New York London

Copyright 2015 by Tat Wood and Dorothy Ail

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to Permissions c/o Quercus Publishing Inc., 31 West 57th Street, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10019, or to .

e-ISBN 978-1-62365-486-3

Distributed in the United States and Canada by

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

www.quercus.com

Introduction

In selecting 200 short pieces to represent everything people have done we had to impose strict criteria. Did this incident, trend, nation or person have a knockon effect? Is it what a casual reader, picking up a book like this, wants to find out about in a hurry? Anything in this book is either something that has passed into public consciousness (maybe without most people knowing why was Ivan IV of Russia really so terrible?) or is there to explain how we got from there to here.

We argued across the Atlantic about what should go in and why. Most of these pieces are encounters between one culture and another. For most of history those encounters are either military or commercial or both but some are about how ideas spread. We sought to punctuate terse accounts of massacres with more positive underlying trends.

Any one of these topics deserves a book-length discussion but this will get anyone interested started. We had to omit many pet subjects Sabbatai Tsevi, the Lost City of Zimbabwe, the Franco-Prussian War, Prohibition, the invention of the novel. It becomes more Eurocentric as we come closer to today simply because the main story of the past five centuries involves Europeans at first treating other places as theirs, and later being asked to leave.

This book can only hope to offer a starting-point, although we hope its comprehensive enough for everyday domestic use and will inspire further investigation elsewhere.

Tat Wood and Dorothy Ail

Lucy and her kin

One of the most famous fossils ever discovered, Lucy is the skeletal remains of an Australopithecus afarensis. Found in Ethiopia in 1974, she lived around 3.2 million years ago and was a bipedal hominid, with feet adapted for walking upright.

The history of human evolution extends both forwards and backwards from this point. Hominidae, the taxonomic family that humans share with their closest living relatives, the great apes (gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans and bonobos, the last controversially suggested to be closer to Lucy than modern humans) shared a common ancestry until quite recently in evolutionary terms, perhaps differentiating 6 million years or so ago. The first beings to walk upright comfortably seem to have been the Australopithecus genus, developing around 4 million years ago; they had smaller brains than even modern apes, and became extinct perhaps 2 million years ago. But they were able to develop tools, and genus Homo (which includes modern humans) evolved from them.

Skull of Mrs Ples, the most complete australopithecine fossil so far discovered.

Tools, art and belief

While many animals have learned to manipulate objects such as twigs to release food from inaccessible places, humans are the clearest example of what psychologists call theory of mind. Early art indicates that this is as old as humanity depictions of people and events are physical manifestations of mental processes, made to look recognizable to others, and with this came other significant abilities.

One is that an individual can imagine what another individual might do; verbal communication can go beyond information and orders into storytelling and attempts to guess anothers reactions: associated regions of the brain developed rapidly in this period (some have suggested that civilization began with the ability to gossip). Another is that complex and abstract notions can be relayed, including plans for hunts or future projects things that cannot be seen. A third consequence is a realization that this ability ends when an individual dies: surprisingly early, we find humans buried with personal objects.

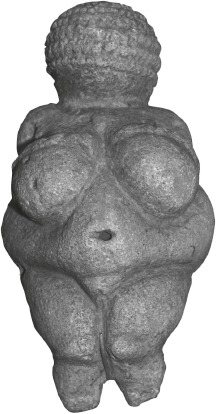

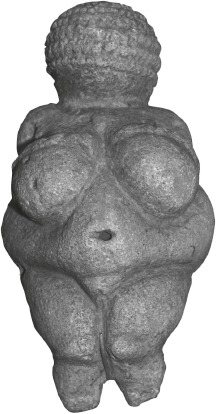

The Venus of Willendorf is one of the most famous examples of prehistoric sculpture, dating to around 26,000 BC.

Out of Africa

The genus Homo evolved in Africa a little less than 2.5 million years ago, characterized by increasingly large brains that equipped them better for survival their predecessors the australopithecines became extinct soon thereafter. Mary and Louis Leakey became famous for their discovery of the Homo habilis site in Tanzanias Olduvai Gorge a small ape-like biped that was skilled with stone tools (hence the name). Later hominids were larger, stronger and more anthropomorphic.

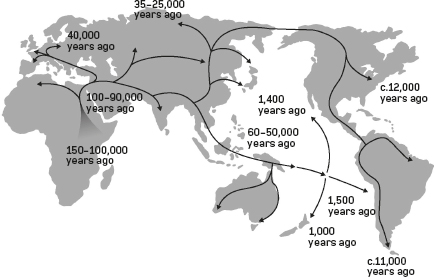

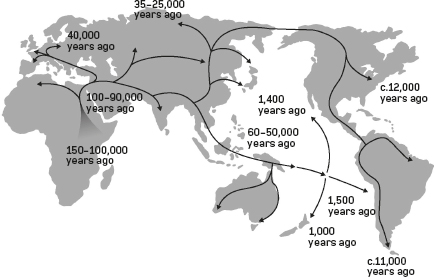

The fossil record shows that hominids spread from Africa to Europe and Asia in multiple waves beginning about 2 million years ago (exactly how many species were involved, and how recently some survived, remains uncertain). They appear to have developed vocalization, hunter-gatherer social groups and the use of fire over the next million years. The current scientific consensus, supported by DNA studies, is that modern humans arose in Africa 200,000 years ago, before spreading out, replacing and interbreeding with other hominids.

This map shows the spread of modern Homo sapiens out of Africa with approximate times of arrival other hominid species had made similar journeys long before.

Neanderthals

Homo neanderthalensiss close affinity to modern humans and European stronghold meant that it was the first fossil hominid to attract attention (discovered in Germanys Neander valley in 1857). The Neanderthals seem to have settled after the first wave of hominid migration from Africa and to have persisted until about 40,000 years ago. Homo sapiens, meanwhile, may have arrived from Africa 60,000 years ago, so could have played a major role in Neanderthal extinction. DNA evidence for interbreeding is as yet inconclusive.

Scientists originally surmised that Neanderthals were unintelligent, hunchbacked beings, largely because one of the first skeletons found was of an arthritic man. More recent finds have shown that they were physically powerful, and evidence is increasing of abstract reasoning and large cerebral capacity. Physically capable of limited speech, they had sophisticated flint tools and religious rites many burial sites have been found.

Next page