Jacket copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All interior photographs courtesy of the John Bolger Collection.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com . Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

Classical, jazz, rock, country, blues, rhythm and blues, bluegrass, avant-garde, hip-hop, contemporary classical, modern classical, modern jazz, free jazz, fusion, electric jazz, freeform country, world music, island music, standards, film music, alternative rock, indie rock, folk rock, grunge, punk rock, psychedelic rock, post-rock, garage rock, math rock, progressive rock, pop, electropop, electro swing, Europop, Britpop, power pop, Latin jazz, bebop, EDM, trap, dubstep, house, lo-fi, alternative R&B, rap, mumble rap, soul, funk, folk, reggae, metal, heavy metal.

On and on (and on), as the years advance, the music changes, cultures change, all things change while we continually attempt to describe the music and art we make. We need to talk about it. Its an essential part of lifea basic and native sense to be artistic, create something beautiful, have art in our lives.

We try to explain to others what music is; encourage them to understand. As musicians and artists, we want them to get itto participate. We inherently know that tuning up to the wavelength of art and creativity will bring benefits, will make life more enjoyable, lift the spirits.

The talk and discussion about music and art comes in all formsbut basically two: friendly with a high interest and critical. Mostly, the artists and public converse with friendly high interestwhereas youll find the critical approach in the media and in schools and universities.

Personally, I have found the only way to understand and appreciate music and art is to touch the artists making it. To listen, to look, to experience, and, best of all, to do.

Dave and Iola were an amazing couple. My sweet wife, Gayle, and I had the pleasure of visiting them in their Connecticut home one time. They had an ideal relationship as man and wife and as artistic collaborators. Very similar to Gayles and my life together. They were a big inspiration to us.

As the years and decades rolled on, my appreciation for Dave and for his compositions, bands, and piano playing increased as I listened and experienced his dedication and commitment to creating his music. In the 1970s, when the term fusion was invented to negatively describe Return to Forever, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, and Weather Report, I realized that Daves music was an early breakthrough well before the 70s. That combination of composed and improvised music forms was well under way in his creative hands. The musicians and artists were combining more influences from other parts of the world and other cultures. The artists were sharing their ideas more quickly. Dave was a pioneer and an innovator.

My memory of playing Strange Meadowlark at Daves memorial, with Iola in the front row with the whole Brubeck family, is a beautiful spiritual moment I wont ever forget for the love that we shared in that great cathedral for Dave.

Words are simply inadequate to describe music and artor Dave Brubeckunless you are a poet.

I and the music world are forever thankful for Daves reverence for creativity and irreverence for categories.

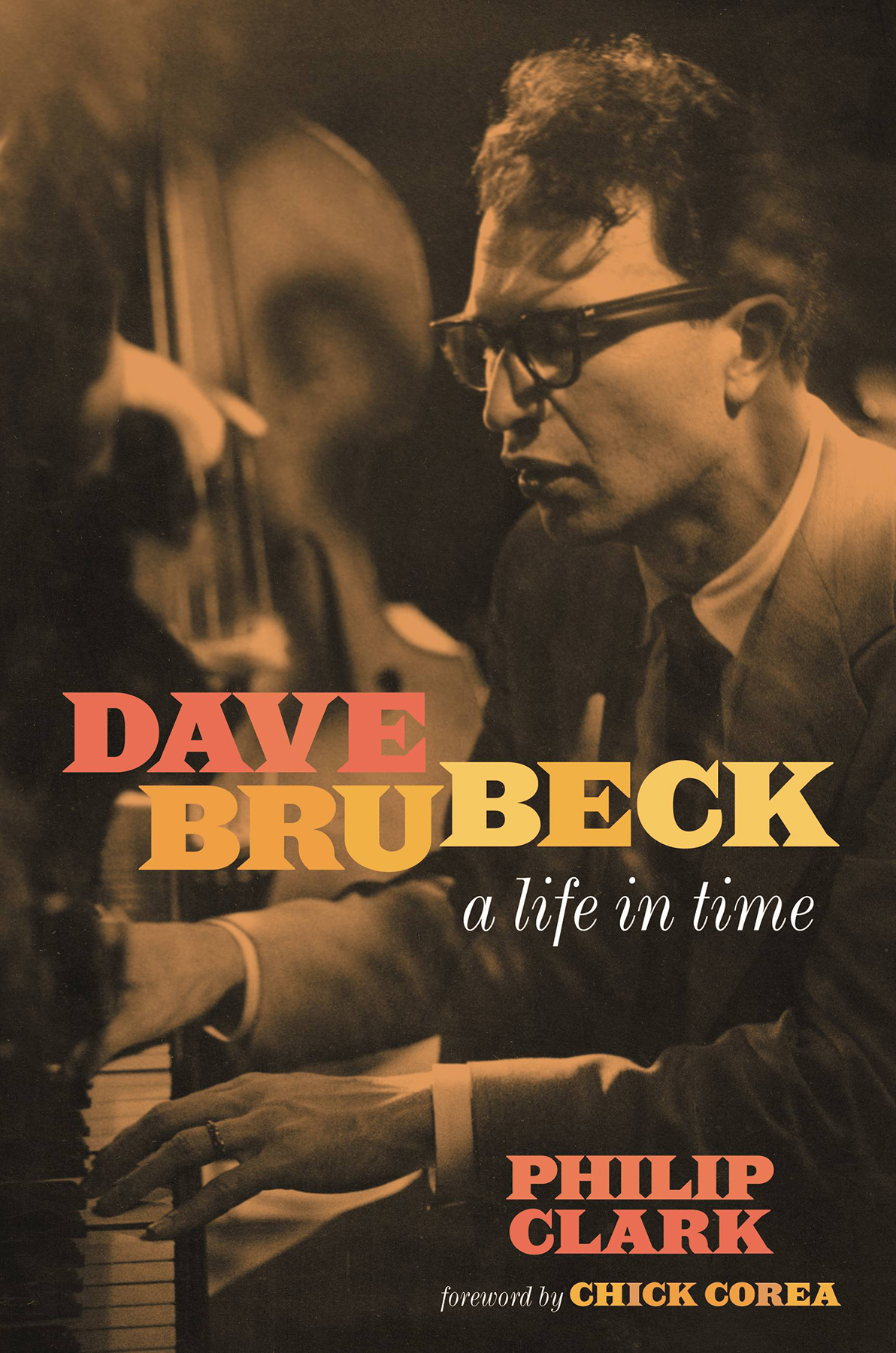

C HICK C OREA

November, 2019

Once I had my title, not writing became more of a problem than sitting down to begin.

A Life in Time was a title that encapsulated the classic biographical model of the life and times, but it also opened up the terrain. The project was not to write a book that marched through Dave Brubecks life chronologicallycasually observing, perhaps as an aside, that shortly after his quartet recorded Take Five in 1959, Vice President Richard Nixon flew on a trade mission to Moscow and Billie Holiday died. The plan instead was to thread his life back through the times that formed it. Brubeck saw active service as a solider during the Second World War; he led a commercially successful, racially mixed jazz group during some of the ugliest days of American segregation; and in the late 1960s and early 1970s he created a series of large-scale compositions that reflected variously on issues of race, religion, and the messy politics of an uncertain era. Threading his life back through these times was both a musical and a social concernI wanted to shine a light on how Brubeck, thoughtful and sensitive as he was, had been changed as a musician and as a man by the troubled times through which he lived and during which he produced such optimistic, life-enhancing art.

As a biographer in search of a title, I was handed a gift by Brubeck, even if it took me a while to realize it. He was a man obsessed with time. From the moment he founded the Dave Brubeck Quartet in 1951 to only eighteen months before his death at the end of 2012, Brubeck spent much of his life touring the world, which adds up to sixty years of playing concerts in every continent of the world, including some countries that today would be too dangerous to contemplate visiting.

He was also a man impatient with time. Finding time to play jazz, time to compose, and time to devote to his wife Iola and their six children were all important to Brubeck, and with only so many hours in the day, one solution was to overlap those activities. Compositions originally written for his extended sacred pieces were adapted for his jazz groups; and, if you want to spend more time with your teenage children, one sure way to know where they are every night is to play jazz with them. Beginning in 1973, Brubeck toured with three of his sonsDarius, Chris, and Danas Two Generations of Brubeck and the New Brubeck Quartet, his initial reluctance to embrace their newfangled cultural reference pointswhich included rock, funk, and soul musicquickly forgotten.

But that word, time, also had another meaning altogether. Whenever I interviewed Brubeck, it never took long for two key terms to emerge: polytonality and polyrhythm. Polytonalitymusic sounding in two or more keys simultaneouslyand polyrhythmoverlays of different rhythmic pulses and grooveswere, like the attitude he took toward life, techniques that allowed obsessions and tics to coexist. Brubeck plied his music with overlaps: between musical cultures in Blue Rondo la Turk, which combined an indigenous Turkish rhythm with the blues, and in Three to Get Ready, which squared the circle of a waltz by inserting bars of 4/4; between different time signatures, like his version of Someday My Prince Will Come, which managed to be in 4/4 and 3/4 at the same time; between the radically diverse range of musical styles through which he waded in his improvised solosno sweat as Liszt flowed into James P. Johnson.