Contents

Guide

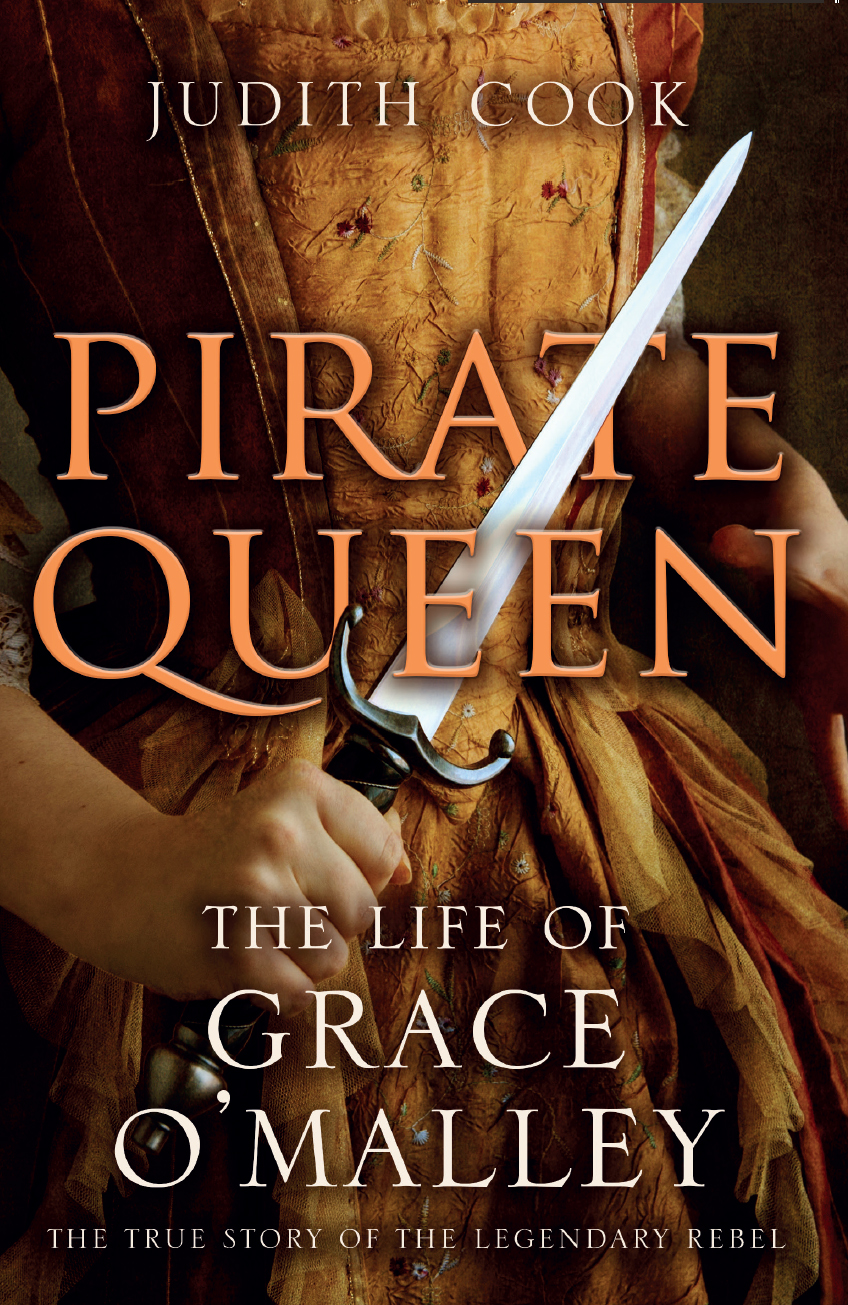

Well-known as a Guardian columnist and as an anti-nuclear campaigner (she founded the organisation Voice of Women after the Cuban missile crisis of 1962), Judith Cook was also a prolific biographer and investigative journalist. Her subjects included J.B. Priestley, Daphne du Maurier and Hilda Murrell, the anti-nuclear campaigner who died in mysterious circumstances in 1985. Born in Manchester, Judith Cook lived for many years in Cornwall, where she died in 2004.

The meeting of Grace OMalley and Elizabeth I from Anthologia Hibernica (VTR/Alamy Stock Photo)

For Daisy

This edition published in 2021 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2004 by Tuckwell Press Ltd

Copyright the Estate of Judith Cook 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permis-sion of the publisher

ISBN 978 1 78027 715 8

ePUB ISBN 978 0 85790 311 2

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Polmont, Stirlingshire Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Contents

Map

Acknowledgements

As ever, a project like this would be impossible without the help and advice of libraries. My thanks therefore to the staff of the Bodleian Library, the British Library, the Public Record Office, Trinity College, Dublin and the Morrab Library in Penzance which now has its own Celtic Studies section. The various librarians were not only sympathetic when I used their facilities but were extremely helpful in answering my e-mails and making suggestions as to what was available. Also to the very useful bibliography of State Papers (Domestic) and the State Papers of Ireland researched by Anne Chambers for her own book, Granuaille, and for the assistance of the Galway Tourist Board. Last but not least, my thanks to Val and John Tuckwell who made the project possible.

Judith Cook

Introduction

The year is 1586. The place Ireland. Her arms pinioned behind her, a woman stands on a brand-new scaffold especially erected in her honour. Triumphantly organising the show is Sir Richard Bingham, English Governor of Connaught, a man notorious for his brutal treatment of the population and for the savagery with which he puts down insurrections; he has recently hanged a number of hostages as a reprisal for an uprising. He is feeling very pleased with himself for the woman was lured into the trap he had set for her by being offered letters of safe conduct which he subsequently failed to honour. He has no compunction about executing a female prisoner since he considers her to be the most notorious woman on all the western coasts, a notable traitress and the nurse of all rebellions in the province for forty years. She is to be hanged as a warning to others.

The woman in question is Grace OMalley, variously nicknamed Grainne, Grainemhaoil or Grania OMalley. Though she has been married twice, OMalley is the name by which she is always known and which she has made almost as notorious as that of Bingham, though in a very different way. She is now in her mid-fifties but remains a striking figure. Among the charges levelled against her, apart from rebelling against the English Crown, is that she had been planning to bring in more Scots mercenaries, the galloglas, to assist in the latest campaign against the English. She has a reputation for the drawing in of Scots, a practice of which the English administration takes a particularly dim view.

One report has it that the rope was actually around Graces neck when, as the assembled onlookers watched in silence, the sound of a galloping horse was heard and into the crowd rode a messenger from England demanding her immediate release on the orders of Queen Elizabeth herself. Whether or not matters had actually got quite so far, there is no doubt that the planned execution was stopped. Bingham had no alternative but to return her to prison before finally, and reluctantly, releasing her into the safekeeping of her son-in-law, Richard Bourke, known as the Devils Hook, who he rightly rated as little more trustworthy than Grace. Within no time Bourke had joined the rebels and Grace had immediately set about contacting the Scots, arranging to ferry them in using her own fleet of galleys.

But the lead-up to what sounds like a scene from a film or television costume drama had been a long one. Graces previous career had already spanned trading to the Iberian peninsula and the Mediterranean ports, two marriages, an earlier spell in Dublin Gaol and, most notably, the activity at which she was most successful and for which she had become best known: piracy. She was also a noted gambler, could play at politics and was possibly a part time intelligencer for Elizabeths spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham, when it suited her. Today they call her the Pirate Queen.

Yet for a very long time after her death, no mention is made of her in any of the histories of Ireland, not even the Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters, although there is no shortage of myths and legends, some of which might well be true or at least based on fact. Others, though, have to be treated in a similar way to the apocryphal exploits of Robin Hood or Rob Roy, and for much the same reason. Like them she achieved the reputation of a flamboyant, dashing outlaw to whom such stories naturally accrue with the added spice that in this case it is a woman, not a man, who takes the starring role. However, the attitude of the much later nineteenth-century historians towards her is still distinctly odd. For in some she merits at best only a few lines, and then in connection with one or other of her admittedly colourful husbands, or because she famously publicised the plight of the widows of sixteenth-century Ireland who were legally unable to inherit land. Yet she was a major player in the Ireland of her day. Therefore for accurate, and accurately dated, contemporary information about her various activities, her political involvements and the threat she was thought to pose to the English government, we have to turn to the Calendars of State Papers (Domestic) of the period, the State Papers of Ireland and various reports appearing in the papers of, among others, the Sidney and Salisbury families.

One explanation for the neglect of the predominantly male historians might simply be her gender: she was a woman very much out of place in the mans world of warfare and politics, her behaviour quite outside the boundary of what was considered acceptable even though she lived through an era which saw two Queens on the throne, Elizabeth in England and Mary Stewart in Scotland. But on the whole, although there are legendary exceptions, the Ireland of her day, and later, preferred its women as suffering heroines, preferably