CONTENTS

Guide

The Woman Who Scandalized Eighteenth-Century London

The Duchess Countess

Catherine Ostler

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2021 by Catherine Ostler

Originally published in Great Britain in 2021 by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Atria Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Atria Books hardcover edition November 2021

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Jacket design by Alan Dingman

Jacket art by Jakob BjrkEleonora Gustafa Bonde af BJrn

Author photo by JP Masclet

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBN 978-1-9821-7973-1

ISBN 978-1-9821-7975-5 (ebook)

To Clemmie, Nathaniel, and Angelica

N OTES ON THE T EXT

D ATES

In the middle of Elizabeths storyon September 2, 1752the calendar changed from the Old Style (Julian) to the New Style (Gregorian), an act introduced by the 4th Earl of Chesterfield to bring Britain into line with most of Western Europe. The act dictated that the new year began on January 1 rather than on March 25 (Lady Day), and meant that eleven days were lost.

Dates before September 2, 1752, are given in the Old Style (not adjusted for the eleven days), but for simplicitys sake I have adapted them to the years that we recognize, that is, JanuaryMarch is made part of the subsequent, rather than the original, year. Dates in Russiathe only country that adhered to the Julian Calendar (until 1918)are sometimes given in both.

In the process of the calendar shift, some people stuck to their old-style birthdays, and others added eleven days. Elizabeth minimized the problem of an altered birthdate by subtracting five years from her age, rather than quibbling over a few days.

M ONEY

If we take an easy-to-multiply figure for the conversion of 1 in 1744 to todays value, There was minimal inflation for most of the century, so as an approximate measurement this works for the whole of Elizabeths lifespan. There were 12 pence in a shilling, 20 shillings in a pound, and 21 shillings in a guinea. A crown was five shillings.

Britain was more financially divided than it is now. Only 3 percent of families had an annual income of 300 or more in the mid-century; the average income in 175960 has been assessed as around 45 a year. Housing and servant labor came cheap; consumables, including food, were high-cost. London, as ever, was more expensive than the rest of the country.

It has been estimated that to live like a gentleman in 1734to be able to afford theater tickets, books, a carriagewould require 500 a year. Elizabeths salary of 200, therefore, was an enormous amount compared to the average wage, but restrictive for someone of no independent means trying to live an upper-class life.

C ONTEMPORARY Q UOTES

I have generally modernized old spelling, capitalization, and punctuation for ease of reading.

. I have chosen the year Elizabeth first drew a salary as maid of honour as the year of comparison.

I NTRODUCTION

In April 1776, the world held its breath.

The determination of George Washingtons band of American revolutionaries was being tested as they prepared for battle to defend New York: would they cede to the British yoke or strike out for independence and unleash the dominance, for the coming centuries, of what was to become the United States of America?

These decisive days were the last time that George III, the Hanoverian British king, could have conceivably held on to his American empire. The British peace commissioner, Admiral Howe, still hoped words rather than bullets might solve the crisis when he arrived on Long Island.

Yet in London, the drama wasincrediblyelsewhere. Among the House of Lords, the judiciary, the press, and the literati, all eyes were on a woman in black, charged with bigamy.

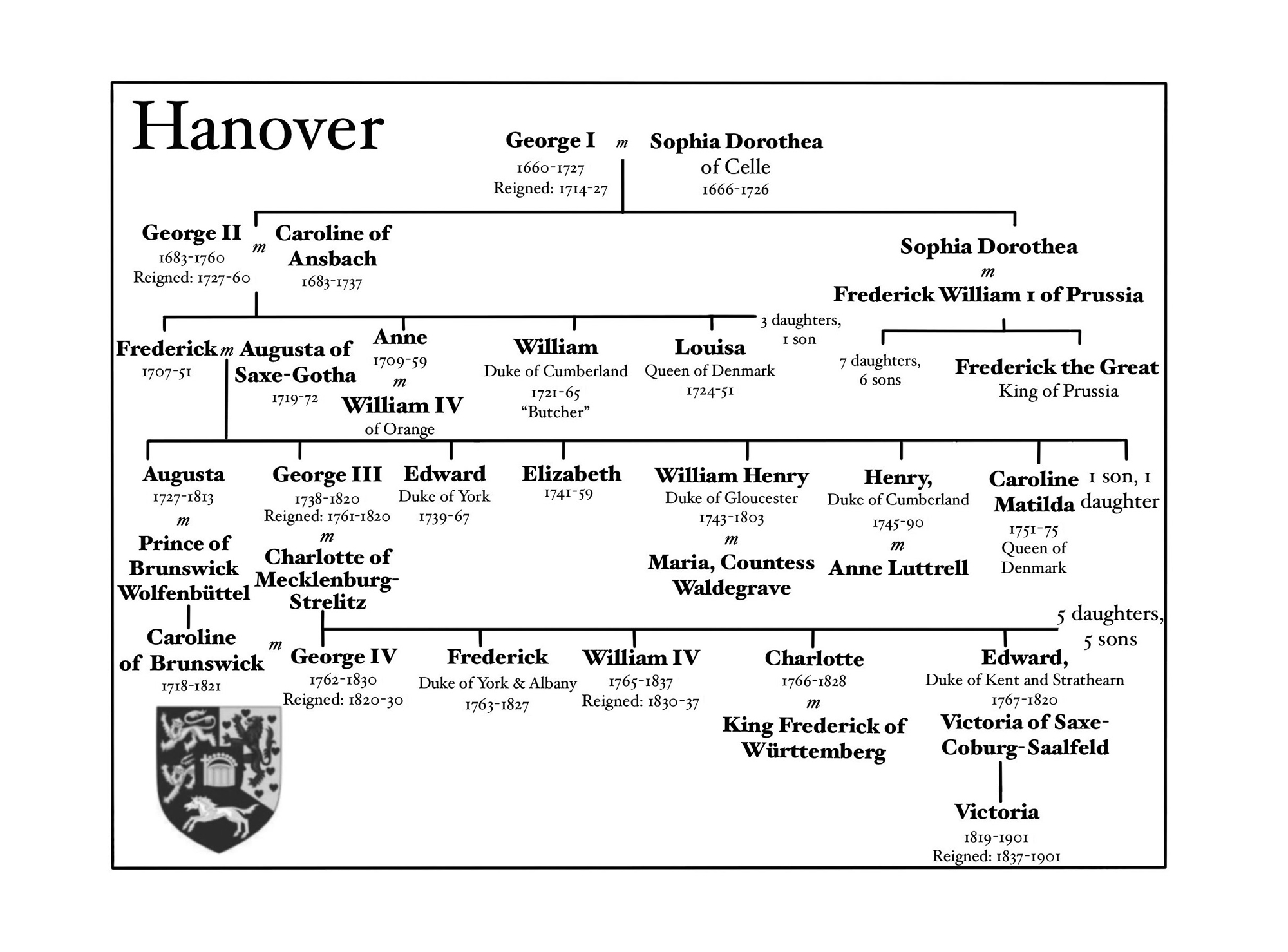

The trial saw the queen, two future kings, Queen Victorias father, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, James Boswell, Horace Walpole, and most of the bishops, peers, and peeresses in the land in Westminster Hall, either as jury or spectator. Half of the Cabinet was there, the secretary of war a witness.

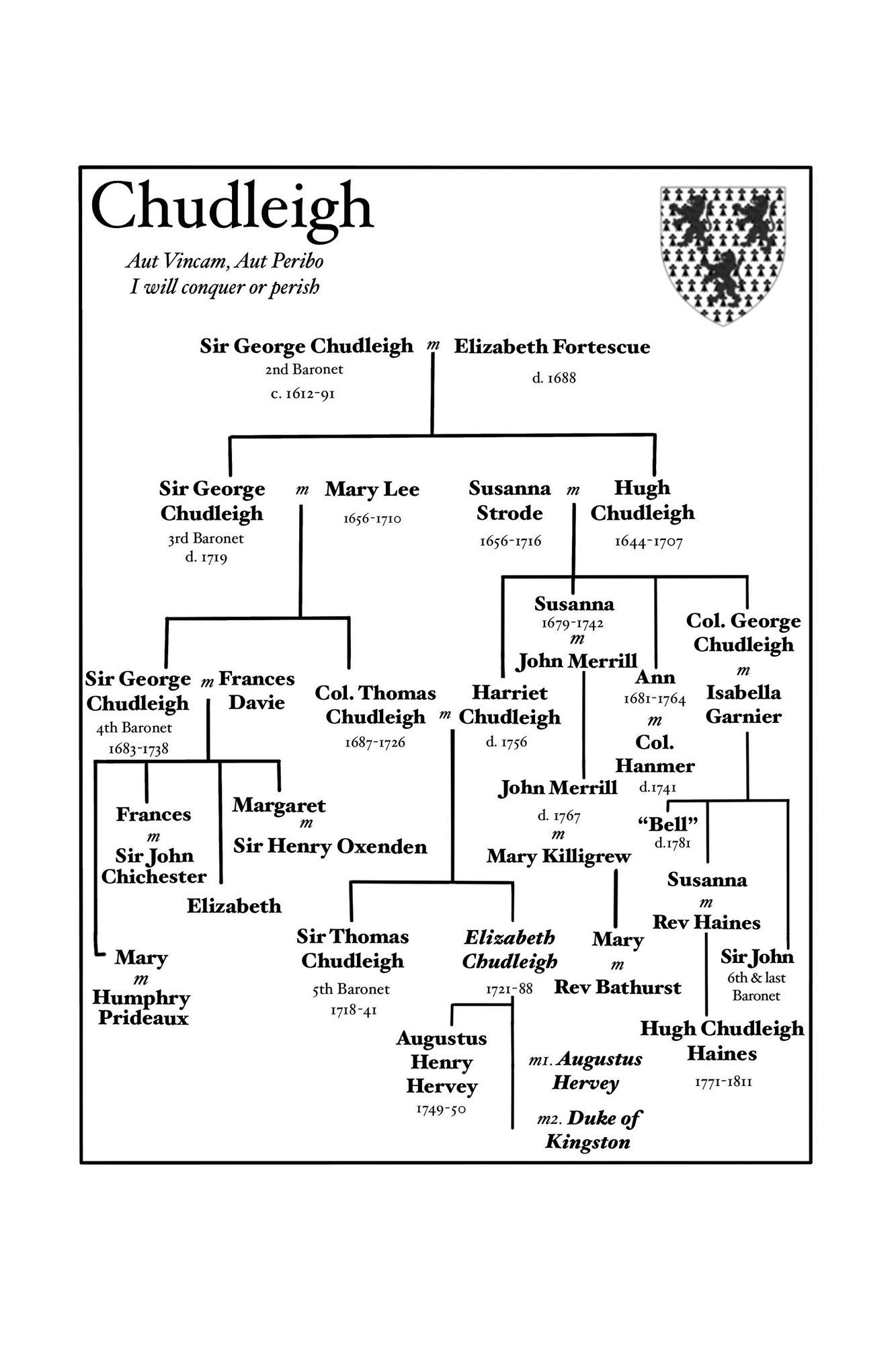

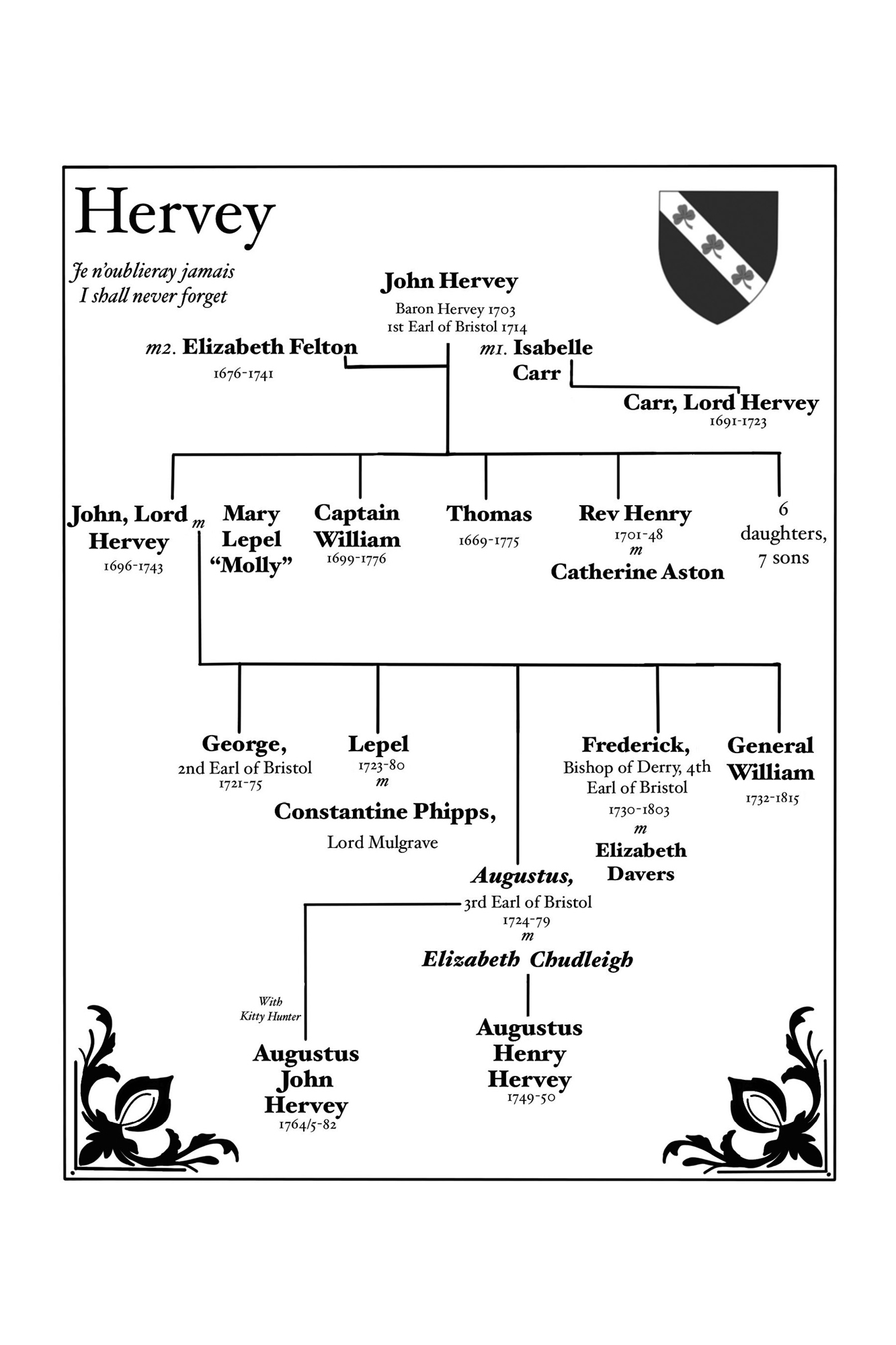

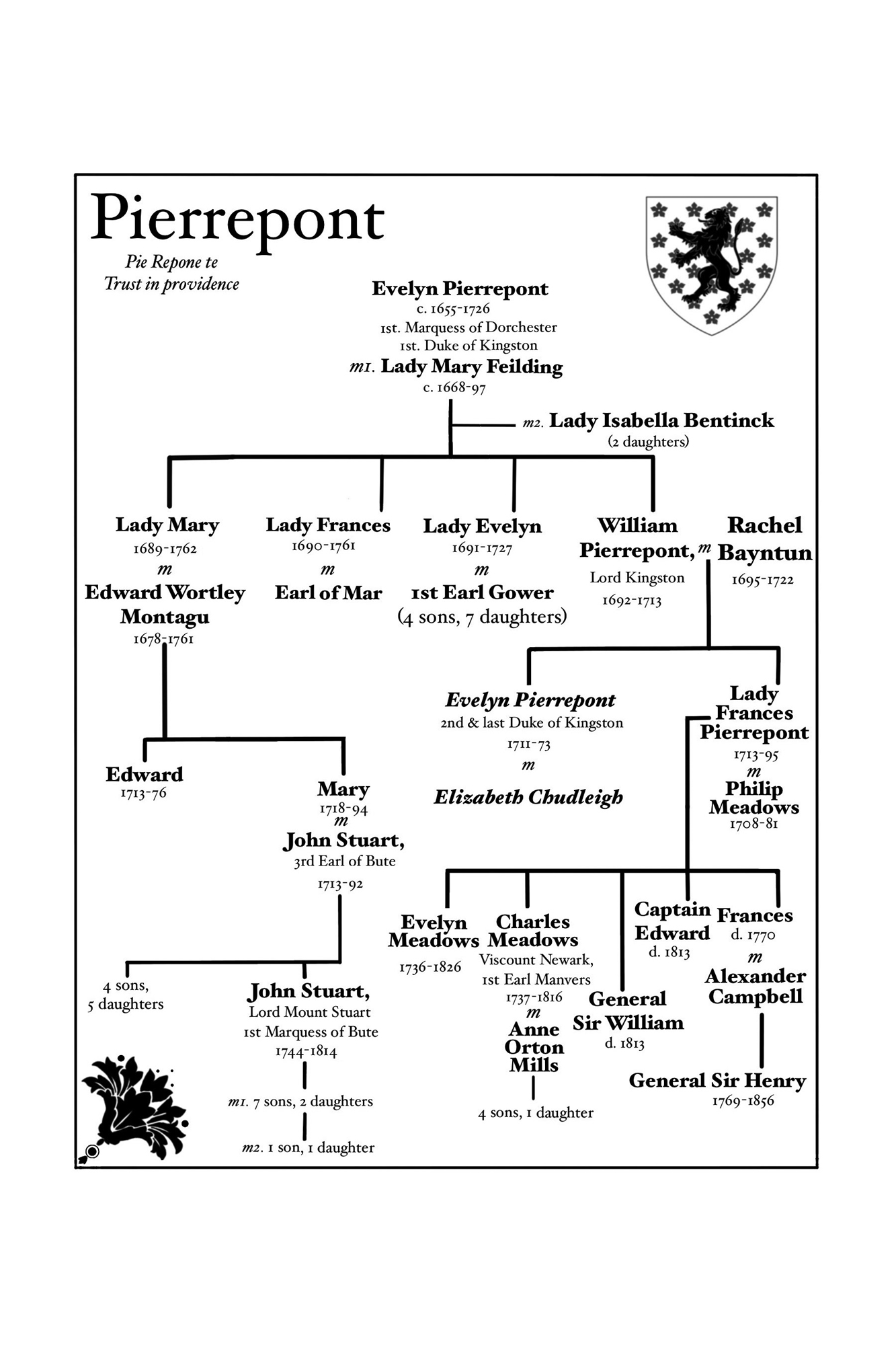

The woman accused was christened Elizabeth Chudleigh, but when she was talked about in the coffeehouses, written about in the penny papers, gossiped about by diarists, and sketched by cartoonists, they more often nicknamed her the Duchess-Countess.

Now we see it more clearly: the distracted incompetence of a tired colonial power engaged in the displacement activity of persecuting an errant, aristocratic woman. But the story of the Duchess-Countess casts other, more human, shafts of light onto this period of history, in which the seeds of so much of our culture were sown: the struggle of a forward-thinking woman in a society undergoing the birth pangs of modernity; the rise of journalism, an incipient always-on form of social media, and its occasionally willing collaborator, the celebrity; the way in which Elizabeth used soft power and the art of public relations, before either had those names.

The Georgian patriarchy had law, land, money, and church on their side: alternative forms of influence had to be found for a woman who wanted to travel, build, and mix as if she were man or monarch.

Duchess, countess, courtier, socialite, hostess, mariner, property developer, celebrity, vodka distiller, press manipulator, arts patron, bigamist: Elizabeth Chudleigh was the great antiheroine of the Georgian era. Her story reads like a dark fairy tale, Cinderella gone hideously, publicly wrong with all the force of a Hogarthian twist, with too many princes and glass slippers left smashed in her wake.

The Hon. Elizabeth Chudleigh, Elizabeth Hervey, Duchess of Kingston, Countess of Bristolby the time she went on trial, no one knew what to call herstarted her life in the public sphere as a maid of honour to the Princess of Wales at the Georgian court, married one man in secret and denied it, only to wed another. She was convicted of bigamy and then pursued across the world by her second husbands relations, the newspapers, and the ill-wishes of her enemies. After her court humiliation, rather than choosing to live out the rest of her days in hermetic retirement or atonement, she went on a floating odyssey from Rome to St. Petersburg, befriending popes, princes, and tsarinas. She became one of the three most talked-about women in Europe, alongside Marie Antoinette and Catherine the Great. The Hermitage in St. Petersburg still possesses the paintings and the giant but delicate musical chandelier she took there to persuade the court to embrace her, taking advantage of the vibrant Anglomania that gripped Imperial Russia at the time.

![Susan Holloway Scott - [Fiction] Duchess: A Novel of Sarah Churchill](/uploads/posts/book/51001/thumbs/susan-holloway-scott-fiction-duchess-a-novel.jpg)

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.