All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

Overland travel is a great deal more trouble and very slow, but it is uncomfortable in a way that is completely human and often reassuring. A book like this, or any book I have written, is not a problem to study and annotate. It is something I wrote to give pleasure; it is something to enjoy. You should be able to see these people and places, to hear them and smell them. Of course, some of it is painful, but travelits very motionought to suggest hope. Despair is the armchair; it is indifference and glazed, incurious eyes. I think travelers are essentially optimists, or else they would never go anywhere; and a travel book ought to reflect that same general optimism.

Note to the Reader

I ve been called gringo dozens of times. My first day in Latin America I stepped out of the airport in Guatemala City and baggage handlers, taxi drivers, money changers, and beggars greeted me with a cacophony of oye gringo, mira gringo, vamos gringo, compra dolares gringo, aydame gringo, yo te llevo gringo, buen precio para mi amigo gringo. I was scared, overwhelmed, and I didnt speak enough Spanish to understand much more than Listen up, gringo. I also wasnt sure how to interpret my new nickname: was it offensive, racist, disrespectful? Over the years gringo became a second name but rarely employed with malice or ill will. There was the occasional gringo de mierda, pinche gringo, or gringo culiado, but much more common was the neutral oye gringo, or the warm gringito, or the sweet mi amigo gringo. Since the word was generally used as a friendly nickname when people didnt know, or couldnt pronounce, my nameand I cant really blame them for thatI decided that it didnt bother me. Usage was key.

I heard plenty of theories about the word gringo: Mexicans yelled at Yankee troops in green uniforms during the battle of the Alamo to go home, green-go; during the Mexican-American War beginning in 1846, the troops invading Mexico sang a song called green grow the lilacs and the Mexicans who heard them started calling them the green grows; a United States citizen with the last name Green was in charge of administering a huge banana plantation in Central America and during a labor protest the workers started chanting Green go home! But none of those seems likely given how geographically limited they werethe word gringo is used most everywhere Spanish is spokenand the fact that the United States Army didnt start wearing green uniforms until decades after the Alamo and the Mexican-American War.

The word gringo first appeared in Spanish dictionaries in the late 1700s and was defined as a word used to describe foreigners who had difficulty speaking the language. This version suggests that the word is a bastardization of the Spanish word for Greek, griego, as in its all Greek to me. It might be that the Mexican-American War coincided with a shift in usage of the word to mean English-speaking foreigners in particular and perhaps a negative connotation as well.

Semantics aside, I have been a gringo, for better or worse, going on ten years. Between 1999 and 2008, I was itinerant. I visited seven continents and more than eighty countries and slept on hundreds of couches and sandy beaches. But I concentrated most of my travel time in Latin America, where the languages, landscapes, and politics (not to mention the fried sweet plantains that I devoured every chance I got) captivated me from day one. Over the years, I traveled in search of adventure, to learn a bit about the planet, and to find myself.

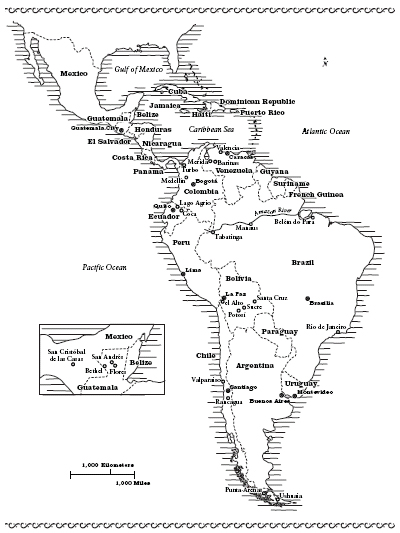

Being on the road, traveling the earth, testing myself against a constantly changing backdrop became addictive. Settling down in one place for more than a week seemed undesirable, impossible even. I built a network of friends and responsibilities that spanned the continents and kept me on the move. I resisted certain commitmentsless in terms of relationships or work or responsibility and more in terms of anything that would require me to be in one place for an extended period of timein a way that made it hard to build a stable life. Months in advance, I accepted short-term obligations in random, far-flung parts of the globe that prevented me from staying put. As my Spanish and Portuguese slowly improved I found travel in Latin America more rewarding. In Rwanda or China I had limited communication and, as a result, my ability to understand and access the people, politics, and places was more restricted: language was either a great wall separating me from people and places or a skeleton key opening every door. Drawn back to Latin America again and again, I ended up exploring virtually every country in the region. Of course, I concentrated my time in some countries, and in those places built more intimate relationships with people, politics, and geography than I was able to in others.

My personal journey was set against a constantly changing political backdrop. As I grew and changed, so did the region. I was born into a North American family with anti-imperialist politics at the dinner table and in their blood, but many of my conscious formative personal experiences took place in Latin America. During the decade that I explored myself and the region, Latin America was in the process of making a significant political shift. This book then has two narrative threads: my personal journey, and the places I was passing through. Weaving them together on the page was more challenging than it was in real life. The written word has a unique sort of permanence. In life I can do something one way today and another tomorrow. I can recognize my current perspective and understanding as inherently limited, flawed, and subject to change. Conveying that sense of change, that possibility for evolution in a project that is necessarily finite, sometimes eluded me. The risks of dogma, ideology, and partisanship become all the more perilous on the printed page.

In the chapters that follow, I write about the countries that resonated most with me personally; they are also representative of the regions shifting politics. Cuba, Mexico, and Nicaragua are notably absent from this book. Ive visited all three but those stories will have to wait for another time.

The places I focus on are those that offered meaningful lessons, often from personal, on-the-ground experiences. Many of the people I met and profile here are smarter, more open-minded, and richer in life experiences than I am. I was glad to be an observer ofand sometimes participant intheir lives, struggles, and conversations. I hope my accounts of them, even through what are inevitably partial sketches, provide a window into this dynamic, fascinating region.