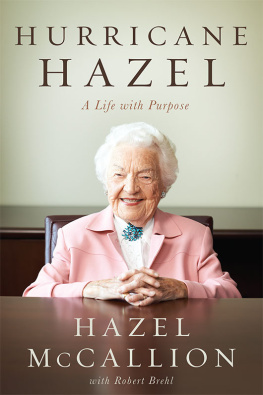

It was October 1954, and a long work week was over. Among the projects I was juggling was leading a team in building a facility in Alberta that would be the first to experiment with extracting oil from the tar sands. My political life was more than a decade away.

I was employed in the private sector for an engineering company called Kellogg Canada Co. Ltd., a firm that had had many successes. Perhaps most notable for Kelloggand for me personallywas that it built Canadas first synthetic rubber plant in Sarnia, Ontario, during World War II when rubber supplies dried up for the Allies as the Japanese military swept across the Far East.

After the war, Kellogg was building power plants and oil refineriesimportant things to help Canada grow in the postwar years. Though the hours were long, it was exciting work. The economy was booming and we were building and looking ahead. Always building.

There was nothing especially memorable about this particular work week, but the weekend would most definitely be extraordinary. It was a time I will never forget, and no one else who was there then will either. Little did I know that this event would also be linked to me throughout my career.

After work on Friday, October 15, 1954, I locked up the Kellogg office at the intersection of Yonge and Bloor streets in Toronto and waited for my husband, Sam, to pick me up for the drive home.

Having married three years earlier, Sam and I both worked in Toronto, but we lived in a picturesque town twenty miles (30 km) northwest of the city, called Streetsville. My job was office manager at Canadian Kellogg, and Sam worked in production at Canada Ink; both companies have long since disappeared. Although today the roads and highways around the Greater Toronto Area are choked with hundreds of thousands of cars, back in 1954 it was not common to commute so far between home and work. With money tight, we often carpooled with another couple named the Bishops, who also lived in Streetsville.

As I got into the car, I noticed how dark it was and how the wind was picking up. There was rain, but it was certainly not a driving rain. We headed west and drove out along Dundas Street. As we made our way through the city, I noticed the branches of trees swaying and leaves blowing across lawns and onto the road. The four of us talked with the swish of the windshield wipers in the background. I dont remember being particularly concerned by this storm as we drove. We all needed groceries, so we stopped at the Dixie Plaza to shop. Though we were only about halfway home, this was the most convenient place for groceries. Unlike today with supermarkets in abundance across urban centres, there were few back then in what was mostly farmland in Toronto Township, as it was called. If wed had any real concern about the storm, I am sure we would have continued straight on home. Our one-year-old son, Peter, was there with our nanny and we would have rushed to get to him if wed thought there was any danger.

Our groceries bagged, we went out to the car and felt that the wind was noticeably stronger. We continued along Dundas and turned right on Mississauga Road to head north to Streetsville. A short while later, Sam slammed on the brakes because trees were down and blocking the road. This was around where the campus of University of Toronto at Mississauga (UTM) now sits. Sam turned the car around and headed back to Dundas. We jigged around and found a north-south township line that was clear of debris and we successfully made our way home. I turned the radio on and it sounded as if we were in for some rain and wind, but I still didnt get the impression there was any danger. I dont recall anyone on the radio issuing any warnings or emergency procedure orders.

Sam and I had dinner, played with our baby and hunkered down for the night. I could hear the rain and the wind whipping outside, but the three of us were warm and dry in our house, located on high ground not far from the Credit River.

The next morning, it was still raining, but not nearly as windy. Sam had promised his mother that he would bring the baby to her in Torontos west end for a visit. After breakfast, they headed out to the car and off they went.

Like working mothers today, I tried to catch up on my housework on Saturday mornings. In the kitchen, I turned on the radio and got the shock of my life. Bridges were out or said to be unsafe. Homes were destroyed. Lives were lost. Hurricane Hazel had struck Toronto overnight with all its force, but thankfully we were spared the brunt of it in Streetsville, although one bridge was damaged beyond repair and had to be replaced.

After listening to the first radio report, I ran to the door to try to catch Sam, but the car was gone. There was no way to reach him. Fear set in as the man on the radio talked about this bridge or that bridge being washed out and police urging people to stay away from all bridges and rivers.

I phoned Sams mother. She was fine and, like me, somewhat in the dark about the storm. Now she was worried, too, but what could I do? This was long before cellphones, and there was no way to reach Sam in the car. In timeit felt like hours, but it was only minutesSam called to let me know he and the baby were safe, and that the drive in wasnt all that adventurous. He later took the same route home and returned safely without incident.

Looking back, I often wonder why we werent more worried that night. But years later I read the final official forecast of the storm from the Dominion Weather Office. It was issued at 9:30 p.m. on October 15, 1954. It reads:

The intensity of this storm has decreased to the point where it should no longer be classified as a hurricane. This weakening storm will continue northward, passing east of Toronto before midnight. The main rainfall associated with it should end shortly thereafter, with occasional light rain occurring throughout the night. Winds will increase slightly to 45 to 50 mph [72 to 80 km/h] until midnight, then slowly decrease throughout the remainder of the night.

Someone at the weather office failed to do his homework. Or maybe it was simply Mother Nature telling us who is boss.

Instead of dissipating, Hurricane Hazel pounded Southern Ontario throughout the night with the fury of winds of sixty-eight miles per hour (110 km/h) and dumped almost a foot (300 mm) of rain on the Toronto region. Thousands of people were left homeless as torrents of water hurled through flood plains heading to Lake Ontario, taking homes, cars, trailers, anything in the path of the water.

All told, eighty-one people died around Torontoalmost as many as the hundred deaths in the United States, despite the hurricane having hit land with full force in North Carolina, where youd think it would have been strongest, and making its way through Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania and New York. Could some of these Canadian deaths have been prevented had the hurricane been treated like the emergency it was? Would people have evacuated homes located in flood plains before surging storm water tore them apart?