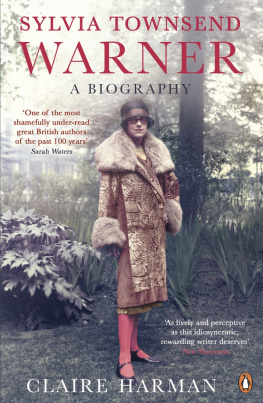

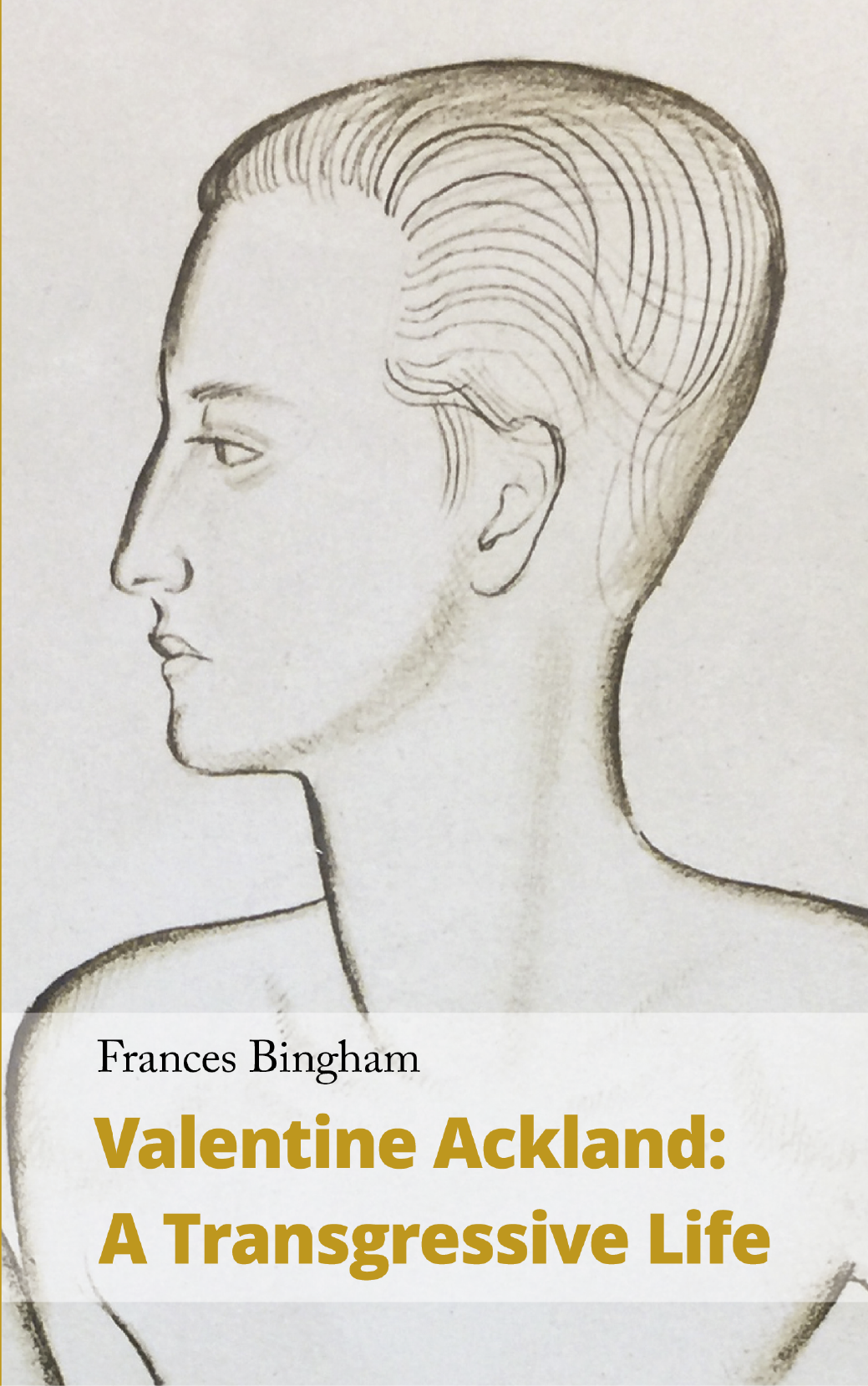

Valentine Ackland

Also published by Handheld Press

HANDHELD RESEARCH

The Akeing Heart: Letters between Sylvia Townsend Warner, Valentine Ackland and Elizabeth Wade White, by Peter Haring Judd

The Conscientious Objectors Wife: Letters between Frank and Lucy Sunderland, 19161919, edited by Kate Macdonald

A Quaker Conscientious Objector. The Prison Letters of Wilfrid Littleboy, 19171919, edited by Rebecca Wynter and Pink Dandelion

Valentine Ackland

A Transgressive Life

Frances Bingham

This edition published in 2021 by Handheld Press

72 Warminster Road, Bath BA2 6RU, United Kingdom.

www.handheldpress.co.uk

Copyright Frances Bingham 2021.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

ISBN 978-1-912766-41-3

Series design by Nadja Guggi and typeset in Open Sans.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Short Run Press, Exeter.

Dedicated to my dear mother

Caroline Bingham

19381998

Historian and Biographer

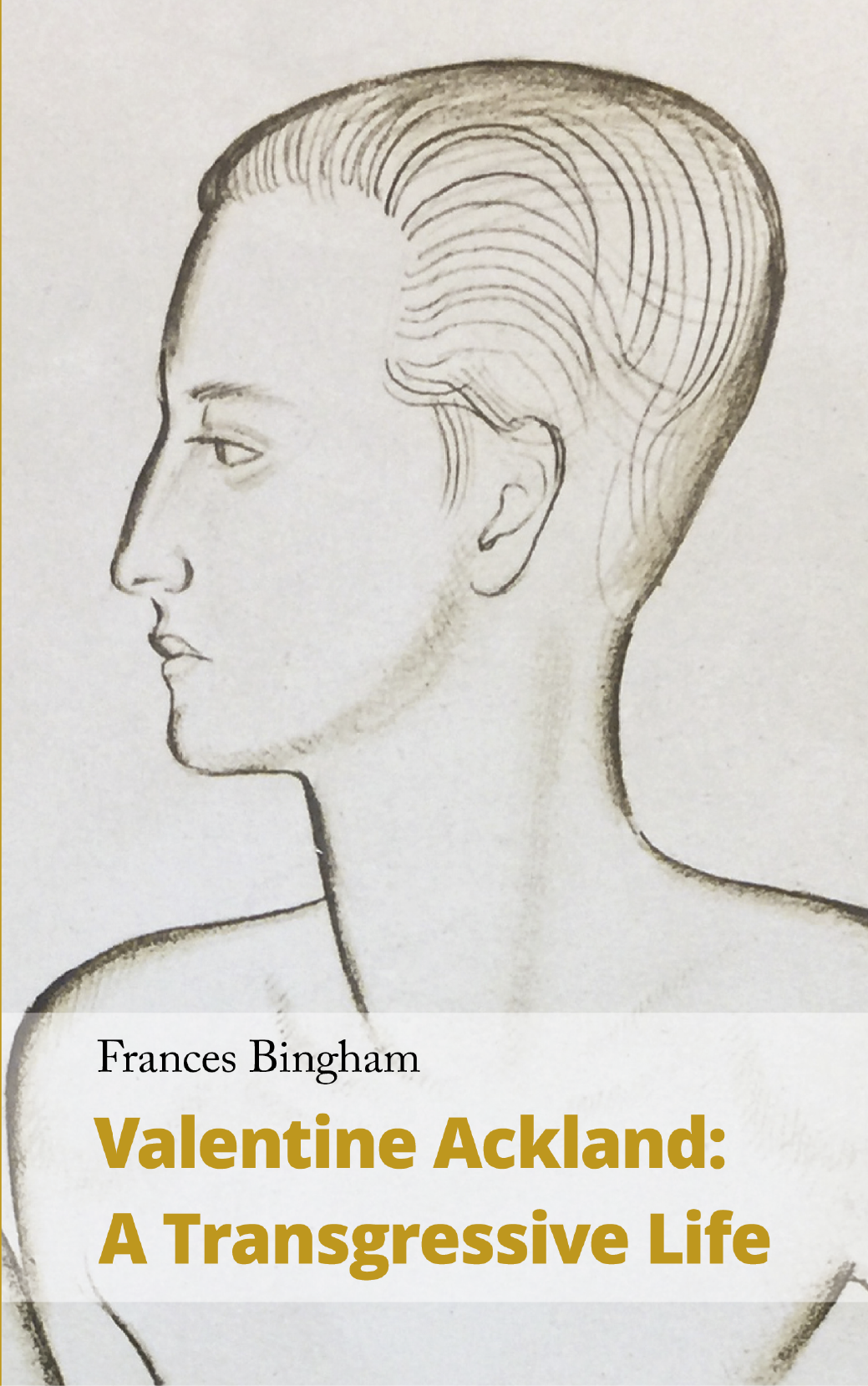

Illustrations

.

Contents

Frances Bingham writes across the literary spectrum, focusing on gender-transgressive lives like her own. As well as editing Journey from Winter: Selected Poems of Valentine Ackland, she has also published fiction, plays, and poetry, including MOTHERTONGUE, The Principle of Camouflage, The Blue Hour of Natalie Barney (Arcola Theatre, London), Comrade Ackland & I (BBC Radio 4), and most recently London Panopticon (with images by Liz Mathews).

Introduction: It Is Urgent You Understand

Valentine Ackland, poet and inveterate self-mythologising autobiographer, is best-known for cross-dressing, and being the lover of Sylvia Townsend Warner; she was proud of both attributes, but saw herself firstly as a poet. Her life encompassed Communism and Catholicism, war-work and pacifism, a life-partnership and many affairs, and above all the contradiction of being a fine poet and remaining little-known. Even if she hadnt written, Valentines life would have been a remarkable one, representative of that extraordinary generation in Britain whose intellectual maturity coincided with the mid-twentieth century, and who rose to the challenges of that time with such verve and courage. But she did write: poetry of witness, commenting on the political state of the world and the plight of the powerless individual; poetry celebrating the natural world while lamenting its loss to the encroachments of war and progress; love poetry of passionate complexity, and metaphysical poetry which meditates on the human place in the universe. This writing, by a poet deeply connected to her time and committed to interpreting its events and their impact on her own life, gives that life another dimension. Valentines work expands the history of one fascinating individual into that of a wider community.

Her own life Valentine saw as a story; she retold it to herself and others, in its various versions, almost obsessively, as though without narrative to sustain her she might vanish, become merely a blank page. Some autobiographers can swing like a spider on their linear plumb line, the straight story of their life so far; others circle earlier events at an ever-greater distance, rounding outwards like an ammonite growing. Valentine was the hermit-crab variety, carrying her past everywhere, embellishing it and inhabiting it, using it both as camouflage and display, yet ready at need to jettison it for a similar, larger version of heavy identity. Her willingness to shape her life story to different artistic ends, and the parallel text of her poetry (not explicitly autobiographical, but a translation of experience) makes writing her biography an unusual task.

The outwardly significant events of her life, their places and dates, are well-documented through multiple evidence, and duly appear in this book. The detailed record of an inner life, a writers creative narrative, is also here, often in Valentines own words. Autobiography offers insights (both intentional and unintentional) to the writers mind, the colour of her thoughts, the weather of her relationships, which is why Ive quoted so extensively from Valentines writing on herself. She was well aware that her diaries were revealing, of her weaknesses as well as her humour and passion. Once, after quoting something self-complimentary she added Of course I ought not to copy this, but no one will know until after Im dead, if then, so what odds? This throwaway remark could be taken to apply to her entire life-writing oeuvre, so much of which is about her work, as well as the sometimes dramatic events of her life.

As Virginia Woolf ironically observes, in a frequently-quoted passage from Orlando: life is the only fit subject for novelist or biographer; life has nothing whatever to do with sitting still in a chair and thinking this mere wool-gathering; this thinking; this sitting in a chair day in, day out, with a cigarette and a sheet of paper and a pen and an ink pot. If only subjects, we might complain (for our patience is wearing thin) had more consideration for their biographers! And she completes the faux-diatribe by declaring that, as we all know, thought and imagination are of no importance whatsoever. And yet, in Orlandos life, as much as in Valentines, the invisible inner life of thinking and writing is as eventful as the outer life of action.

Apart from her books and (many but scattered) magazine publications, Valentines writing has been preserved in the Sylvia Townsend Warner Valentine Ackland Archive. When I was first researching both authors, these papers were still in Dorchester Museum, housed in an attic lined with oak cupboards a haphazard treasury; part library, part paper-heap. There are dozens of notebooks, ranging from large ledgers and leather-bound account books through diaries of every size and format to tiny memorandum books for the pocket. All of these are crammed with poems, both finished and unfinished (some in many versions), notes, quotes, diary entries, travel journals, accounts, lists, reminders, prayers, jokes, menus, fragments of ideas. There are also shopping-lists, used envelopes, telephone message-pads, old photographs and post cards, with poems scribbled on the back. The history of a writers mind is here. There are many boxes and files of typed paper: short stories, articles, a play, a novel or two, a childrens book, the poems and of course memoir and autobiography in many versions and revisions. Some of Valentines writing is not represented in the archive at all, some pieces are duplicated many times.

Also in the archive is the mirror-image of all this; Sylvias papers, just as varied and unchronological, often telling the same life story from the opposite viewpoint. There are also innumerable mementoes of a shared life: love-letters, Christmas cards, notes, postcards, telegrams, their hotel room reservation card for Mr and Mrs Ackland. There is an intense immediacy about these relics. The notebooks are covered in tear-stains, cigarette-burns, cats paw-prints, wine or coffee splashes; full of pressed flowers, dried leaves, cuttings and scraps, the feathers which Valentine picked up and kept, as they symbolised to her descending poems. The books smell of the river which ran past their damp house, the ghost of Gauloises cigarette smoke, the vanishing trace of scent from the writers wrist. On opening one of the rarely-disturbed oak cupboards, one was assailed by this fragrance of the past, slowly fading in the attic of a museum.

Next page