Also by the author

Love and War in the WRNS

Contents

When he was good he was very, very good, but when he was bad he was horrid

(with apologies to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow)

Something to laugh at and something to make you cry thats what I like best

Tomy Ungar, aged 5, from Tomy Helps to Write by

Hermann Ungar

For all my family, dead and alive

but especially for Louise, Tommy, Sasha and Bonnie: this is your story

FOREWORD

Dar es Salaam 1963

I was about five or six years old when we met the new Czech Ambassador. Ill teach you how to say hello to him in Czech, said Dad. With great aplomb I marched up to him and said, Vilis mi prdel . The Ambassador gave a huge guffaw and my father was almost beside himself with glee. Whats so funny? I asked. Ha-ha-ha, he chortled, you just told the Ambassador to kiss my arse.

Who was this man who could play such a childish and cruel joke on his daughter? At that time my father was permanent secretary for foreign affairs in the newly independent Tanganyika. But he was much more than that. I was an only child and Daddys girl and remember my father as the largest person in my life, dwarfing my mother with his absolute devotion and the way he spoiled me.

He encouraged me to collude with him against her I was instructed not to tell when he let me drive the car sitting between his knees, or when we made a fire in the middle of the game park and had breakfast surrounded by herds of buffalo, or when we visited my various nice aunties when my mother was sick with TB.

My parents had met in Germany in 1945 at the end of the war; he was attached to Royal Naval Intelligence in Kiel and she was a Wren. They married in Durham in 1946. Dad was an idealist who had become a self-confessed socialist during the war and wanted to make the world a better place. But his public persona was in complete contrast to how he lived his private life and dealt with his family. As I grew older I found it increasingly difficult to understand how this outwardly altruistic character could coexist with a father who was not the man he appeared to be, but was, rather, bad-tempered, cruel and sometimes violent. It was only when he retired from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 1997 that I began to examine these contradictions.

By then I felt sorry for my father. His days consisted of reading The Times and the Daily Telegraph and writing letters to the editor, usually about the politics of development or pertinent issues of the day. He relished complaining to phone companies and other service providers, often masquerading as Admiral Unwin he found that produced results and enjoyed walking his dogs. After they died it appeared to me that he did nothing but sit in his study in The Fort, his Somerset home; and then in 2001 he developed Parkinsons, his legs black and bloated with cellulitis, his hands and speech shaky.

Long since divorced and remarried, he still visited my mother now and then. She lived in neighbouring Devon and, despite all the lingering acrimony between them, they would reminisce about old times and mutual friends over a good East African fish curry, prepared by my mum. Like me, my mother just could not understand how such an active and intelligent man could sink to such depths of depression and introspection.

By this time it was obvious to me that my father was not the man everyone called good old Tom, the perfect Englishman, former colonial officer and UN diplomat, with his pipe, monocle and received pronunciation; the handsome charmer and flatterer who was always the centre of attention at any social gathering, bursting with so much self-confidence and bonhomie that he fooled just about everyone. A man who was simultaneously the adoring father of my childhood and a misogynistic bully of a husband, whose temper and dark side alienated him from my mother, me and, later, his grandchildren. A man who was responsible for the biggest betrayal of all the betrayal of a child by their father. It was not until I began to delve into his past that the impact of his destructive behaviour and its effect on all of us became clear.

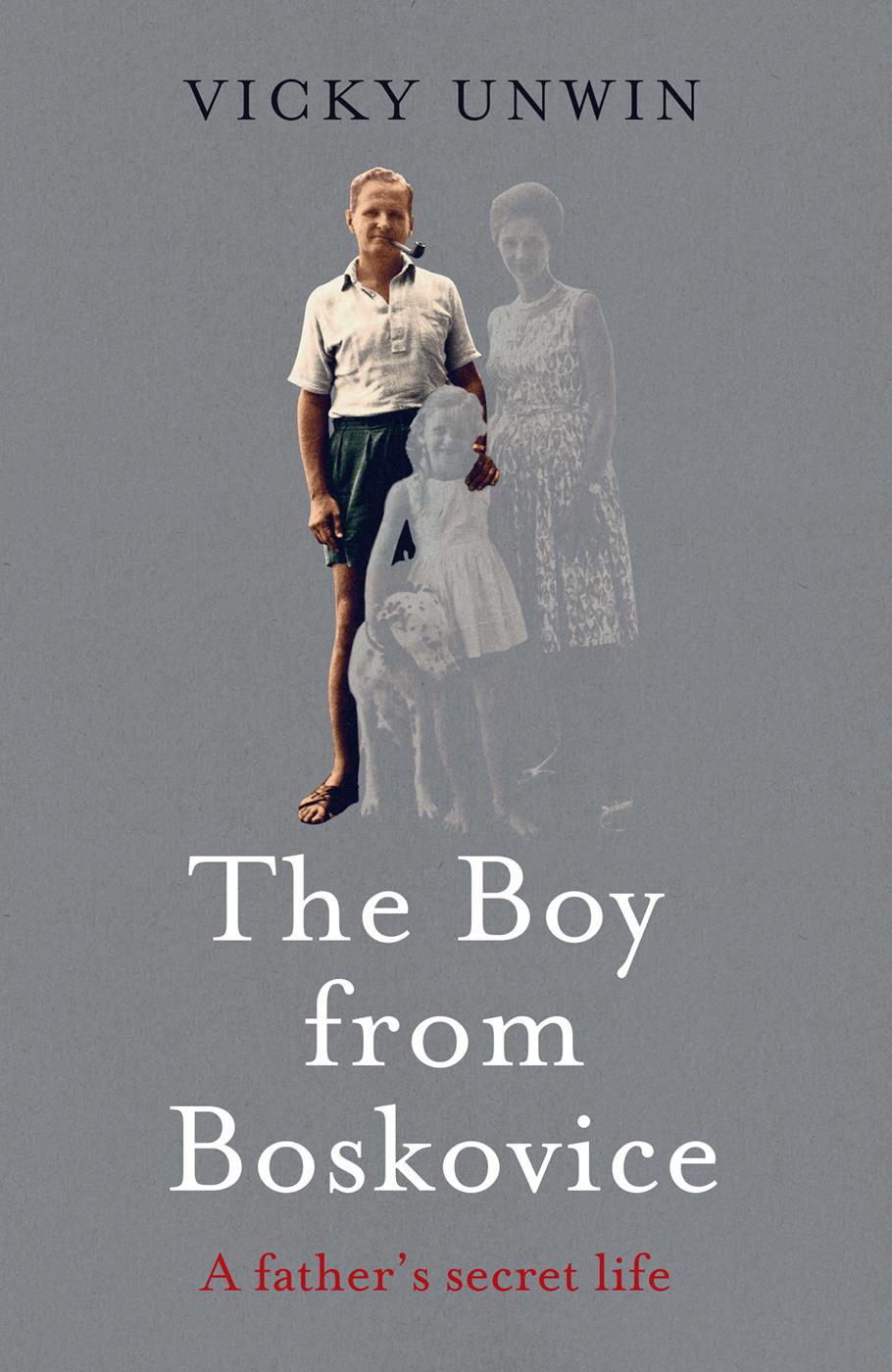

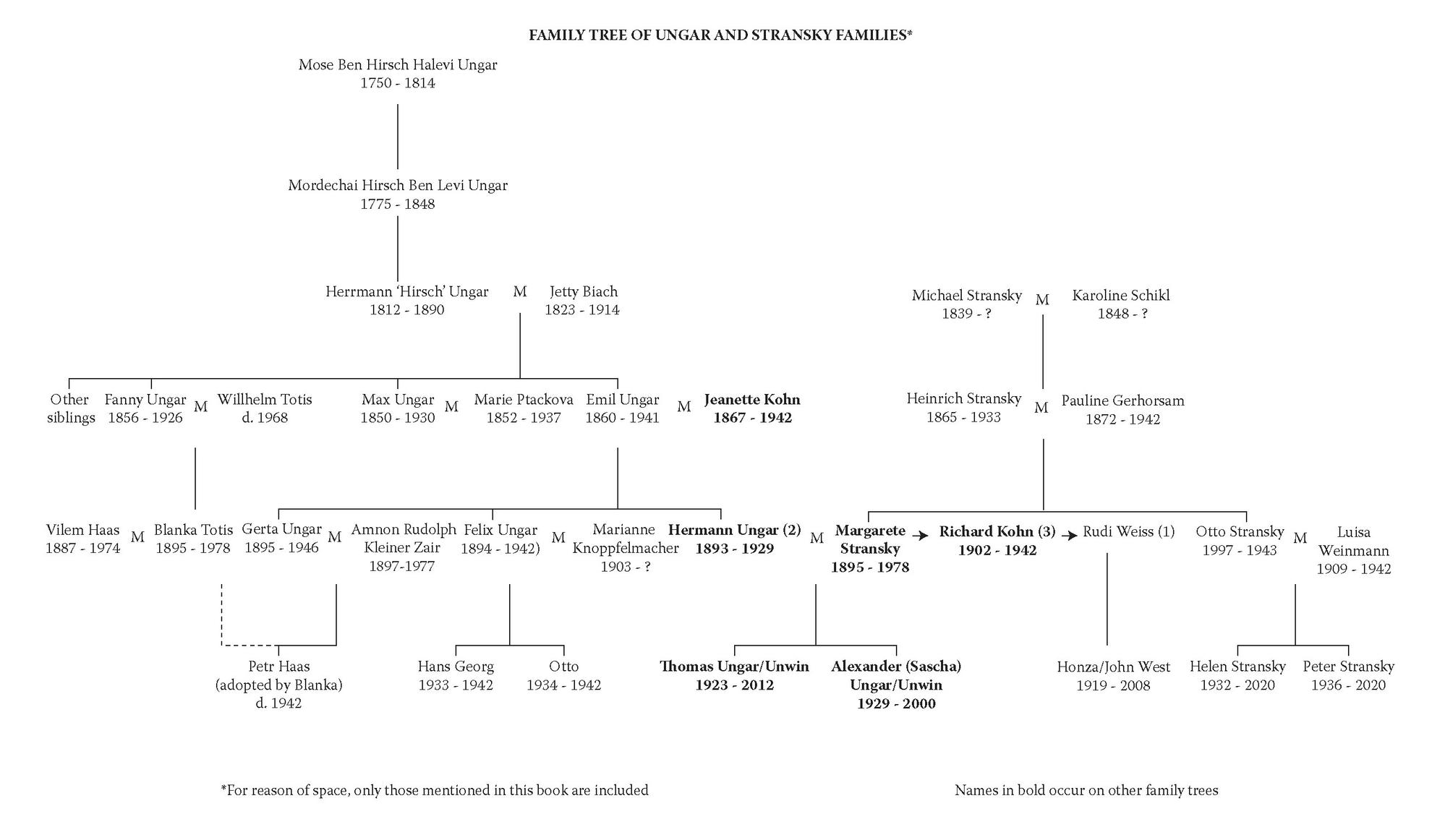

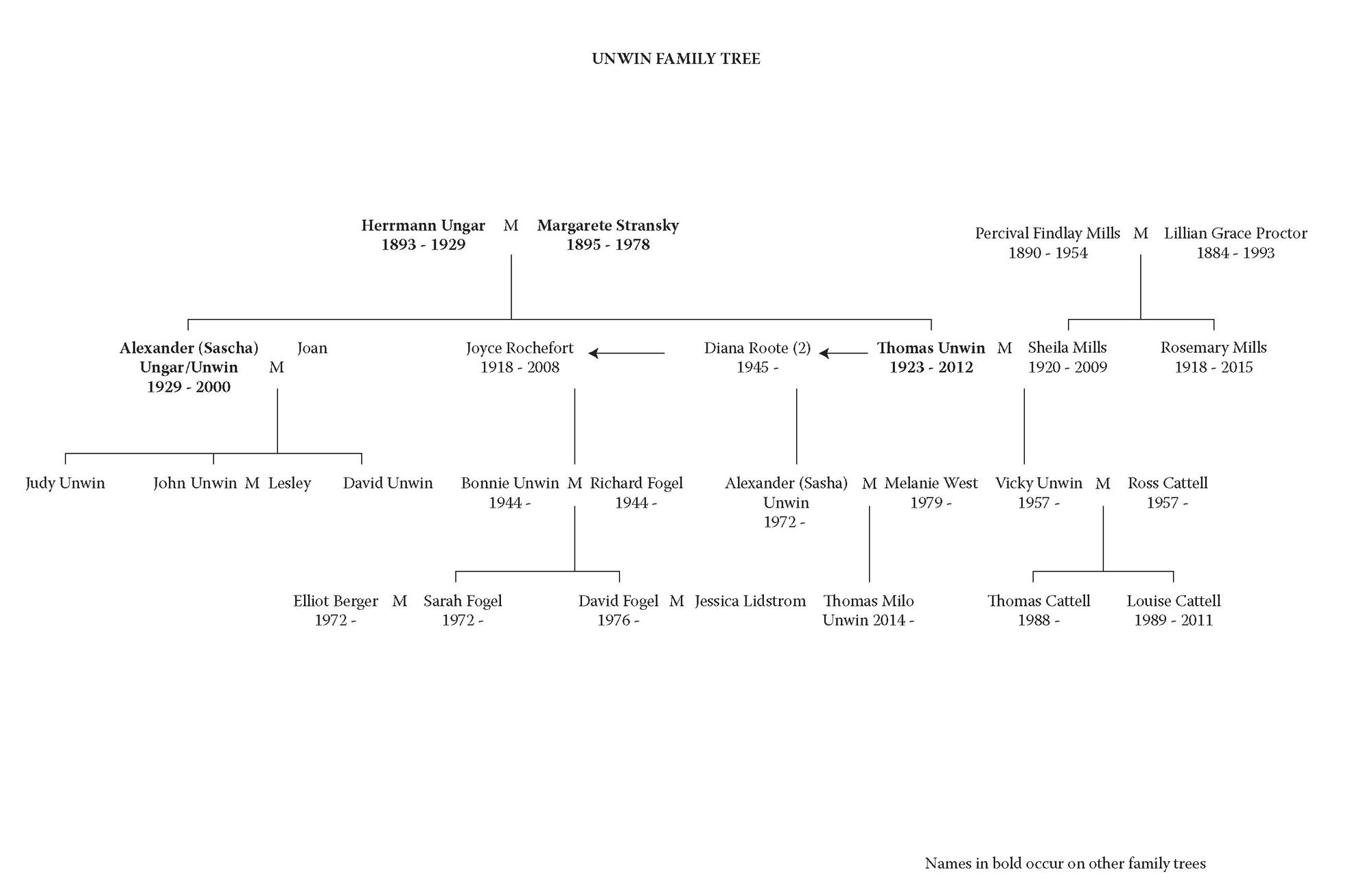

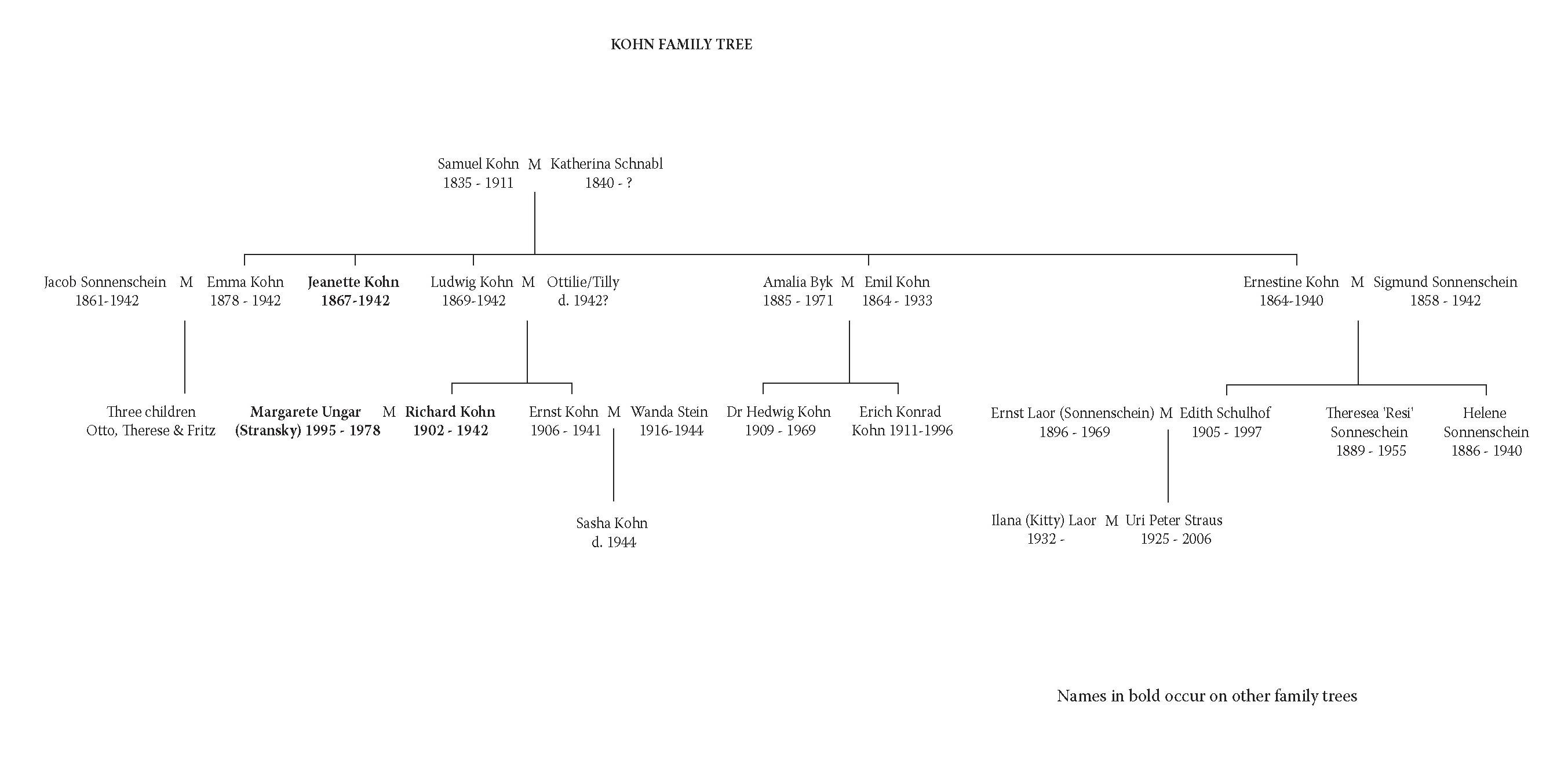

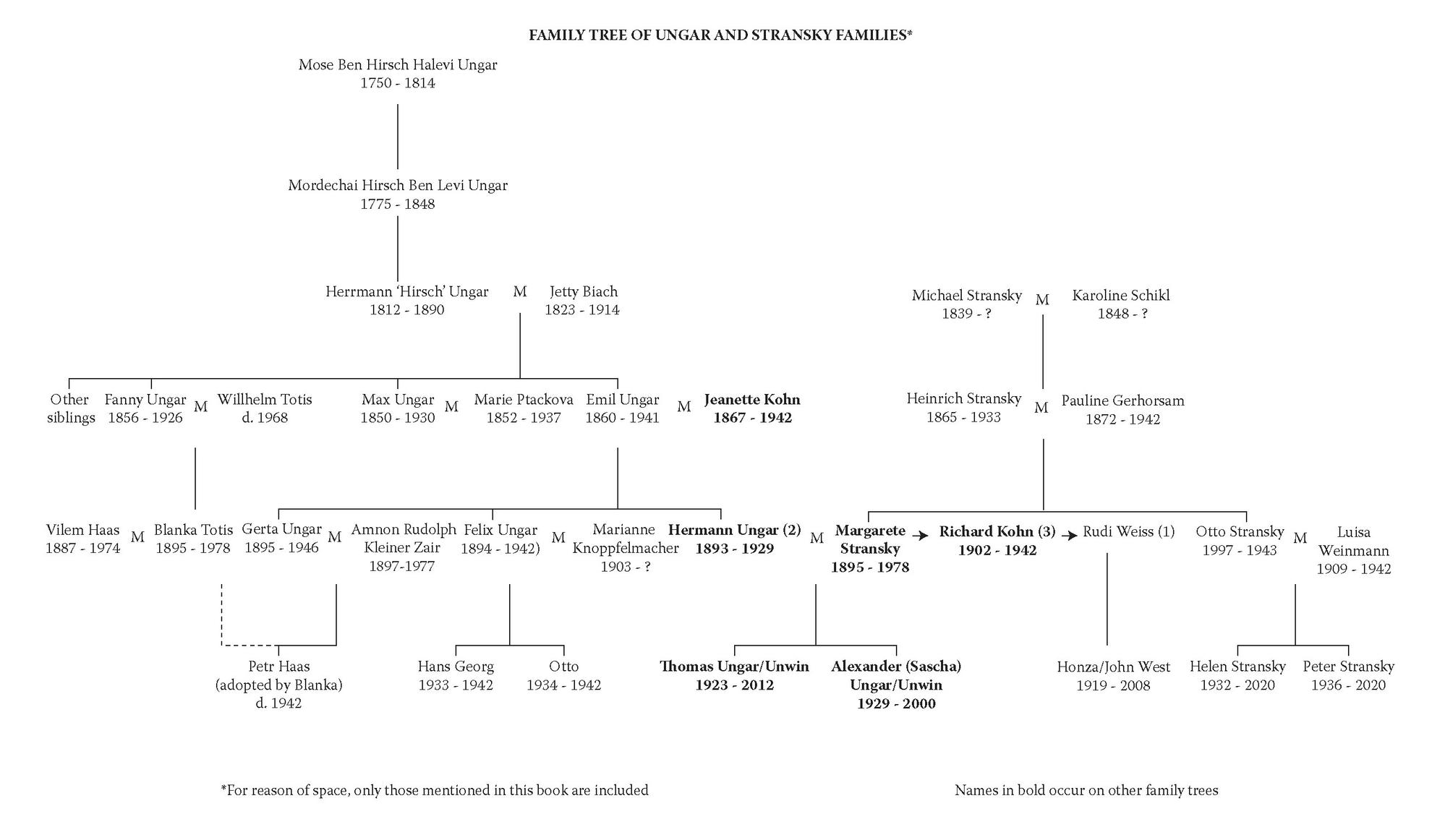

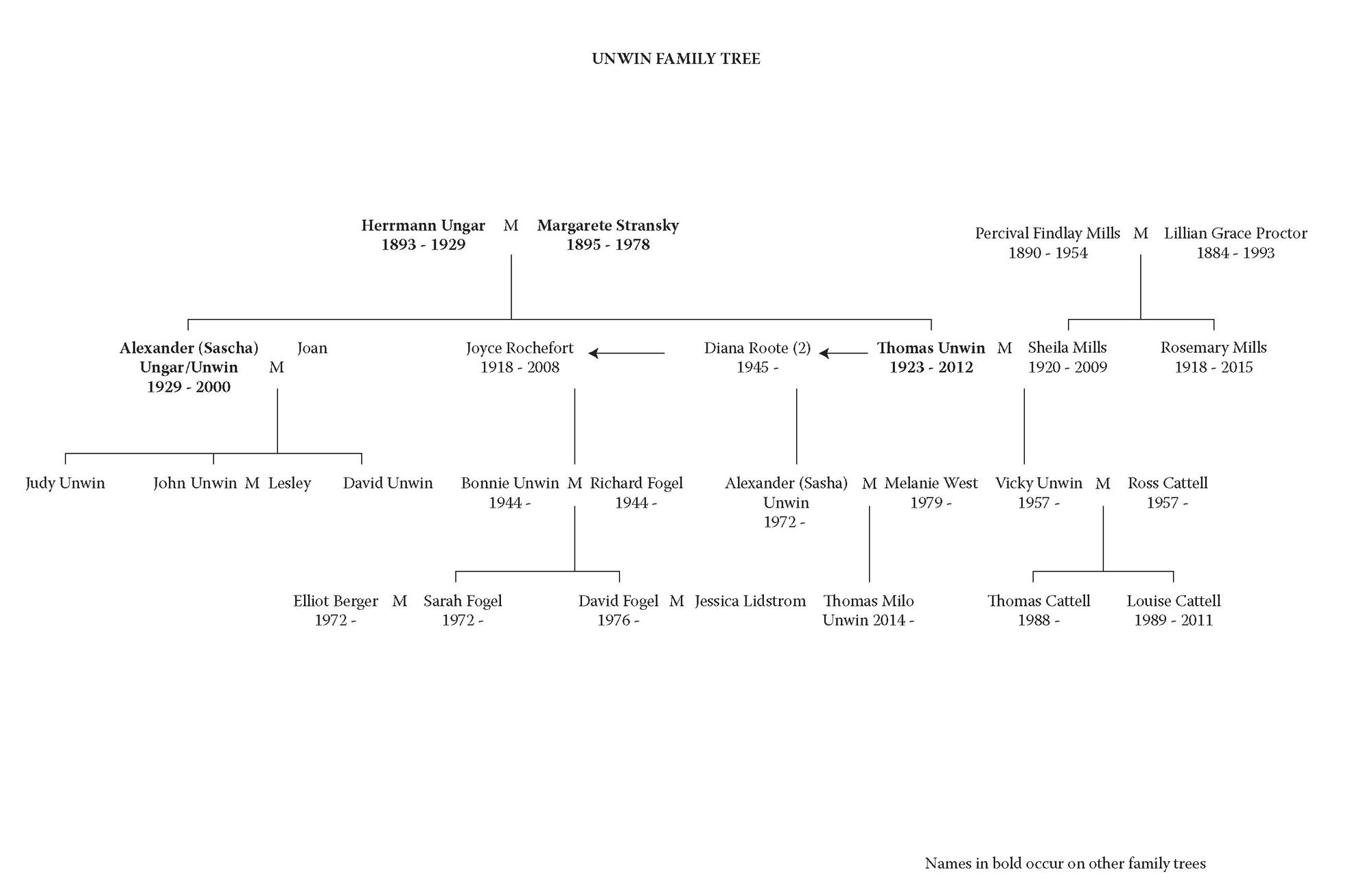

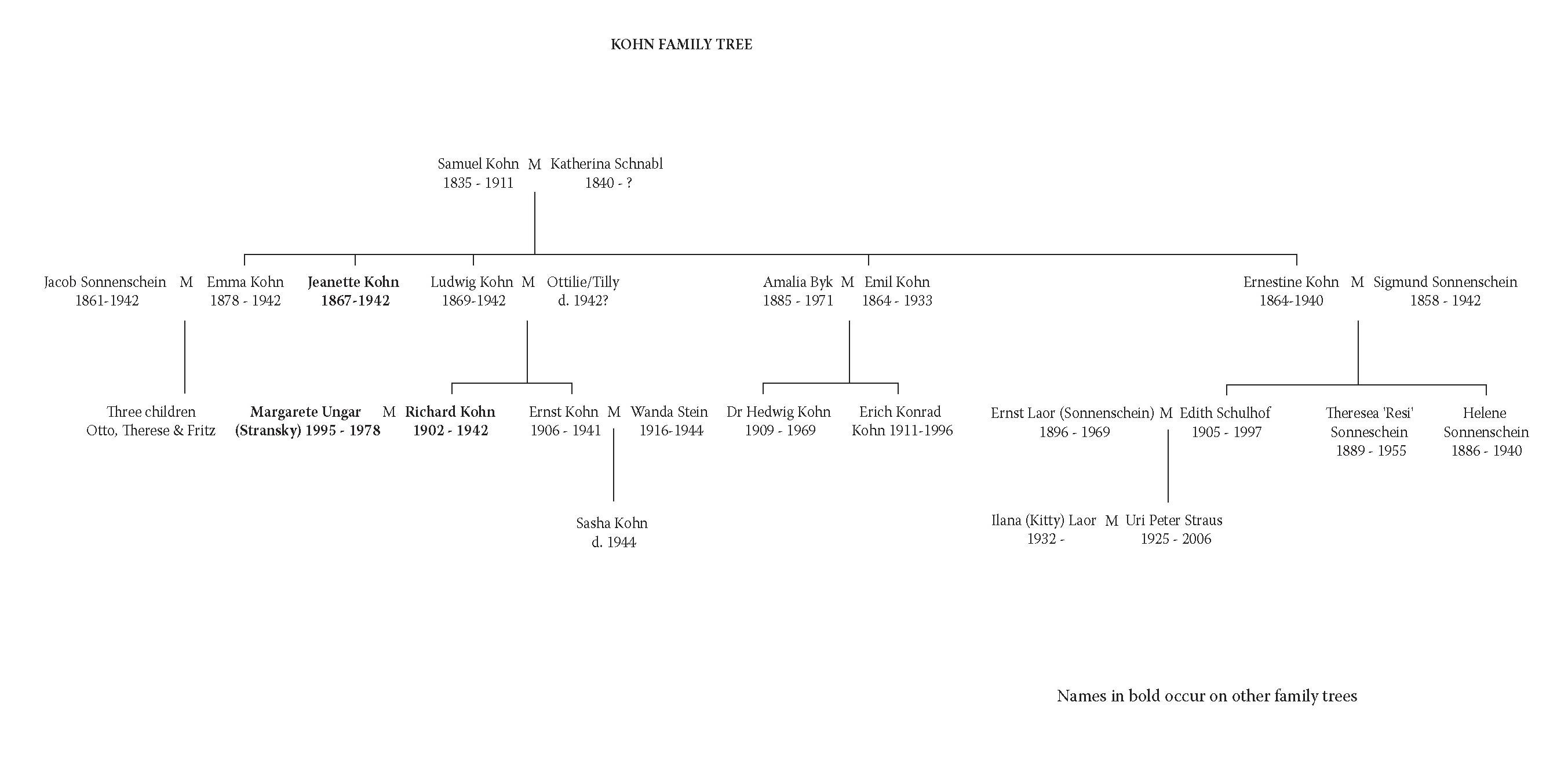

For Tom Unwin was also Tomas Ungar, the boy from Boskovice, a small town in Moravia, a teenager who left Czechoslovakia shortly before the Second World War for a new life and a new identity in England. The young man who became Tom Unwin and achieved a very British respectability by denying his roots and abandoning his family until his past caught up with him.

Part 1

Who was my father?

CHAPTER 1:

NOT REALLY BRITISH AT ALL

I was born in 1957 in Dar es Salaam, the capital city of what is now Tanzania. When I was five my father took me to an amateur performance of The Bartered Bride by Bedich Smetana, the father of Czech music , at the Oyster Bay Primary School in Dar. It was then that he first told me I was Czech and that our real name was Ungar. I was so taken with the show that I began to call myself Maenka after the main character and told my father I would change my name back to Ungar when I was grown up.

That was the sum total of my knowledge about my fathers origins and it was to take me decades to unravel his history.

Tomas Michal Ungar was born in Prague in 1923, the son of a Czech diplomat and rising author Hermann Ungar, whose family came from Boskovice in Moravia. My pride and joy is my son Tomas, Hermann wrote, and he brings his little boy to life in 1929 in a short story called Tomy Helps to Write, first published in 1929 in the Prager Tageblatt ; this is my fathers translation that I discovered among his papers:

Tomas, known as Tomy, five years old, has written a story to help his father. Father complies with Tomys wish and sends the story to a paper for grown-ups. But one wish of Tomys Father cant comply with: Tomy asks his father not to say who wrote his story: If they know its written by a little boy, they wont pay as much.

I make use of the opportunity to tell you something about Tomy just as it comes into my head. Tomy is just like other children of his age who are healthy and normal.

So: Tomy is a little numbskull on whom any attempt to bring him up properly is wasted. In any case I have given up trying. I leave it to fate to decide what is to become of him. I admit openly that I envy Tomy his unyielding nature. He is not to be deflected from his aim: there is no bending, no being-got-down, nothing stops him doing what he has made up his mind to [sic]. A little while ago I heard an infernal row coming from the nursery, not the usual daily row, and I knew at once this was something special as I heard the sound of breaking glass. I rushed to help. I saw immediately, without waiting to ask questions, what was up. He was cross at being disciplined by his superiors and so my ever hopeful son smashed the pane of a glass door with a building brick. Without saying a word I put him across the table. I was as furious as only a grown-up can be and beat Tomy accordingly. I only interrupted this educational process to catch my breath and to ask my son, Will you do it again? The little one replied, steadfast to the end, time and time again, Yes! His eyes were full of tears but he suffered the execution without uttering a sound. And as he rightly I fear does not take me seriously as an educator he had forgiven me my folly by the time I had finished beating him.