Contents

Guide

Contents

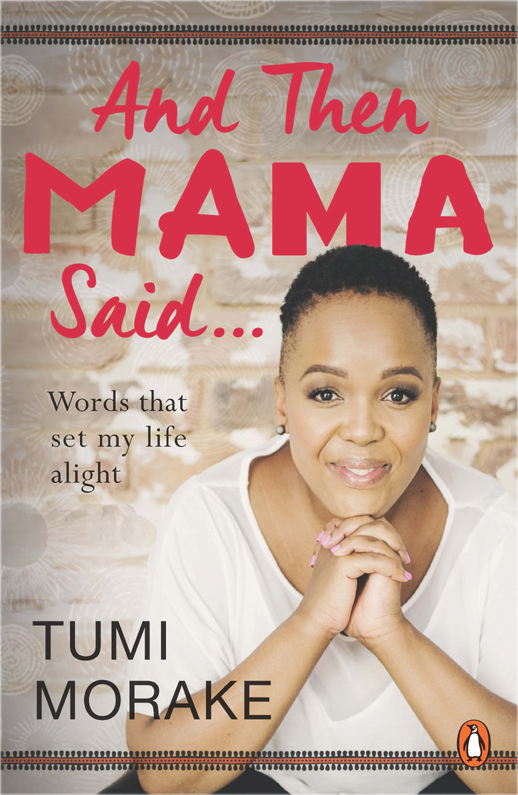

And Then Mama Said

Published by Penguin Books

an imprint of Penguin Random House South Africa (Pty) Ltd

Reg. No. 1953/000441/07

The Estuaries No. 4, Oxbow Crescent, Century Avenue, Century City, 7441

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa

www.penguinrandomhouse.co.za

First published 2018

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Publication Penguin Random House 2018

Text Tumi Morake

Cover image Kevin Mark Pass

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners.

PUBLISHER: | Marlene Fryer |

MANAGING EDITOR: | Ronel Richter-Herbert |

EDITOR: | Lauren Smith |

PROOFREADER: | Ronel Richter-Herbert |

COVER DESIGNER: | Monique Cleghorn |

TEXT DESIGNER: | Ryan Africa |

TYPESETTER: | Monique Cleghorn |

Set in 11.5 pt on 15 pt Adobe Garamond

ISBN 978 1 77609 334 2 (print)

ISBN 978 1 77609 335 9 (ePub)

DISCLAIMER

Every effort was made to credit the photographers whose photographs are included in this book. In cases where a name has been omitted or the original copyright holder could not be traced, we request that the relevant person contact us so that his or her name may be included in future reprints of this book.

I would like to thank Almighty God for this journey and opportunity. I have never walked alone through every trial and triumph there have been angels beside me, in human and ethereal form.

Mpho Osei-Tutu, my long-suffering husband, my rock. Thank you for taking over our mini musketeers and everything else I had to drop to get this book done. Mme Mahlape, my mother. In-law fell away long ago, I now use it purely for context. Thank you for reading this manuscript from day one, and for encouraging me when I became scared of my own voice. Ntate Tony, my cheerleader, thank you. Vonani, thank you for every call, every message, asking how the book was doing and whether it was done. You have no idea how that pushed me on my flattest days.

To my agents Osman and Shaaista, thank you for picking up my broken pieces and insisting I share my story. Lauren, editor extraordinaire, I hope you didnt lose any hair because of me. Thank you for your patience, insight and guidance. Penguin Random House, thank you for taking a chance on a voice that is often misunderstood, and being curious enough to risk an entire publishing deal on me. To every single person who sent me encouragement during my career and made me feel like I could have a story worth sharing, you too have had a hand in the birth of this book.

To Bonsu, Lesedi and Afia. I barely started writing about my life in this book; you will only find the bits that challenged, changed and grew me. I hope you grow up to be resilient and forgiving of yourselves. Thank you for allowing Mommy her absences and for showering me with so many hugs and kisses. Youve raised me more than you know.

Tebza, I hope I made you proud. You see, I am still a trier, moving with the confidence of a cockroach.

Dedicated to everyone brave enough to chase their dreams through treacherous waters. Keep swimming.

(I have a room at my mothers house)

When my mother faced challenges or felt like she had been painted into a corner, she would say, Ke na le kamore ko ga Mma. She was saying that as long as she had a home, she would survive. She also had a hand in building that home, and would tell me that to drill it into my head that you should invest in your family, in your home. That is how I was raised, by her and my grandmother: to value family and home above all else. Well, God came first, of course. That goes without saying.

Let me introduce myself properly: Ke Mokgwatlheng wa mmathari ga e tshwarwe e sena shokwe, o nthapelle ke sa robetse, fa ke eme ga ke sa na thapelo. That is our family totem greeting, which warns the listener to pray while I am sleeping, because once I am up, prayer isnt going to help them. Yup, thats me. Never catch me when Im alert. Your ancestors may find themselves negotiating with mine for mercy. In other words, do not take me on. Our clan is peaceful, but once you have wronged us, pray we make peace again or you will feel our wrath.

I am a Motswana girl, a thoroughbred, if that matters, who grew up on the dusty streets of Thaba Nchu in the Free State. I was born Relopile Boitumelo Morake. Relopile Boitumelo means we prayed for joy. When I see people smile or laugh in my presence, I feel I have lived up to that name. Relopile is a rare name; I have never met another. Boitumelo is as common as John; throw a stone and youll hit a thousand of us. I was born in Moroka Hospital in Thaba Nchu, where my mother worked. My upbringing was divided into three parts: I started out in a nuclear, white-picket-fence home in my early childhood, then was raised by my grandmother in my formative years. The last few years that needed adult supervision were taken over by the single parenting of Mama.

My father was a cop, but an underground ANC member. My mother was a nurse, also with political undertones. They were each highly intelligent, highly decorated firebrands. They met in the late 1970s in Thaba Nchu, when my father and a friend went to fetch a blanket my mother had borrowed. On the first visit they found my mother, but she had left the blanket elsewhere. On the second visit, my father went back by himself and left with the blanket and a phone number. Apparently it was love at first sight. Unbeknown to them, my dad was already a good friend of her sisters. He only discovered this when he went to see my mom, and there was my aunt. He asked her what she was doing there and discovered he had been dating his friends sister.

They got married and had one child, me. We moved to Taung while I was a baby, as my father had been transferred to a police station there. I was far too young to have memories of the time we lived in Taung, but I remember we stayed in the police barracks of the Imperial Reserve when we moved to Mafikeng in my toddler years. My memories of life with my parents as a married couple are sporadic. They used to host small parties from December to January to celebrate our birthdays. First up was Mama, on 21 December, followed by me on 22 December, then my dad on 2 January. We used to hang out in the back garden, on the veranda overlooking the mulberry and apricot trees.

I played by myself a lot, letting my imagination run wild. I would often refuse to go to bed alone, however, and they would take me to their bedroom and let me fall asleep there before carrying me to my room. My eldest half-sister, Disebo, lived with us when she was in high school and I was in nursery school. I recall a lot of breakfasts with everyone around a little square table, Mama in her starched, pure-white nurses uniform with maroon epaulettes, and Dad in his green cop uniform and hat. Most of my memories of Disebo take place in the mornings, perhaps because she was a teenager, so I saw very little of her. She and my mother clashed as well, so her living arrangement with us did not last long. Interestingly enough, though, they became close when Disebo was an adult. In fact, my mother ended up having a better relationship with Disebo than the one I have with my sister even now.