| Sonic Youth Slept On My Floor: Music, Manchester, and More: A Memoir |

| Dave Haslam |

| Little, Brown Book Group (2018) |

|

Published by Constable

ISBN: 978-1-47212-750-1

Copyright Dave Haslam, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Constable

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.littlebrown.co.uk

www.hachette.co.uk

To my parents, with love and gratitude.

Contents

Fear not for the future, weep not for the past

Percy Bysshe Shelley, poet

Be normal / Be unusual

Pete Shelley, poet

A former Poet Laureate, Andrew Motion, wrote that what he enjoys most in a biography is information about ordinary matters, such as haircuts. I have all the encouragement I need. Already Im thinking about one particular haircut, and the circumstances surrounding it.

It was the mid-1980s. I was in my early twenties, with a deep desire to meet interesting people, especially musicians, artists, writers. Id been bewitched by the world of great music and electrifying ideas since my early teens.

I had started a fanzine called Debris. From the late 1970s to the mid-1980s, there were hundreds of fanzines: small, independent magazines, usually photocopied on A4 or A5, in which writers often just one person, an enthusiast and an early adopter, or a small crew would evangelise about music that wasnt widely appreciated.

I had a little gang of mates, but I didnt know anyone in the media; there was never an option to write for a proper magazine. I didnt know who to phone. I carried with me a plastic bag full of cassettes, and a heart full of dreams.

I was floundering a little, but I expected one day not to be. I was under the impression that somehow, as you got older, things became easier; youd feel comfortable in your skin, untroubled by anxiety. I expected to find a map of where to find happiness. Ask me now, and Ill tell you: there is no map. But I always had music through the good times and the bad. I understand this from Maya Angelou: Music was my refuge. I could crawl into the space between the notes and curl my back to loneliness.

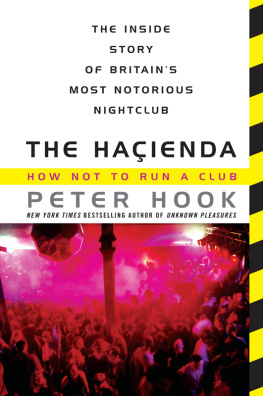

In 1985, I was a regular customer at the Haienda, a club in Manchester that had been opened by Factory Records and New Order three years earlier and featured mostly, but not only, live music. In the early years, some gigs were busy and there was sometimes a queue, but many events, including a Club Zoo night featuring a secret Teardrop Explodes appearance, were attended by just a few dozen people.

I was queuing outside the club once it was a night Cabaret Voltaire were playing and I saw NME journalist Paul Morley walk to the front of the queue. He had a confident stride, a long coat and a lovely, striking girl on his arm. It was Claudia Brcken from the group Propaganda; I think Paul and Claudia were engaged to be married at the time.

Prior to the opening of the Haienda, the prevailing look of British nightclubs and discotheques included swirly-patterned, cigarette-singed and drink-sodden carpets, and a desperate and usually not very well-executed attempt at glitz involving yards of chrome and maybe a few plastic palm trees.

Factory called on the services of Ben Kelly, who had designed the facade of the Seditionaries shop for Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren. His Haienda design made a feature of the ex-warehouses look. There were no carpets and no attempt at glitz.

Inspiration for the Haienda came from the look and concept of New York venues like Danceteria and the Mudd Club. Tony Wilson, the co-founder of Factory Records, explained the club would be a videotech and two large screens were installed either side of the stage. The video operator in the early days was Claude Bessy. Claude spliced, cut up and compiled idiosyncratic film montages, all on slightly wobbly VHS. These were projected onto the screens. He favoured shots of dancing girls, Nazi rallies and air disasters, and clips from films by the likes of Luis Buuel and Kenneth Anger. It was the least MTV-ish video selection imaginable.

Id be in the Haienda to see the bands but also often to sell the fanzine. I took a pile of them out most nights. Id walk around venues badgering the crowd at gigs by the likes of Orange Juice, the Fall and the Smiths, and start by trying to sell them to the queue. A few people would regularly volunteer to help me. There were a couple of girls who used to sell loads of them: Carol Morley, who went on to become an award-winning filmmaker, and Janet, who became a sex therapist.

Andrew Berry ran a hairdressing salon called Swing on weekdays in the basement of the Haienda. His haircutting business wasnt a nine-to-five operation; he would close Swing for the day, on a whim, or turn up three hours late. You wouldnt expect to make an appointment. Friends of Andrews such as Johnny Marr would drop by for a haircut. Genesis P-Orridge from the group Psychic TV was a visitor. Multiple conversations would ensue. You willingly gave up half your day if you wanted a haircut at Swing.

A guy called Neil worked alongside Andrew, and two girls were employed too: Tracey and Heather. Swing would advertise in Debris, but Andrews adverts were curious. He wanted me to put in a big photo of Charles Manson with Hair by Swing as the strapline. I wasnt 100 per cent sure Charlie Manson was the right person to represent Andrews salon. It wasnt just that he was a nutcase and a murderer but also Mansons hair was a mess. Andrew backed down and said hed come up with a new idea. The next day, he gave me a picture of William Shatner playing Captain Kirk, which he had doctored by drawing a swastika on Shatners face. As a piece of PR I wasnt convinced that this was an improvement, but I needed that 40 for the full-page ad.

Andrew and his Swing contingent werent the only people I knew who worked at the Haienda in the early days. Susan Ferguson, my housemate and best mate, worked behind the bar. I knew Sue because wed been to school together in Birmingham and then both moved up to study at the University of Manchester in 1980. She got a job at the Haienda two years before I got a regular DJ job there. She was far more sociable than me, had a fantastic smile, and lots of people would take a shine to her. We had a hundred mutual interests and we looked after each other.

The first time I met Mark E. Smith, I was introduced to him as a friend of Sue Fergusons and it was the same when I met Terry Hall. She particularly enjoyed the shifts she worked alongside Glen and Brendan in the Haiendas cocktail bar the Gay Traitor, as it was called. Id be bored some evenings and get the bus into town and take Sue a snack or a gift. I remember one time being stopped at the door and having to explain my mission to one of the doormen. Its Dave from Debris, I explained. Ive come to bring a banana to one of your staff. I showed him the banana. He let me in.

In addition to cutting hair, Andrew was also a DJ. He used to DJ at the Haienda, usually under the name Marc Berry; hed be employed to play records before and after bands, and Id go stand with him in the DJ box to watch the bands. Overlooking the dancefloor, and with a great view of the stage, the DJ box was only accessible from a corridor running from the back of the balcony down to the main bar. Next door was another wooden box, where the lighting boys sat, and thats also where the videos were operated from. The door into the DJ box was similar to the kind you might find in a stable; the top half could be opened (inwards) but you could lock the bottom half of the door. (The DJ box will be the site of several episodes later in this book, including one featuring a naked girl and another featuring a man with a gun.)