A POST HILL PRESS BOOK

Hello Darkness:

My doctor said, Son, you will be blind tomorrow.

2022 by Sanford D. Greenberg

All Rights Reserved

ISBN: 978-1-63758-274-9

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-63758-275-6

Cover design by Jason Heuer

Interior design and composition by Greg Johnson, Textbook Perfect

This is a work of nonfiction. All people, locations, events, and situations are portrayed to the best of the authors memory.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the written permission of the author and publisher.

Post Hill Press

New York Nashville

posthillpress.com

Published in the United States of America

Distributed by Simon and Schuster

Contents

From the first page to the last, I was captivated by Sandys bright mind, ready wit, and indomitable spirit.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, 19932020

Sandy is my gold standard of decency. I try to be his cantor, the tallis that embraces him.

Art Garfunkel

recording artist, winner of eight Grammy awards, inductee of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

How devastating it would have been to be told at such a young age that you would never see again. What willpower it would have taken to paddle upstream against such a strong current. And how encouraging it is to know it can be done, because Sanford Greenberg did itwith a little help from his friends, but we all need that.

Margaret Atwood

author of The Handmaids Tale and other novels, two-time winner of the Booker Prize

For Sue, the one who has always been there

the dark beyond dark

the door to all beginnings

Lao-Tzu , Tao Te Ching

Y ou would think that a book about a young man going blind would be very sad. I went blind at age nineteen, and, yes, there were some awfully hard times. But my story is more than a tragedy. In fact, its not really a tragedy at all.

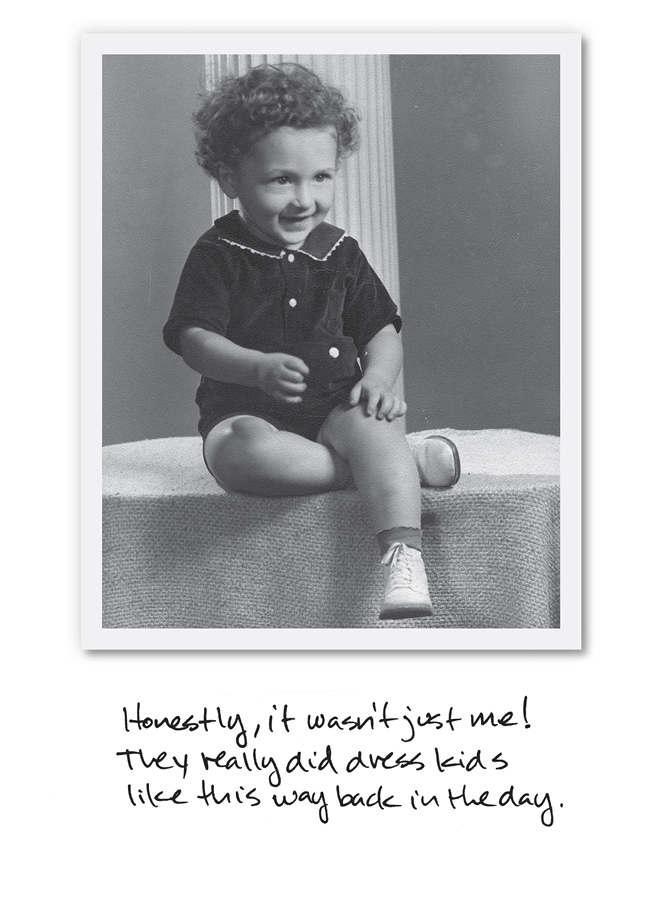

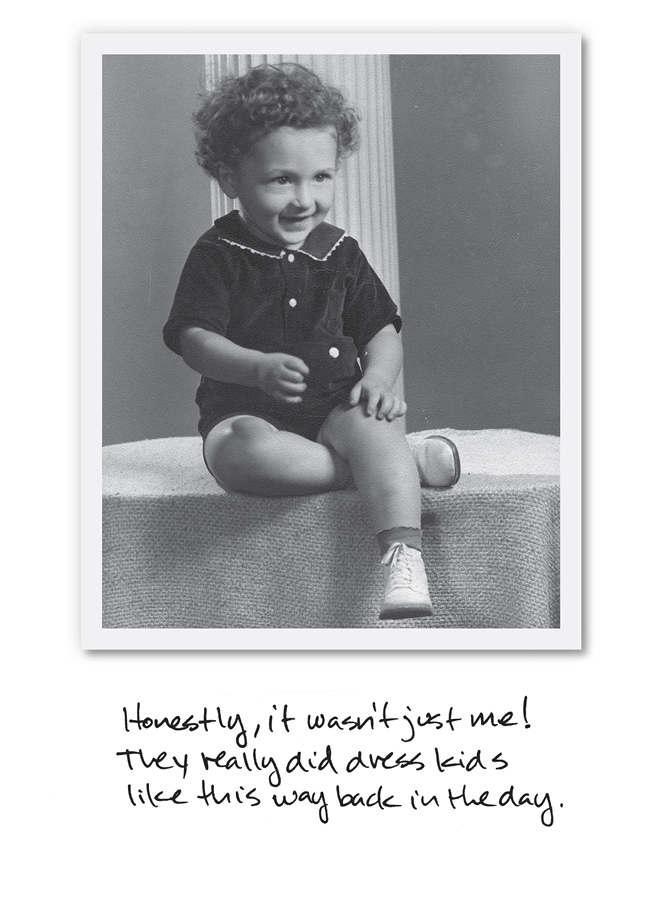

I think of my life in three acts, like a play. In Act One, I was a young boy, raised by poor but loving parents just after World War II.

In Act Two, I went to a great college and had a promising future ahead of me. Then wham! I got a disease that left me blind.

In Act Threewell, youll just have to read this book to find out what happened. Along the way there are tears and laughter, painful moments and wonderful times.

When you go blind after nineteen years, you remember a lot of what the world looked like. You remember all kinds of things. After I went blind, my memory became like muscle that grew stronger every day. I remember so much that I just had to write it down. What follows are some of the low and high points of my life.

H ave you ever had a dream that you dreamed many times? Not every night, but maybe a few times a year? This happened to me a long time ago when I was a boy. The dream was not a happy one, but its important to my story, so Ill tell it to you.

In the dream it is a sunny late-summer day at Crystal Beach in Canada, just west of Buffalo, New York. A tall, handsome father in a bathing suit is carrying his five-year-old son on his back about twenty yards from shore out into Lake Erie. Both are laughing as the father runs through the waves. The father playfully lowers himself and his son into the lake, and as the water slaps at the childs bathing suit, the boy begins to tremble and laugh. Danger excites him; he has never been out in the water before. But in his fathers arms he is safe.

Suddenly, the father, still holding the boy, turns and pushes through the water toward the shore. The boy is surprised and at first amused. At the shoreline, the father hesitates for an instant. Then he slams facedown on the hard, wet sand, forcing the boys face into it. The boy rolls his father over and sees his glazed and vacant eyes. The father is dead. The boy sits and stares blankly.

The reason for this dream is clear. In 1946, I went on my first trip to the beach. Later that same year, my father died. The beach trip was an important early memory, but soon after, a bigger event happenedthe death of my fatherand my dream mixed the two together.

My father, Albert Greenberg, was a tailor who had to work long, hard hours to provide for his family. He had very little time left over to spend with his children. I admired him, but since he died when I was five years old, I dont have many memories of him.

I remember his last morning. My little brother, Joel, and I walked him to the streetcar stop and waved goodbye as he left for work. We found out later that at lunchtime he walked to the corner pharmacy, where he collapsed and died. I never knew exactly what he died of. Probably a heart attack from years of stress. Albert grew up in a small village in Poland, in Eastern Europe. He was Jewish, and this was a very bad time to be Jewish in Eastern Europe. Because times were hard, people often took their frustrations out on Jewish people, smashing up their shops and homes and making life miserable for them.

In 1934, Albert, as a young man, moved with his family to Cologne, Germany. Cologne was a city of culture and refinement, so they thought it would be a better place for a Jewish family. Boy were they wrong!

The Nazis had just come to power in Germany. They began rounding up Jewish people and sending them to concentration camps, where they were forced to work as slaves. Many died or were killed. Albert and a group of his family and friends made it out of Germany just in time. They spent many months wandering about Europe, walking from place to place, knocking on doors, looking for shelter. They were lucky to find people kind and brave enough to help them. Finally, in 1939, almost two years before I was born, they made it to Paris, France. But the Nazis were not far behind. My father and the others migrated to the United States just before the Nazis invaded France.

He settled in Buffalo, New York, where he was free to earn a living without being persecuted for being Jewish. But he never lost the habit of looking over his shoulder for danger. The stress finally caught up to him that day inside the pharmacy in Buffalo.

That evening, his coffin lay in the center of our living room in Buffalo, draped with a black velvet cloth embroidered with a Star of David. I thought the cloth was keeping him warm. Remember, I was five years old. I knew he was dead, but I didnt really know what that meant. Candles representing the divine spark in the human body burned in red glass containers. I touched the coffin with my fingers, playing on it as if it were a piano. I sat under it like a good boy. I fiddled with the loose stitching of the cloth that hung below the bottom of the casket. I knew it was a terrible occasion, though I did not know precisely why. I was frightened and confused.

Then came the burial. It was a bleak, gray day. Wind swept across the cemetery. We huddled together like peasants. I stood among the adults at the burial site, unable to make sense of the silent sceneas perhaps no five-year-old could. The mounds of dirt surrounded a large rectangular hole in the earth. The coffin rested to one side. Amid the sobs of those gathered around me, the rabbi began chanting a prayer. We put my father in the ground. The coffin was lowered on worn leather straps until it was nearly at the bottom. There were only a few inches between him and the cold ground, but in my mind he wasnt quite buried yet. And so that meant maybe he wasnt really dead. We could open the coffin. He could come out. Climb out of the hole, come home, and shower. Have lunch, live a good, long life.

Next page