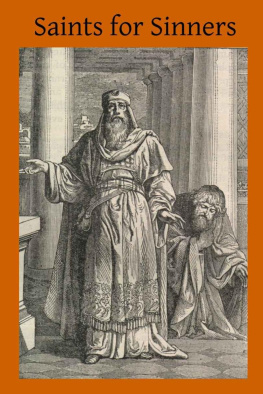

Alban Goodier - Saints for Sinners

Here you can read online Alban Goodier - Saints for Sinners full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Saints for Sinners

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Saints for Sinners: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Saints for Sinners" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Saints for Sinners — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Saints for Sinners" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Saints for Sinners

Alban Goodier, S.J.

Table of Contents

Preface

St. Augustine Of Hippo354-430

St. Margaret Of Cortona The Second Magdalene1247-1297

St. John Of God The Waif1495-1550

The "Failure" Of St. Francis Xavier1506-1552

The Self-Portrait Of St. John Of The Cross1542-1591

St. Camillus De Lellis The Ex-Trooper1550-1614

St. Joseph Of Cupertino The Dunce1603-1663

Blessed Claude De La Colombiere1641-1682

St. Benedict Joseph Labre The Beggar Saint1748-1783

The foolish things of the world hath God chosen that He may confound the wise and the weak things of the world hath God chosen that He may confound the strong and the base things of the world and the things that are contemptible hath God chosen and things that are not that He might bring to nought things that are that no flesh should glory in his sight. I Corinthians 1:27-29

Preface

Is this a book of biography, or is it romance? The author himself scarcely knows. If an honest attempt to give the facts makes biography, then he hopes it may deserve that title. If an effort to interpret some of those facts and give them life makes romance, then must his work be called romantic. In either case he hopes that the picture in each case is true; and that the whole is a proof of a deeper truth which it is needful for us all to remember. It is, that "God is wonderful in His saints"; that He "chooses whom He will Himself"; that in His house "there are many mansions"; and that there is no condition of life to which His grace does not reach, none so low but He can make it worthy of Himself.

We have called this book "Saints for Sinners," and in doing so we would take the word "Sinners" in a broad sense. For beside the actual consciousness of sin, and the sense of weakness that comes of it, there is also a kindred consciousness of failure, and ineffectualness, and other hard things in the spiritual life which makes us realize our utter nothingness, and compels us sometimes to wonder whether we are not ourselves their cause. When these hard things oppress us, and tempt us to despair or resent, it is well to bear in mind that they were the lot of all the saints, that "virtue is made perfect in infirmity," and that the life of the Cross is an ideal above every other, however human nature may stumble or be scandalized. For this reason, in these chapters, the human element has been more considered than the sanctity that has been built upon it; the latter rises in proportion to the depth of the foundation.

For permission to include in this book three studies, with some additions, which have already appeared in the "Month," the author is deeply grateful to its Editor.

St. Augustine Of Hippo354-430

Men approach St. Augustine with mixed feelings. So high does he tower above those of his generation, perhaps above those of every generation, that they look up to him with a certain awe, almost with fear. The very sight of his works, more, probably, than those of any other writer of the past, frightens us and puts us off; someone has seriously said that merely to read what Augustine has written would take an ordinary man a life-time. Nevertheless, to one who will have courage and come near, it is strange how human, and even how little in his greatness, Augustine is found to be. "I liked to play": "delectabat ludere," he said of himself in his childhood; and there is something of that same delight to be found in him to the very end of his days.

Augustine was born in Thagaste, a Roman town in Numidia, North Africa. It was a free town, and also a market-town, set at a place where many Roman roads converged; to it the caravans from east and west brought their merchandise, in it the luxury of Rome was repeated, with the added freedom of Africa. He was the eldest son of one Patricius, a well-to-do citizen of the place, a pagan but not a fanatic, whose ideal of life was to get the most out of it he could, without being too particular as to the means. Patricius, at the age of forty, had married Monica, a girl of seventeen, a Christian on both her father's and her mother's side. This marriage alone would seem to imply a certain laxity of faith in the family; the fact that Monica owed most of her religious and moral training to an old nurse confirms it.

It cannot be said that the marriage was a happy one. Perhaps it was not intended to be; it was a marriage of convenience and no more. For the pagan Patricius it meant life with a woman who, the older she became, and the more difficult her situation, clung the more to her own religion, and would have nothing to do with his free and easy ways, to call them by no worse name. For Monica it meant a life of constant self-suppression; of abuse even to blows, for Patricius had fits of violent temper; of slander on the part of those who were only too anxious to pander to Patricius, or were jealous of the influence her meek disposition had upon him. Three children were born to them, Augustine the first, but none of them were baptized. In those days a middle course was found. As children were born they were inscribed as catechumens; the baptism might come later, perhaps whenever there was danger of death.

Augustine grew up among pagan children, apparently in a pagan school, and his morals from the first were no better than theirs. He could steal, he could cheat, he could lie with the best of them; to do these things cleverly and successfully was a mark of talent rather than of vice. He went to school, and he hated it, both its restraint, and the things he had to learn. He was thrashed repeatedly, and when he came home received little commiseration, even from his own mother. His boyhood, from his own description, was an unhappy time; it tended to make him all the more bitter and reckless. But he was a precociously clever child, and in spite of his thrashings, which only made him more obstinate, and his own idleness, he learned more than his companions. Both his father and his mother became ambitious for him; they decided to give him a better education than could be given him in Thagaste. He was sent to Madaura, a prosperous city thirty miles away.

But thirty miles, in those days, and for a boy such as Augustine, was a great, separating distance. Here at last he was his own master; the longing he had always had to do just what he liked, without let or hindrance from anyone, was allowed free scope. He studied the pagan classics, for he loved to read and read; he studied not only their literature, but also their ideals and their life. These were exemplified all around him, and he could take part in them as much as he pleased; the pursuit of pleasure at all costs, the wild orgies of the carnivals of Bacchus, the worship of the decadent Roman ideal, smart, sensual, excusing, boldly daring, laughing with approval at every excess of sinful love. Such was the atmosphere the clever, imaginative, craving, reckless Augustine was made to breathe in the city of Apuleius at the age of fifteen; and to face it he had nothing but the flattering encouragement of a pagan father, the timid fear of a Christian mother whose religion he had already learned to despise. He soon became simply a pagan, a non-moral pagan at the most critical time of his life.

The consequences were inevitable. Augustine came home from Madaura addicted to the lowest vices. What was worse, he seemed to have no conscience left; worse still, he had a father who looked upon the same excess as a proof of manhood, the sowing of wild oats now which gave promise of great things later. Only one chain held him, the love he had for his mother. He laughed at her pious ways, he deliberately defied and hurt her; but underneath, though he tried not to own it to himself, his respect and admiration and affection for her had steadily increased. It was the same on her side, which made the bond all the stronger. Monica's life with her husband had been unhappy and loveless; and the love she longed to give was poured out on her favorite yet reckless son. The more she loved him, the more she was appalled at the life he was already living, and at the future to which it must inevitably lead. She blamed herself for having been partially the cause of his downfall. She had encouraged the plan of his going to Madaura; she had given him little to protect him while he was there; she would do all she could to win him back, though it was to be the struggle of a life-time. This made her strive all the more for her own perfection; if she was to influence him at all she must herself be true. Since she could say little to him, she would pray for him; she watched him, but it could only be from a distance. And Augustine, though he made nothing of it at the time, though he often took delight in hurting her by his boast of wickedness, knew nevertheless that she prayed, and watched, and loved; and he returned that love, and it grew.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Saints for Sinners»

Look at similar books to Saints for Sinners. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Saints for Sinners and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Rev. Fr. Alban Butler - Lives of the Saints (with Supplemental Reading: A Brief Life of Christ) [Illustrated]](/uploads/posts/book/269975/thumbs/rev-fr-alban-butler-lives-of-the-saints-with.jpg)