INTRODUCTION

NYC Ghosts & Flowers

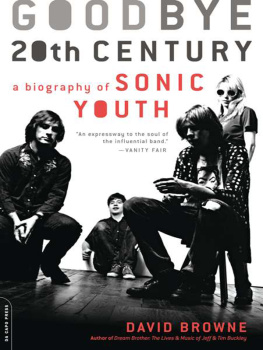

T he first time I met Sonic Youth, they didnt disappoint. Profiling the group for UK heavy rock weekly Kerrang! a broad enough church to encompass avant eggheads like the Youth alongside the rockers and punks and cathedral-burners who typically flood the magazine around the time of their Murray Street album in 2002, I interviewed them en masse backstage at Londons Shepherd Bush Empire, where they were playing that night.

On the walls of the dressing room in this one-time music hall and BBC television studio were old playbills and posters for past events, including one for former Rolling Stones bassist Bill Wymans all-star group The Rhythm Kings. By way of opening gambit, I contrasted the Stones still coining filthy lucre touring songs theyd written as spry young men 40 years before with Sonic Youth, two decades into their own career but eschewing easy nostalgia in favour of new material that was among the best theyd ever recorded. This admittedly soft-ball conversation-starter, I hoped, would prompt the Youth to discuss their longevity and their enduring creative focus.

Jagger, yooooooouuuu suuuuuuuuuuck! yelled Thurston Moore, at the top of his lungs, in adenoidal Yank slur, as the interview swiftly devolved into a five-person symposium on the merits of The Rolling Stones, offering an insight into the personalities of the various members of the Youth.

There was Thurston, arguing that Mick Jagger was a roundly substandard rock lyricist, and that Bill Wyman didnt fit in and should quit the band, attacking his theme with the gusto of a lifelong record nerd. There was Lee Ranaldo, cool and bemused, indulgently informing his band-mate and friend that Wyman had in fact quit the group almost a decade before. There was Kim Gordon, wisely maintaining a mature detachment from the melee, and suggesting that Jaggers lyrics were perhaps undone by his faux-American accent. There was Jim ORourke, sitting cross-legged at Thurstons feet and expounding upon the more obscure corners of Bill Wymans solo catalogue. And there was Steve Shelley, looking up to the sky and softly asking himself, How did we end up talking about Bill Wyman?

Though this hubbub didnt yield much material for my feature, for a young writer meeting his heroes for the first time, it was a pretty heady experience. Buying their Bad Moon Rising album on recommendation of a piece by Keith Cameron in NME tracing the origins of Nirvana, blew this 16-year-old Pearl Jam fans mind, opening up a universe of subterranean, experimental and avant-garde thrills to explore (I know this experience is common for many of my generation). And here they were, behaving exactly like Id always thought they might: irascible, funny and sharp pop-cultural obsessives. It was like meeting the actors from your favourite TV show, and discovering they behaved like their characters off-set.

Im listening to a lot of commune-rock at the moment, announced Thurston, faux-loftily, seeming eerily identical to the Thurston Id come to know from interviews Id pored over, and his narratorial turns in Dave Markeys rockumentary 1991: The Year Punk Broke. Its music made in hippy communes during the Seventies. Free love, free music, free acid. Steve listens to a lot of ska and rock-steady. Lee listens to fuckin Dylan and Springsteen, maaaan. And Jim We knocked on his hotel door the other day, and he came out in a dressing gown, trailed by a cloud of Gauloise cigarette smoke, with this high-pitched whiny noise coming from his room. I asked him what he was doing. He said, Listening to music.

A couple of years later, for Loose Lips Sink Ships, an underground magazine I edit with photographer Steve Gullick, I again interviewed Thurston and Kim, this time on a one-to-one basis, at the 2004 All Tomorrows Parties festival, which they helped curate. In their chalet at Camber Sands Holiday Village, Thurston greeted a seemingly endless stream of visitors, proffering records and fanzines as gifts to the Noise-Rock Monarch. Later, Thurston railed at the Bush administration and the Iraq war, talked about obscure corners of Sonic Youths career, and spoke glowingly of the groups who were playing the festival, artists who had seemingly sprung up in Sonic Youths shadow. Kim, meanwhile, spoke of Mariah Carey and sexism in the pop-cultural mainstream, and of her own extra-curricular work in the visual arts, collaborating with figures like Mike Kelley and Tony Oursler. Both seemed possessed of minds in constant motion, forever fascinated and energised by their own creativity, and the creativity of all those around them. Again, inspirational.

The last time I met Sonic Youth was surreal, their presence somehow comforting. I was lodging with a gang of fellow writers and photographers from Plan B magazine at a youth hostel in Stockholm, Sweden in July 2005, covering that years Accelerator festival. We woke on the morning of the 7th a little groggy from spending most of the preceding night drinking wine-and-coca-cola cocktails by the river, ordering breakfast at a nearby restaurant. As our meals arrived, our mobile phones began to buzz, carrying frantic text messages asking where we were, if we were safe. The television behind the bar was carrying footage of central London, of police vans gathered around Tube stations, injured bodies stretchered to waiting ambulances.

We were in shock, confused. None of us spoke Swedish, so the news bulletin was impossible to decipher; we ate quickly and moved on to a nearby hotel, where Plan B editor Everett True was staying (profiling Accelerator headliners Sonic Youth for a Plan B cover feature), to watch English-language news reports on his television. BBC Worldwide was playing on the lobby television when we got to the hotel; we settled on their sofas and tried to process the news of the 7/7 Tube bombings, calling home when we could get a signal, and sending emails and scouring news websites in the hotels web-caf.

Minds clouded with panic, it took a while for any of us to really notice the other tourists in the lobby. Similarly spread out across the sofas, tapping at laptops and watching the news solemnly, were the members of Sonic Youth, as concerned and as panicked and as horrified as we were. To be far from home at that moment, to feel so afraid for our loved ones back in London, so helpless, left us all sickened and unsteady. Somehow, the presence of these oddly familiar faces, who all of us had somehow looked up to from afar, like older brothers with cool music taste who only exist in a photograph on an album sleeve, was a brief but welcome comfort; to fall in amongst the warmth of the Sonic Youth family for a few moments, when we were so far from our own.

* * *

Like Walt Whitman in his Leaves Of Grass, Sonic Youth are large; they contain multitudes. They have chased inspiration in myriad directions, trawled the sonic subterranean and flirted with the mainstream (only for as long as it suited them). Check the music message-boards of the internet and youll discover riotous debate over just exactly which of their many releases, their shifting phases, is best, a discourse that never reaches a consensus. Their music threatens and soothes, toys with recognisable rocknroll tropes or throws out all the clichs in favour of noise thats entirely new.

This book is a sincere attempt to make sense of all these contradictions, of all that the group has reached for and achieved, a chance to tell the story of a band that has traced an entirely wilful and idiosyncratic path through rocknroll. The book also explores the pop cultures that have influenced Sonic Youth and the noise they make, and examines the colossal impact they in turn have made upon modern rock music: their influence, how they wield it, and how this power sits with them. Its also a celebration of a series of records and videos and live performances of a group that has spent over 26 years engaged in furious, productive and enlightening self-expression, building a canon of noise subsequent generations hold as sacred.