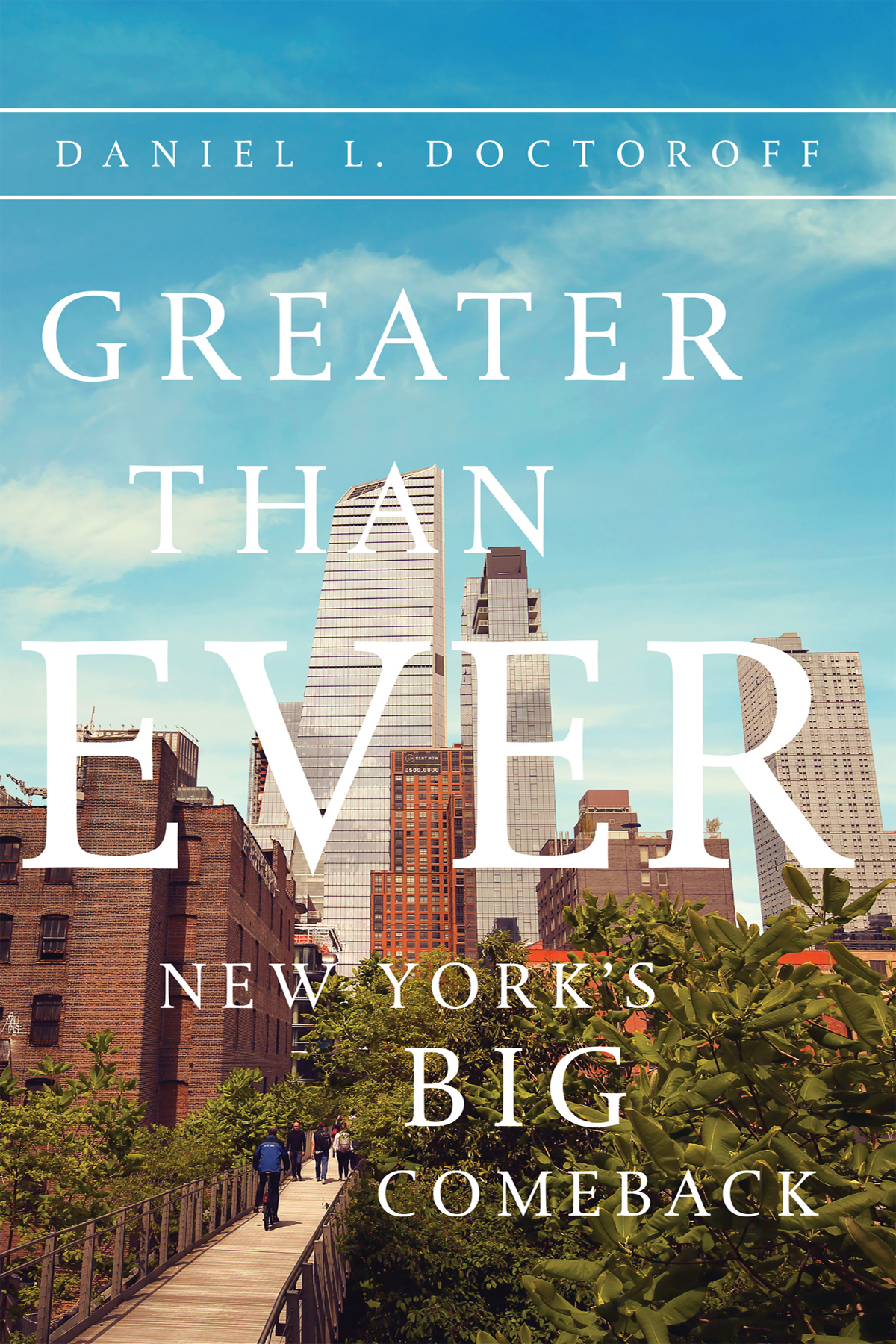

Copyright 2017 by Daniel L. Doctoroff.

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call 866-376-6591.

Names: Doctoroff, Daniel L., author.

Title: Greater than ever : New Yorks big comeback / Daniel L. Doctoroff.

Description: First edition. | New York : PublicAffairs, [2017] | Includes index.

Subjects: LCSH: Doctoroff, Daniel L. | New York (N.Y.). Office of the Mayor--Officials and employees--Biography. | City managers--New York (State)--New York. | Olympic host city selection--2012. | Economic development--New York (State)--New York. | Urban renewal--New York (State)--New York. | City planning--New York (State)--New York. | New York (N.Y.)--Politics and government1951

I VIVIDLY REMEMBER my first visit to New York City; it was hate at first sight.

It was the summer of 1968, and I had just turned ten. A typical summer vacation for our family was a long car trip from our home in suburban Detroit to the East Coast. My parents packed my three younger brothers and me into our 1965 dark-blue Impala station wagon, and we headed first to Montreal to see Expo 1967, one year late, then down through Vermont and on to the obligatory stop in Boston, where our grandparents lived. Before heading home, Mom and Dad decided to visit my Dads brother, Mike, and his family, who had just moved to Brookfield, Connecticut, about seventy miles from New York City.

On the spur of the moment, the adults decided it would be fun to go see the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus at the then-new Madison Square Garden. Back into the station wagon we piled, and we headed for New York City for a day trip.

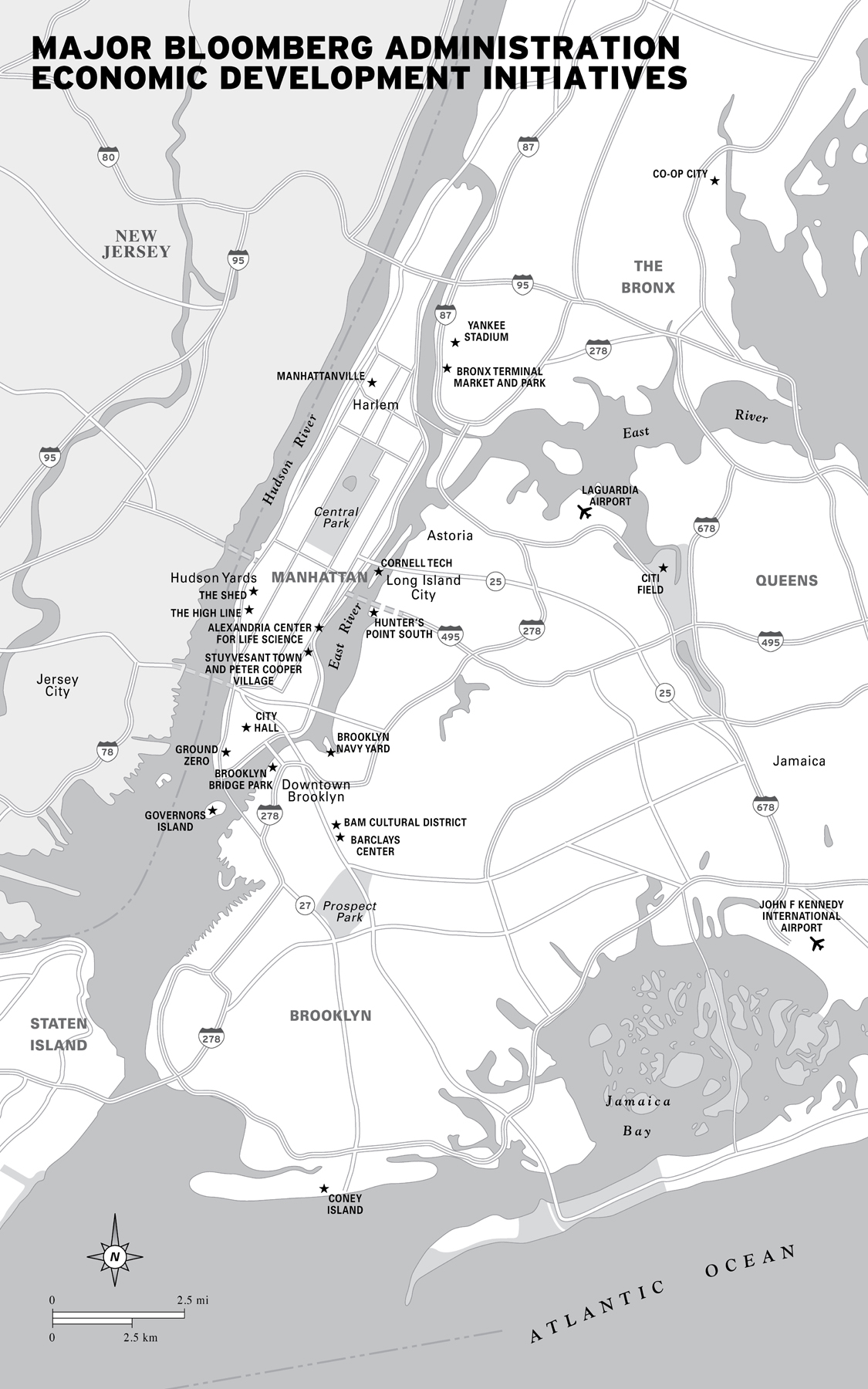

It was the kind of grayish, sweltering, August day that made the air above the road shimmer in waves. As we drove south on the highway, just past the sign that said Entering New York City, I was in the backseat on the left side staring out the window when I suddenly saw in the distance what looked like an alien city. As we drove closer, the outlines of dozens of seemingly identical brown buildings piercing the sky grew clearer. They seemed to be replicating, with more anonymous clones under constructiona vast, bleak, spreading mass. In the foreground was a dump. My dad announced that this was Co-op City.

Co-op City was built in the 1960s and early 1970s as a new type of development for middle-income New Yorkers. An unprecedented endeavor, it is still the largest single residential development in the United Statesthirty-seven towers plus garages, schools, and its own postal code.

I knew none of that as we drove by, but just that the uniform towers, alone in the distance, looked monstrous. They were the first image I had of New York. I am never going to live in this city, I shouted out from the backseat.

Despite my resolution, on January 1, 2002, I stood on a ledge of a damaged skyscraper looking down on Ground Zero and realized that my fate was intertwined with the future of New York. At that moment, as I contemplated the twisted wreckage, I was overcome by my responsibility as the new Deputy Mayor for Economic Development and Rebuilding for the Michael Bloomberg Administration, not only to oversee the rebuilding of the World Trade Center site but also to consider New York Citys place in the world.

In the wake of September 11, 2001, fundamental questions about the practicality of cities across the countryand indeed the entire free worldwere raised. Were great cities still possible? Could millions of people live together safely and even thrive in a world that faced unprecedented economic, security, and even existential threats? New York had always stood alone among cities for its openness and ambition. Now people were questioning whether the very things that made the city so unique could continue.

Less than two months earlier, on November 11, 2001, the New York Times had run a front-page story outlining a bleak possible future: The slowing economy, the collapse of the dot-com bubble and the impact of September 11 have raised the specter of the citys enduring another period of austerity, a return to the days of dirtier streets, legions of the homeless, an increase in the welfare population, a rise in crime, a plummet in the quality of life so sharp that people fled town.

The writers were right to be worried. On January 1, 2002, it was fair to question the very premise of New York. In the three months after the attack that spanned roughly seventeen minutes, New York City lost approximately 430,000 jobs and $2.8 billion in wages. Gross domestic product (GDP) for the city declined by an estimated $11.5 billion by the end of 2001, resulting in more than $2 billion in lost tax revenues. Approximately 18,000 small businesses were destroyed or displaced after the attacks. In some neighborhoods around Ground Zero, vacancy rates shot to over 40 percent.

Cornerstone businesses such as American Express and Lehman Brothers had to abandon their smoldering headquarters. In fact, New York City lost 25,000 of its 208,000 security-industry jobs in the month after the attacks.

For a city highly dependent on its financial services sector, this could have been a crippling blow by itself. It was made worse by the shattering of the citys second most important industrytourism, which employed 263,000 people and generated $25 billion per year. The number of tourists plummeted by almost 50 percent, dropping hotel occupancy below 40 percent; 3,000 employees in the travel and tourism industry were laid off in a single week after the attack.

September 11 could have broken the citys back, forever associating New York with its most famous disaster. But New Yorkers, aided by people from around the world, took the challenge to heart. This book is the story of some of the people who rose to that challenge in, or in partnership with, the citys mayoral administration. By the time Mike Bloomberg completed his third term at the end of 2013, New York was in remarkable shape.

Although the financial rebound was spectacular, I suspect that when the legacy of this time is judged generations from now, the history books will focus not on the money but on what was built with it. The Bloomberg years changed the physical nature of the city in ways that will undergird prosperity for decades.

Back in 2001, there had been little physical change to the city for nearly a half century. There were many reasons for this, including the fact that New York had been too budget-strapped to invest and that trauma from development catastrophes in the 1960s, such as tearing down the original, extraordinary Pennsylvania Station, had left the city paralyzed.