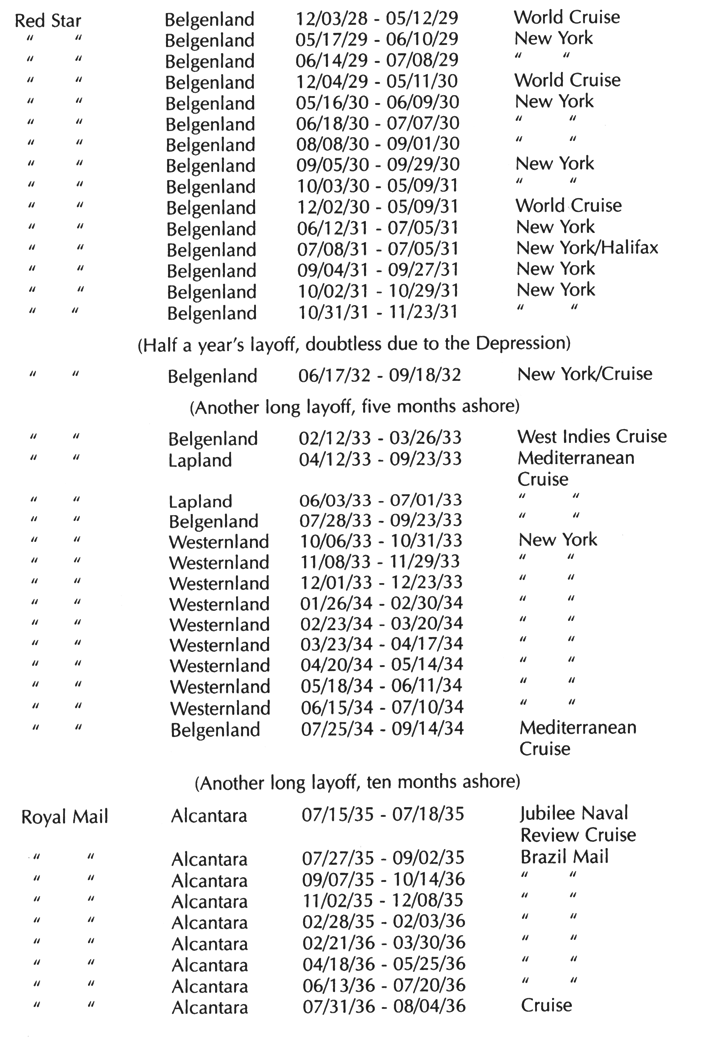

APPENDIX I

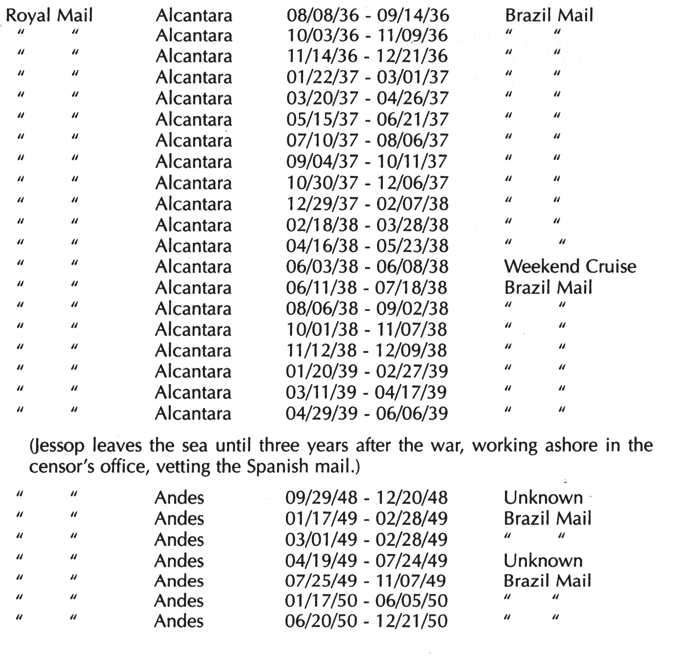

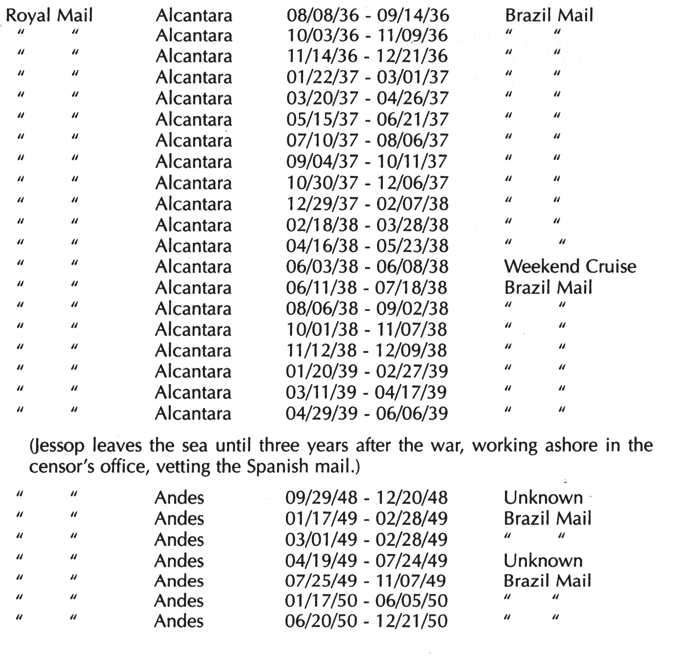

Jessop's Ships and Voyages

At the age of 63 years, just before Christmas of 1950, Violet Jessop signed off Andes and retired. She had pursued her career since 1908; forty-two years of life at sea, interrupted by two world wars and two shipwrecks, were over.

The foregoing has been compiled from Violet Jessop's four seaman's discharge books or, as each is labeled on the cover, Continuous Certificate of Discharge; representative pages are reproduced elsewhere. Those blue-bound volumes are about the size of a passport; on their pages, every British seaman's ship was documented and he or she was rated with a stamped VERY GOOD at voyage's end. (A voyage, in seamens' parlance, was a return trip, from home port outbound to destination and back again.) Not surprisingly, the pages of Violet Jessop's books are consistently festooned with VERY good's, one each concluding each of her more than 200 voyages.

In setting up the foregoing log, consecutive Olympic crossings or Alcantara journeys to Brazil could merely have been lumped together. But I think that listing every voyage separately conveys not only the extraordinary scope of Violet's sea time but also her complete life. In 1912 and 1916 respectively, she served only briefly aboard doomed Titanic and Britannic"New York and Modros Intended"and it is understandable that those notoriously incomplete voyages preoccupy us. But they skew the overall picture, shortchanging the bulk of a long career. We should be reminded of those other years of service where Violet Jessop performed with equal dedication. Reproducing the full log redresses that imbalance.

Violet tended to serve on vessels for long, continuous spells, including 60 not quite consecutive voyages on Olympic, 39 on Majestic, 38 on Belgenland and 29 aboard Alcantara. But regardless of which vessel she signed on, it was unquestionably a demanding life. Weekends and holidays were things of the past. From 1908 until 1913, for instance, she was at home in England for only one Christmas. Though they tended to be rougher, consecutive Atlantic crossings had the advantage of allowing more frequent time at home between voyages. When Olympic sailed westbound for New York, depending on the weather, about seventeen days would pass before she would tie up again in Southampton's Ocean Dock. Turnaround time there would vary, from as little as four days to a week, more than sufficient time for Violet to sign off and hasten up to London on the train to see her beloved mother and sister.

But when she transferred to the Red Star Line in 1926, Antwerp rather than Southampton became her home port. Voyages to New York on slower Belgenland consumed three and a half weeks. With only a four-day turnaround in Antwerp, there was time for no more than a hurried ferry ride across to England and back for brief visits between trips. But worse was in store: That immutable pendulum of Antwerp/New York service was interspersed annually with a world cruise, one each year from 1927 until 1931.