First published by Pitch Publishing, 2016

Pitch Publishing

A2 Yeoman Gate

Yeoman Way

Durrington

BN13 3QZ

www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

Spencer Vignes, 2016

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher.

A CIP catalogue record is available for this book from the British Library

Print ISBN 978-1-78531-160-4

eBook ISBN: 978-1-78531-241-0

--

Ebook Conversion by www.eBookPartnership.com

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book would never have been written had it not been for two people.

First, Dick Jenkins (christened Daniel Cecil Richmond Roose Jenkins, but known to most simply as Dick). It was in 2000 that I received a phone call telling me that Leigh Rooses nephew was still alive and living in Shrewsbury. Dick was 96 years old at the time with a hazy short-term memory. Fortunately, his long-term memory was razor sharp. He told me stories aplenty about Leigh and the Roose family which I taped on a Dictaphone while downing multiple glasses of sherry (I dont even drink sherry, but it seemed like the polite thing to do). Listening back to our conversations, I confess I was guilty of questioning some of the finer points because it had all happened so long ago. The mind can play tricks on a 31-year-old, which I was in 2000, let alone a stalwart of 96. And yet my subsequent research elsewhere substantiated everything that Dick had said. Meeting him kick-started the process which transformed Leighs story from what would have been a newspaper or magazine article into a book.

The second person has no known name, and heres why. During the First World War various soldiers were assigned the task of keeping their respective battalion diaries up to date. Some chose to write only a sentence or two each day, if that. Others however took to the task with gusto logging as much information as they could location, orders from on high, details of enemy action, casualties, amusing incidents, commendations for bravery, the lot. Whoever was in charge of the regimental diary for the 9th Royal Fusiliers between late August and October of 1916 belonged firmly in the latter category. His identity went unrecorded, but hes the reason I was able to piece together Leighs time with the battalion in France and the circumstances surrounding his last known sighting. Chapter One and Chapter Nine of this book are as much the unknown soldiers work as mine.

For providing information and support I would also like to thank Hazel Bailey at Stoke City, Sue Beaumont at Huddersfield Town, David Barber, Dominic Cakebread, Neil Coyte, Allison Dowzell and Arwyn Williams at Wales Screen, Helen Fisher of the Cadbury Research Library at the University of Birmingham, Peter Francis at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, Ian Garland, Reg Gibbs, Ceidiog Hughes, David Jenkins, Geraint Jenkins, Nick Jenkins, Gil Jones, Rob Mason at Sunderland Football Club, Pam and Ken Linge at The Thiepval Project, Ken Montgomery at YMCA England, Brian Payne, Sue Payne, Olwen Roose Jones, Gordon Lock, Ian Salmon, Ceri Stennett, Neville Southall, Arthur Tapp, Derek Tapp, Gaynor Tinsdale, Vanessa Toulmin, Alex Vignes, Sally Vignes, Paul Wharton and everyone at the Everton Football Club Heritage Society, Aberystwyth Library, Arsenal Football Club, Aston Villa Football Club, the British Film Institute, Cardiff Central Library, the Imperial War Museum (London), Kings College Hospital (London), Manchester Central Library, the National Screen & Sound Archive of Wales (Aberystwyth), the Public Record Office (Kew), Stoke Library, Sunderland City Library and Wrexham Library.

A big tip of the hat to Pitch Publishing in particular Paul Camillin, Jane Camillin, Graham Hales and Dean Rockett for being so easy to work with and helping to bring Leigh back into the public domain after so many years in the wilderness.

Authors couldnt exist without the love, support and understanding of those closest to home, so last but certainly not least thank you to my partner Jane and children Rhiannon and Luca for living under Leighs long shadow for all these years.

For Rhiannon, and

in memory of all the

missing from World

War One

Before you go to war, say a prayer.

Before going to sea, say two prayers.

Before marrying, say three prayers.

Before deciding to become a goalkeeper, say four prayers.

Leigh Roose

Introduction

D EAR reader, you and I should really have become acquainted back in 2007. That was when this book was originally due to see the light of day. The reason why it didnt is the stuff of every authors nightmares.

Picture this. You have been working on a biography about a trailblazing football player and war hero, a labour of love almost eight years in the making. You finish the final manuscript and hand it over to the publisher. They promise the world in terms of marketing and distribution, say how excited they are to be associated with a book thats poles apart from the carefully choreographed My Story claptrap released in the name of so many cossetted modern day players. Then it all goes quiet. Too quiet. You hope everything is in hand, but deep down theres a nagging sense that all isnt what its supposed to be. The advance you were promised months ago still hasnt materialised. You make phone calls seeking reassurances. Its OK, you are told this is what happens in between the manuscript being delivered and the finished article hitting the shops. The calm before the storm. But dont worry. Everyone here is really, really excited about your book.

And then, the very same week that it is due for release, your worst suspicions are confirmed.....

The publisher has gone into receivership.

To make matters worse, you hear the news second hand. You call the publishers offices but nobody is picking up the phones. You seek answers. You need answers. None are forthcoming. In the meantime your labour of love sinks without a trace. A few review copies make it out of the warehouse onto the desks of journalists who write glowing reviews about a paperback that will never see a bookshop. In some kind of morally questionable deal which you dont fully understand the rights are later assumed by another publisher who, because your book is old news, literally shelves it. At some stage theres a clear-out in the warehouse and all copies are either binned or pulped. You dont know when this occurred. Youre not told anything.

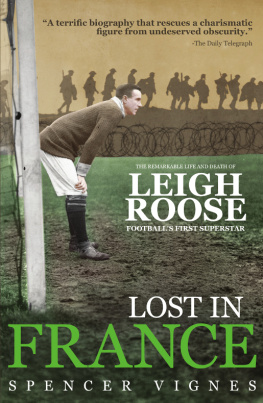

All of this really happened to Lost In France, my labour of love. What does such an experience do to an authors state of mind? You dont want to know.

Its at times like these that a degree of perspective comes in handy. To quote Boris Becker after he famously exited the 1987 Wimbledon Championships at the hands of a journeyman Australian by the name of Peter Doohan, Of course I am disappointed but I didnt lose a war. There is no one dead. It was just a tennis match. How damn true. And, let me tell you, theres nothing like writing a non-fiction book in which the First World War plays a pivotal role to put your so-called troubles well and truly in the shade. Sure, I felt broken, but I also knew once Id managed to re-secure the rights (which took another eight long years) that I would want another crack at