1.

An Android at the Opera

1.1

Deep inside your ear, between the outer parts you can see and the inner parts that you cant, there is a thin cone of flesh called the tympanumor ear drum. Its job is to convert the vibrations of sound waves passing through the air into mechanical vibrations that your brain can understand.

For over a hundred years, whenever people built machines to listen for uslike telephones, walkie talkies, or hi-fi equipment they based the working of those machines on the tympanum. Today, still, all technologies for capturing and reproducing sound are based upon the working of the ear.

Three hundred years ago, when no-one was very much interested in the ear and even ear doctors were dismissed by their colleagues as mere aurists, the model for sound technologies was not the ear, but the mouth.

To reproduce the workings of the human mouth was thought by some to be just a few steps from reproducing the soul.

The people whose job it was to undertake such a task were not scientist-entrepreneurs like Thomas Edison or Alexander Graham Bell, but clockmakers.

The greatest of these mechanical geniuses was a Frenchman named Jacques de Vaucanson.

1.2

When Jacques de Vaucanson was a child, growing up in the town of Grenoble in the east of France, his mother would take him to church with her every week.

While she was in with the priest, the young Jacques would stare up at the clock in the church tower. As his mother whispered her confession, the clock ticked on resolutely and Jacques gazed rapt at its perfect, regular movements.

Day after day he stared at that clock. So long and so intently did he gaze at its hypnotic motions that finally he was able to go home and build one himself, just the same, from scratch.

1.3

Throughout his childhood, Vaucanson loved fixing and building things: clocks and pocket watches, wind-up toys and cigar boxes. Whenever anyone had something that needed mending, it was to Jacques Vaucanson that they took it.

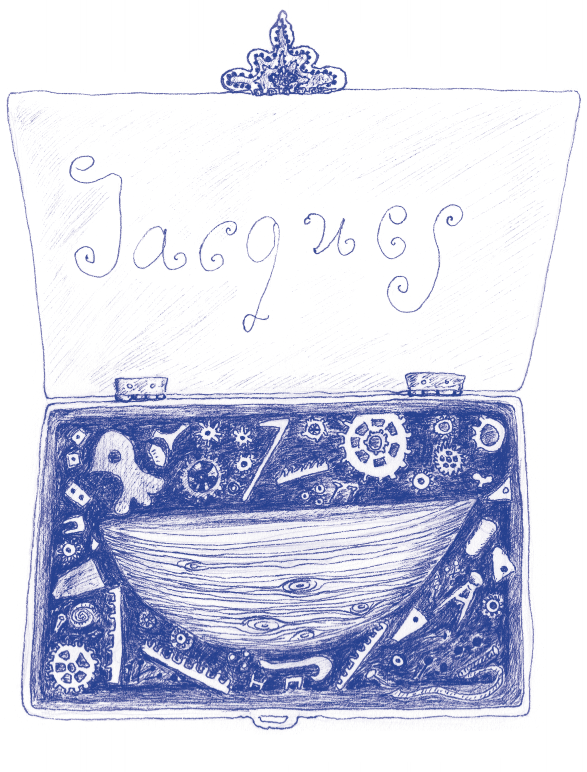

On his first day at school, he arrived clutching a little metal box. An unsociable child, he seemed distracted during his lessons, intent on guarding the contents of his mysterious box.

Finally, the Father Superior forced young Jacques to open up and reveal the contents of his box. Inside, he found a myriad of little cogs and wheels, nestled amongst fragments of the hull of a small model boat.

I cannot study, Vaucanson swore, until I have constructed a boat that will cross, by its own power, the great school pond.

The Father Superior chastised the eager boy and sent him to his room. But two days later, Vaucanson emerged with his boat intact. He wound it up and set it to water and the little boat crossed the pond with ease.

1.4

Vaucansons ambition would not rest with clocks and boats. He dreamt of building a man.

His first efforts, however, did not meet with acclaim.

At 18, he joined a monastery in Lyon as a novice. Fond of the boy and keen to nurture his talents, the monks gave Jacques his own workshop.

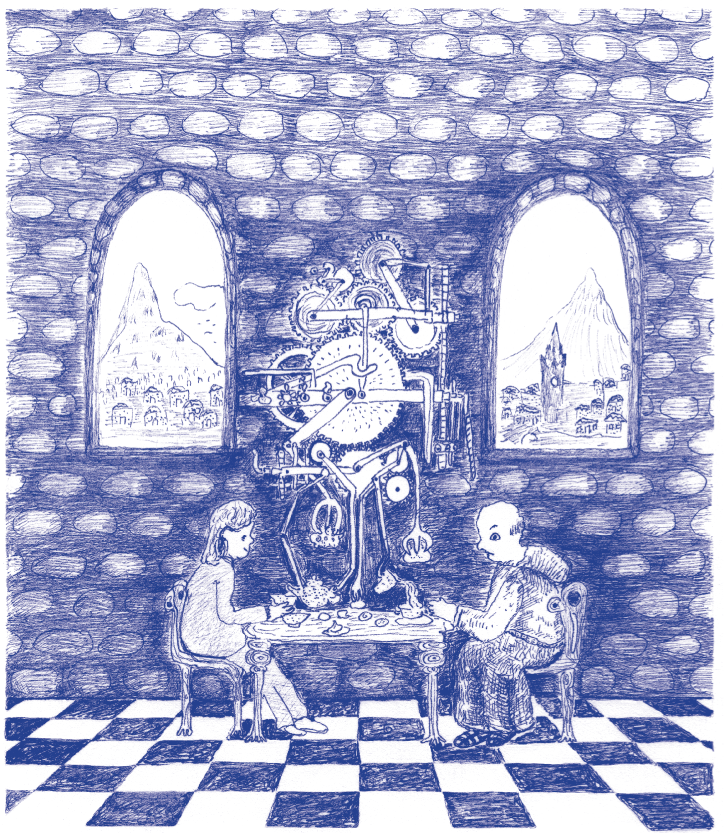

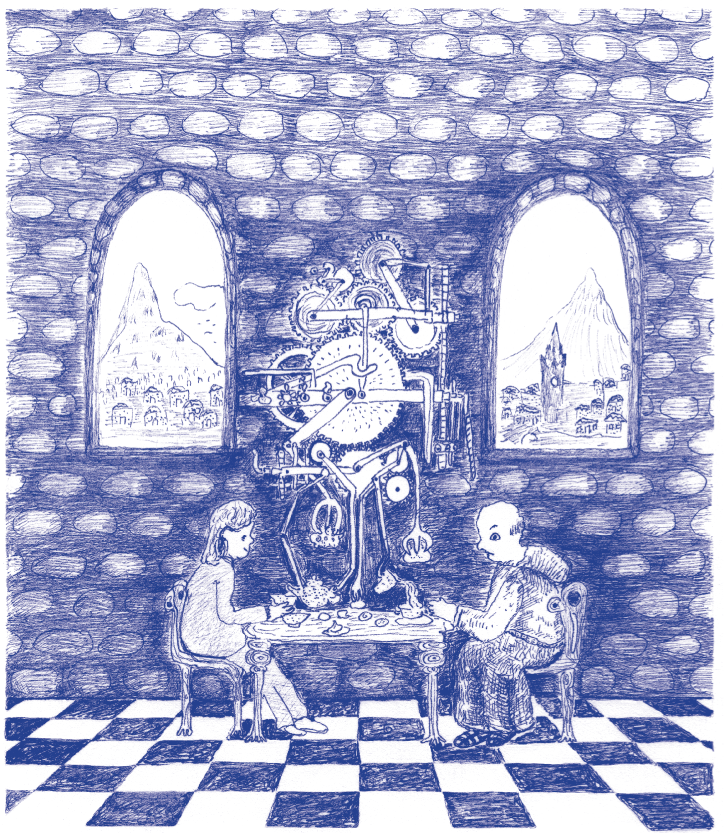

One day, seeking to impress his superior, Vaucanson invited the abbot to his workshop for tea. When the monk was greeted, not by servants, but mechanical automatons, there to serve his cake and wipe his plate, he screamed blasphemy and promptly evicted the young novice from his workshop.

It was then, cast out into the world to seek his fortune alone, that Jacques de Vaucanson set to work on his most prized invention of all.

1.5

By the time he came to present it before the public in 1738, Vaucansons mechanical flute player was by far the most complicated machine he had ever attempted. At four and a half foot tall, it was almost life-size, modelled on a famous statue in the Tuileries Garden of a faun sat on a rock, playing a tune.

But Vaucansons flautist could really playand it could play any flute you put in its hands. It blew through the mouthpiece (thanks to a pair of bellows for lungs) and fingered the holes (with soft leather pads to add delicacy to its hard wooden fingers) just like a real flute player.

Though its workings were like a grandfather clock, with its wheels and pulleys and weights, no-one had ever seen anything quite like Vaucansons flute player before. The philosophers of his day called it an androidean automaton in the figure of a human, which performs functions outwardly similar to those of a man. One writer, a doctor notorious for his outspoken materialist views, said publicly that if now Vaucanson could only make a machine that talked he would be tantamount to a god.

1.6

Vaucanson never succeeded in making a speaking machine, though he worked on it off and on for the rest of his long life. Not content with a machine that merely breathed and piped upon its rock, he dreamed of building a man with blood in its veins and a song in its heart. He never succeeded.

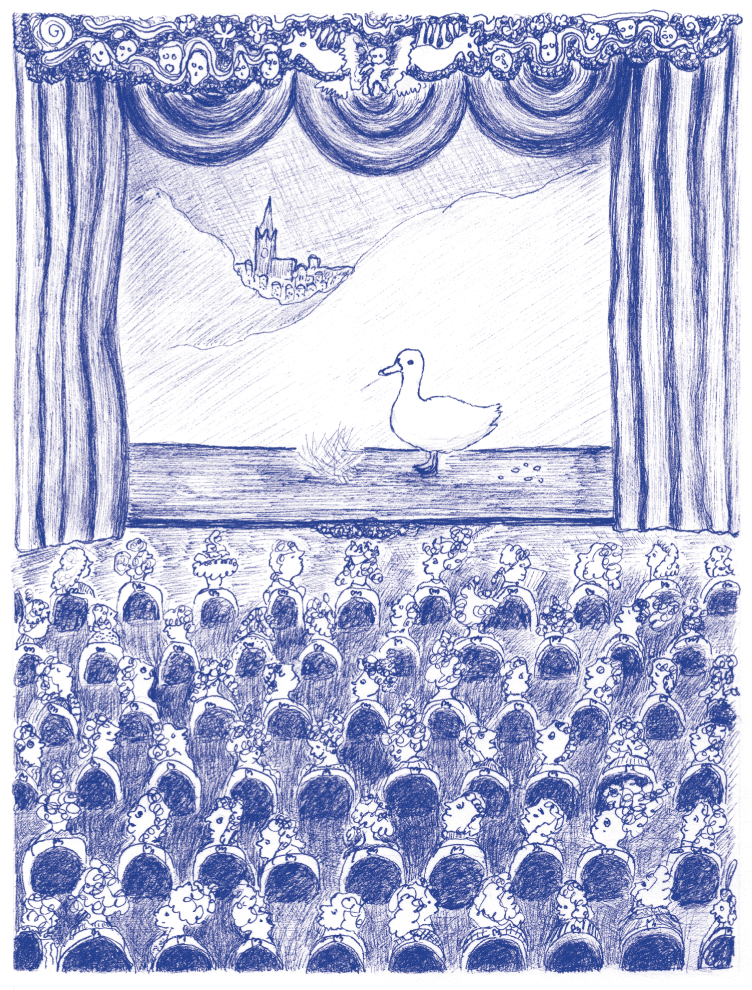

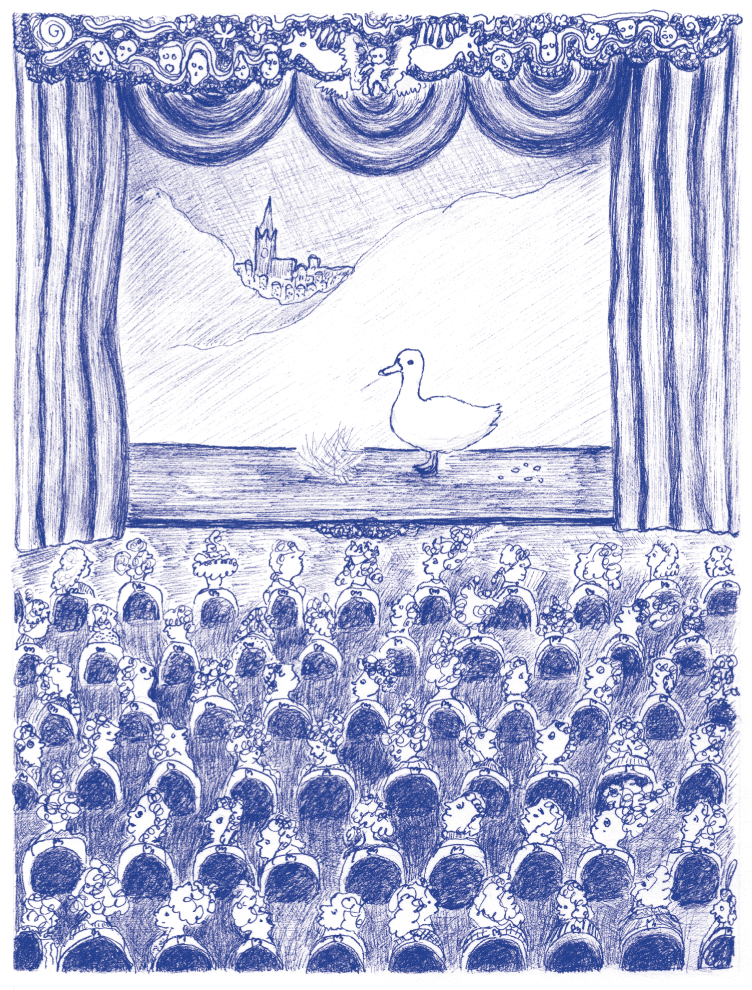

His flute player took him from the town fair to the salon parties of high society, to the academy of science and even to the court of the King himself. Finally, in 1742, Vaucansons flautist and other machines were put on the stage of His Majestys Opera House on the Haymarket in London. Upon boards trod by the great virtuosos of the day stood Vaucansons flute-player, trilling on its pipe.

But the star of the opera house show, the mechanical marvel that became the toast of London town, was finally not the flautist, but another invention of Vaucansons: a golden duck that could eat corn, chew his supper and then discharge it as the inventor himself put it, at the other end. Once wound up and left to its own devices, Vaucansons golden bird would even go quack, just like a real duck.

2.

The Chord of Power

2.1

John Keely had a secret.

In 1872, he announced his discovery of a new form of energy. He called it the force and claimed it could power a train from West Philadelphia to New York without fuel, without smoke, and without noise.

He said it could suspend gravity itself, that it could power a spaceship to the stars.

It possessed, he swore, an elastic energy of 10,000 pounds to the square inch.

It harnessed, he claimed, the ether itselfthe very space between atoms, the medium through which light moves.

Keely was far from alone amongst men of the late nineteenth century in his promise of limitless energy for free.

Next page