ONE DAY

All the flowers that Ive picked

all the shells from the sea

can never ever equal the love you gave to me.

Now as I stand upon this empty shore

Im wishing for your arms

they cant hold me anymore.

All the scrapes and bruises

the long teary nights

you comforted and guided me

taught memade mestand up and fight

Now you can rest your tired and weary soul.

Your spirit soars with the sky

you have stars to hold

When the wind whispers, and the moon guides my way

Ill fall to my knees asking your Angel wings

to lift me upbe with youand pray

Together againONE DAY.

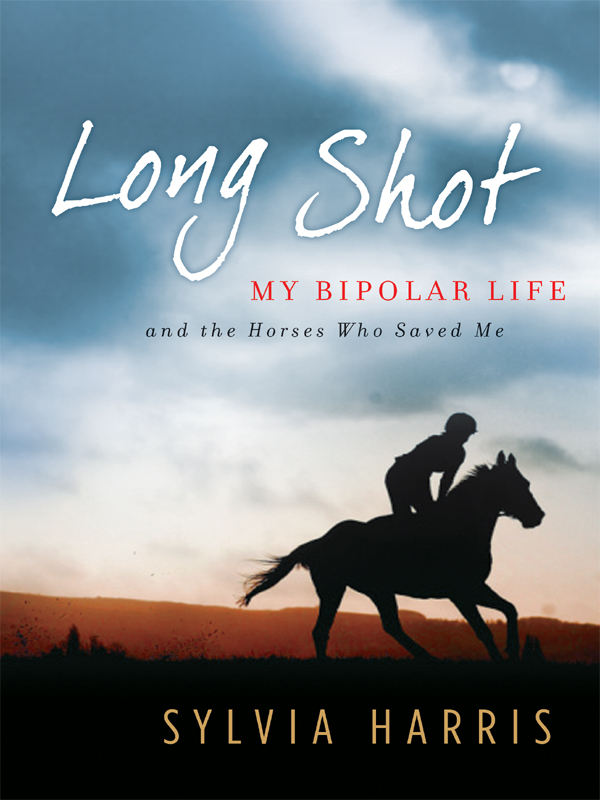

I am small in stature, barely an inch above five feet. But I can put up a good fight, something Ive been doing all my life, often with family, friends, and strangers but mostly with myself. I am bipolar and have struggled with it since it surfaced shortly after high school. I ascend to heights of frenetic energy and confidence only to plummet to hellish depths of madness, guided by unseen voices and terrifying hallucinations. Imagine youre watching a DVD or a video, and you pick up the re-mote and punch fast-forward. Suddenly, those images flash by in milliseconds. The screen of my mind operates in the same fashion. It is in manic phase when I sketch voluminous drawings of people, places, horses. And Ill sketch them on anything: paper, napkins, walls, wherever I can create. If Im not sketching, Im writing volumes and volumes of poetry or prose with unchained thoughts in my journal, until finally I crash into days of sleep. It is exhilarating while in it, but exhausting coming out of it. More than once Ive found myself within the confines of mental institutions, and many more times Ive gone off the deep end after tottering on the edge of reality and fantasy, unable to maintain my balance against a whirlwind of raging emotions.

Im forty-three years old, but my life feels twice that. People say I am an angry woman. I am. When youve had to fight through so many things, its hard not to be. I have been hungry, cold, abused physically, tormented emotionally, homeless, and frequently out of control. But Ive also, at times, lived a seemingly quite normal life with my three children and their father. And against all odds, at forty years old, I became the first African American woman in Chicago racing history to win a race and only the second in U.S. history.

I continue to struggle with being bipolar and always will. But psychotropic medicines, which have not always been available to me, spiritualism, which in my case happens to be Buddhism, andmost importantmy love of horses keep me from looking at life as one continuous battle. My life has been a race to outrun the disease that attempts to consume me. To that point, I tell my story in parallel to my biggest race, that cold day in December 2007.

I havent always been able to live life on my terms, but Im optimistic Ill get thereeven if it is a long shot.

Sylvia Harris

July 2010

Hawthorne Race Course

Cicero, Illinois

December 1, 2007

I n an empty stall, at a makeshift altar, I close my eyes and begin my Buddhist chant, Nam-myoho-renge-kyo : Devotion to the teaching of the mystic law of the universe, or even more loosely translated, Devotion to cause and effect. I chant to quiet my mind in a way that lithium or Haldol cannot. Then I get dressed and head to the paddock.

December in Chicago is brutal. On this snowy Thursday evening, a cold front from Canada is blowing snow and ice into the city, creating dangerous conditions. As I pass through the backstretch, also known as the backside, an area of stables and living quarters for the people who call the track home, little ice pellets stab me in the face, but I dont really feel it. My mind is on Peg. We have a lot in common, Peg and me: a broken horse and his broken rider. He was sired by Fusaichi Pegasus, who won the Kentucky Derby in 2000, a promising mount that never materialized, and I was the all-American girl from Santa Rosa who had long ago lost her way.

Wildwood Pegasus is a four-year-old gelding who has lost his spirit, but I understand him. When you spend time in and out of mental institutions, questioning your reality and making a mess out of your life, your spirit takes a beating that no anti-depressant or mood stabilizer can fix. Pegasus is arthritic, with a bum right leg shattered during a practice run when he was a promising two-year-old. Together, we are a bad bet. Entertaining, maybe, but a bad bet nonetheless.

When I reach the paddock, he is waiting for me. Jockeys can be superstitious. Many have rituals before or after every race. British jockey Graham Thorner wore the same underwear for every race he won after winning the Grand National in 1972. They got so old and frayed that he would wear a new pair over the old ones until he ended his career. Garrett Gomez, one of horse racings biggest prizewinners, makes sure he steps out of bed with his right foot first on race day; and top jockey Ramon Dominguez reads a quote from Booker T. Washington thats taped to his locker before every race: Success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has overcome. Me, I have two rituals. I chant, and then, before I mount the horse, I breathe him in . I know it sounds a little Horse Whisperer -ish, but when I breathe in a horse, its as if we are kindred souls. We are one.

I hold Pegs face in my hands and press my own to his, to breathe my baby in. So there we are, Peg and me, nose to nose; soul to soul. Peg, my beautiful Peg, I said. Tonight, its youyou show me. Im just along for the ride.

I gulp down the freezing air near the paddock as both of Pegs trainers, Charlie and Janelle, come over. Their bright, sunny smiles greet me, and suddenly everything is more than fine. The three of us stand in the cold with a light snow falling and with that beautiful smell of horses filling our noses. We have been working with Peg for weeks, and we instinctively know this is his time. Charlie and Janelle both give me a leg up onto Peg, who waits patiently for us to finish. Once my body connects with his, there is only one way to go. As Peg carries me, I feel as if its a new day and a new life. I always feel that way when I get on the back of a horse.

Following tradition, we are led to the starting gate by the outrider, Jerry. Life on the backstretch is full of irony. Jerry, an ex-cop with a questionable past, is quite the horseman. Fit and good-looking, he has a deep love affair with cognac, and a few days before wed had a heated argument in the parking lot of a bar near the track. I dont even remember what it was about, most likely something petty, personalthats the way it can be on the backstretch, the world behind the racetrack. Its a carnival-like atmosphere filled with runaways, addicts, desperate lost souls, and the rich people who employ them. But when its time to compete, everyone does his job. Jerry is no different. He throws me a look that says, Go , Sylvia . I nod to acknowledge it.

Once were near the starting gate, I look up to the grandstand briefly to find my family. Theyre here visiting me, and for the first time, they will see me ride. I peruse the crowd until I see them looking down at me, wearing mixed looks of pride and concern. Theyre like many American families, a cornucopia of dysfunction. My father, Edward Sr., a tough ex-army staff sergeant and recovering alcoholic; my mother, Evaliene, an ex-teacher with Crohns disease who for years was a punching bag for my dad; my brother Edward Jr., the ministerlets just say hes the good one; my oldest children, daughter Shauna and son Ryan, from my common-law marriage with Riley, an Irish hippie I met at a club. And then there was Mioshi, my youngest, the baby who was conceived during a manic farewell tryst in Los Angeles. They were all there together, and for once it was not a gathering to decide, What are we going to do about Sylvia? A rare occasion.