2015 by Stephen M. Hood

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording,

or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hood, John Bell, 1831-1879.

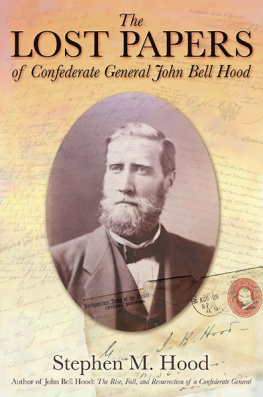

The lost papers of Confederate General John Bell Hood / edited and annotated by Stephen

M. Hood. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-1-61121-182-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

DIGITAL ISBN: 978-1-61121-183-2

1. Hood, John Bell, 1831-1879Correspondence. 2. United StatesHistoryCivil War,

1861-1865Personal narratives, Confederate. 3. United States--HistoryCivil War,

1861-1865Campaigns. 4. GeneralsConfederate States of AmericaCorrespondence. I.

Hood, Stephen M. II. Title.

E467.1.H58A4 2015

355.0092dc23

2014044563

05 04 03 02 01 5 4 3 2 1

First edition, first printing

Published by

Savas Beatie LLC

989 Governor Drive, Suite 102

El Dorado Hills, CA 95762

Phone: 916-941-6896

(E-mail) /

Savas Beatie titles are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by

corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more details, please contact Special

Sales, P.O. Box 4527, El Dorado Hills, CA 95762, e-mail us at , or visit

our website at www.savasbeatie.com for additional information.

Proudly published, printed, and warehoused in the United States of America.

To the only pure joys and loves of my life:

My wife Martha,

my sons Derek and Taylor,

and grandsons Harrison and Sam.

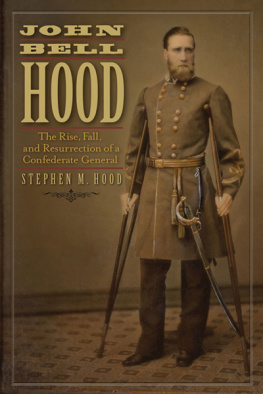

Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood (spring/summer 1862). Although his collar is that of a colonel, his buttons and sleeve are those of a brigadier. Applewhite-Clark Historical Collection: John Bell Hood Artifacts

Table of Contents

by Richard McMurry

List of Documents

Authors Note

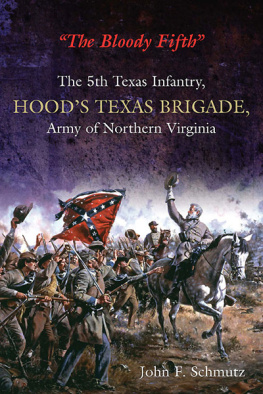

The title of this book is somewhat of a misnomer. The personal papers of Confederate General John Bell Hood were never really lost. Descendants of the Hood family were carefully watching over them. Carefully and meticulously stored, the cherished collection of more than 250 letters, certificates, photos, and ephemera was originally entrusted to one of John Bell and Anna Hoods orphans, who passed the papers to a siblings child, who in turn passed the important cache to the present custodian, a great grandchild of General Hood.

I was completing the research for my book John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General in 2012 when the holder of the papers (who wish to remain anonymous at this time) decided to share the existence of the papers to me. That decision made the invaluable historical information and insights into John Bell Hood the general, citizen, husband, father, and friend available to the academic and general reading world for the first time.

We owe to these three generations of descendants sincere gratitude for keeping safe the priceless information on one of American historys most fascinating characters.

Several letters included in this book were not among those contained in the collection of General Hoods personal papers. For the benefit of future researchers and historians, a few unpublished letters and photos owned by private collectors, including this author, are included in this volume and identified as such.

Finally, at the request of the family, three graphic anatomical descriptions (none of which bear on Hoods medical condition) found in Dr. John T. Darby report concerning Hoods Chickamauga wounding and recovery have been lightly edited for the sake of decorum. Otherwise, the reports are exactly as Dr. Darby wrote them.

Foreword

Growing up in the Atlanta area in the 1940s and 1950s I learned at a very early age that twenty-one evil and ruthless men bore all responsibility for every problemreal and imaginedthat beset the city. Nine of these malevolent fellows constituted a vicious gang that called itself the Birmingham Barons, and another nine formed an equally savage mob known as the Nashville Vols. Every summer these cretins slithered out of the slime-coated hovels where they spent most of their days and brought their baseball bats and gloves to Ponce de Leon Park. There they attempted to do unnatural and unpleasant things to our local heroes the Atlanta Crackers.

The nineteenth reprobate was Wally Butts, for many years the head football coach at the University of Georgia. Buttss teams did annual battle with the gallant Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets led by that chivalrous gentleman Coach Bobby Dodd. The twentieth bad guy was Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman whose plundering Yankee army captured Atlanta from the Confederates early in September 1864. In so doing the Federals forced Scarlett, Rhett, Prissy, Melanie, and Melanies baby to get in that wagon and flee the burning city.

The twenty-first evil man in the canonical saga of my native city was John Bell Hood.

In February 1864, following a three-year career as an outstanding (arguably the outstanding) regimental, brigade, and division commander in the Confederate army in Virginia, Hoodso the orthodox narrative went had schemed and flattered his way to a promotion to lieutenant general. This promotion brought with it Hoods assignment to command an infantry corps in the Rebel army defending Georgia.

Once he arrived in Georgia, the ambitious and unscrupulous Hood went to work to undermine the armys commander, the brilliant and beloved Gen. Joseph E. Johnston. Then, having played the major role in bringing about Johnstons July 1864 removal from command, Hood received his reward. President Jefferson Davis, a long-time enemy of Johnston, promoted Hood to full general and named him to replace his martyred predecessor. At the time he was relieved from command, the audacious Johnston was preparing to strike a mighty blow that would have shattered Shermans army and won Confederate independence.

Unfortunately for Southerners, Hood proved completely unsuited for the responsibilities of army command. Four times in July and August he clumsily lashed out at the Yankee army near Atlanta. In these utterly mismanaged battles, he hurled his troops against Shermans invulnerable fortifications, wrecked his army, sacrificed the lives of thousands of courageous soldiers whom the Confederacy could not afford to lose, committed one major blunder after another, and suffered defeat after defeat. Early in September, the hapless Hood abandoned the city to Shermans barbaric horde.

Then Hood took the little that remained of his devoted army off on what turned out to be a criminally irresponsible and almost comically mismanaged thrust into Middle Tennessee. There the army was all but destroyed. Once the pitiful remnants of the Rebel force had limped to safety in northern Mississippi, Hood resigned the command in disgrace.

In a final act of despicable and dishonest conduct, or so the story went, Hood spent the remaining years of his life in a desperate effort to dodge all responsibility for both his defeats and his heinous personal conduct. He blamed the failure of his plans on his predecessor as army commander, Joseph E. Johnston, and on his subordinates. Worst of all, he sought to cast blame for his own shortcomings and failures on the brave and devoted men of the army, so many of whom he had sent to slaughter.

As time went on, writers added even more drama to the woeful and sordid tale of Hoods life. That general, some of them asserted, became dependent upon drugs because of the pain he suffered from two serious wounds he had received in 1863, one of which had necessitated amputation of his right leg. Some maintained that his aggressive strategy and suicidal tactics drew their motivation from a desire to prove himself a man despite the loss of his leg. Several even speculated that Hood fought battles and went so far as to order soldiers to their deaths in a crude and bloody effort to impress his fiancee, the beautiful and coquettish Sarah Buchanan (Buck) Preston.

Next page

![Kyle J. Foley - John Bell Hood’s Division In The Battle Of Chickamauga: A Historical Analysis [Illustated Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/291124/thumbs/kyle-j-foley-john-bell-hood-s-division-in-the.jpg)