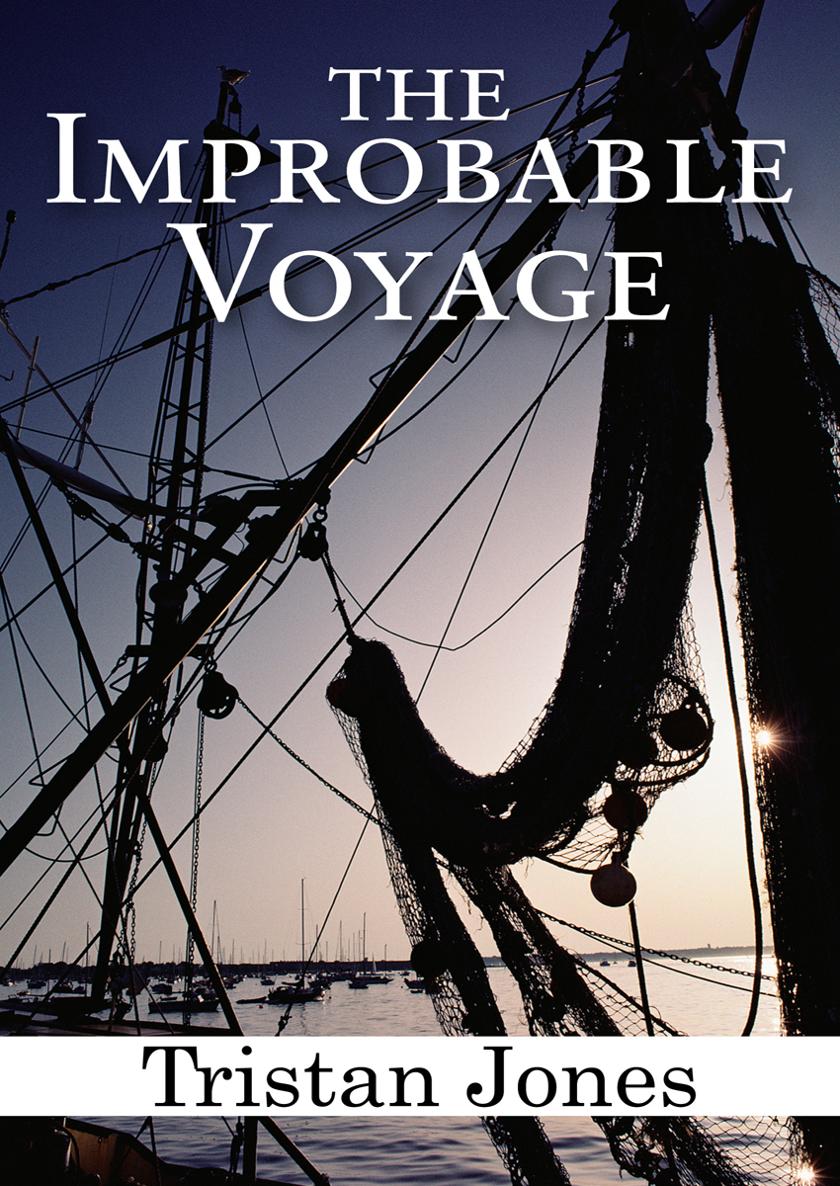

Foreword

This is a true yarn written by a sailor for, among others, fellow sailors. Some of these fellow sailors may, I hope, make this voyage with greater ease in the future. I have included in the story some information on things that matter to voyagers: depths of water, berthing, supplies and freshwater sources, and suchlike. I know that these matters will interest my fellow voyagers. I trust that they will not tire the general reader.

This is the story of one boats extraordinary voyage, not a book about land travel through countries or cities. Here you will find little about art galleries or museums, or even history. Here you will find mainly the view from an oceangoing vessels deck as she makes one of the most onerous and wonderful small-craft voyages of recent times.

I can only hope that the references to the needs of voyagers and to the knowledge they may need will serve to add to the novelty and strangeness of the whole real-life venture.

My voyage was made against the advice of most of the worlds foremost authorities on exploration, river navigation and ocean voyaging. Only two persons among them thought it might be possible. For the rest, they washed their hands of me and wished me well (and probably good riddance). To those two people I dedicate this book.

On board Outward Leg

Meghisti,

Nisos Kastellorizo,

Greece

SeptemberOctober 1985

PART ONE

Into

River Danube, called Donau in Germany, Duna in Austria, Dunaj in Czechoslovakia, Dunav in Yugoslavia, Dunarea in Rumania and Dunay in U.S.S.R., the largest river in Europe except the Volga... debouches through a delta into the Black Sea after a course of about 1,750 miles.

Between Neustadt and Regensburg the river forces its way through a narrow, cliffy defile nearly one mile in length. At the eastern end of the defile is Kelheim... and as the Ludwig canal connects River Altmhl with River Main in Bamberg, it is possible to traverse the European continent, by water, from the North Sea to the Black Sea.

The Black Sea Pilot, 1969

British Hydrographic Department,

Ministry of Defence.

Scheisse!

Unknown German official, Ludwig

Kanal 1944.

Bloody hell!

The author when he saw why the

German official had cursed in 1944.

5 December 1984

1. On Pioneering

What Im writing now is an amalgam of my thoughts as they were in St. Katharines Dock at the prospect ahead, and my conclusions now in Kastellorizo after the fact, a year and three thousand miles later. For the average small-craft voyager three things are certain: if he waits until his boat is one hundred percent ready, or if he waits until he has enough money for the whole voyage, or if he listens to most sensible people, hell never get away from the dock.

Its different if the voyage is sponsored, of course; then some sensible people, with money invested by the barrel load, and anxious for a return on the investment, will push the poor sod out to sea as quickly as possible, whether his boats ready or not. But they wont do it for the impossible voyages. They wont touch those with a barge pole. It doesnt suit their landsmens views.

Thats a good thing for the impossible voyager. It leaves him short of money; most of the time chronically short, and his boat is rarely wholly shipshape, but if hes worth his own salt he does get away from the dock. He might come a cropper in short order, but at least he makes a start, even though he might have no idea of how the voyage will carry on in the later stages. If the voyage doesnt start, then it was just a dream anyway and for him it is better for it to die than for the sensible people to lay hands on it. Money, although it helps, doesnt make real dreams come true; only faith, hope and compassion can do that, and patience; but the voyager cant be too patient or time will erode his dream.

My dream in 1984, and indeed for many years before that, was to pass an oceangoing craft right through Europe by way of the Rhine and Danube. I made ready in St. Katharines Dock, London, in October 1984.

Most people who have never made a long river voyage imagine that it must be far easier and safer than making voyages across oceans. The reverse is generally true. On an ocean passage, for ninety percent of the time, on average, a boat, if she is properly navigated, is clear of hazards. On a river passage, under way, a boat is rarely, if ever, clear of hazards. The chances of an accident to the vessel and to the people in her are much, much more on a long river passage than out at sea. That might not seem so to the average landsman, but that is because inland on a river he is surrounded by familiar things; land and trees and people, towns and villages, and does not understand the hazards of shoals and fast currents. I have known some of the toughest voyagers dead and alive, and not one of them would not blanch at first sight of the upper river Danube in full spate.

I have voyaged all the oceans in the world. Only two months before I headed for the Rhine I had made a transatlantic passage in Outward Leg. I can truthfully say that the voyage across Europe was far more hazardous than any ocean leg, both to me and the boat. We crossed the Atlantic, both of us, with not a scratch; as you will see, by the time we emerged from the Danube into the Black Sea we were both battered and bruised, almost beyond bearing.

This only goes to prove what Ive been saying for a long time about ocean passages; its the unexpected, the unknown element, the dark side of ourselves, that frightens us. Its being away from the rest of humanity, in the dark spaces, alone, thats the real fear, not the prospect of death or disablement. These risks are far greater on a long river passage, yet we can accept them, or even dismiss them from our minds because we foolishly imagine that death might be easier in familiar surroundings or in company. Thats an illusion, because everyone dies alone, wherever he is. Considering some of the company on the rivers we voyaged, and especially in the lower reaches of the Danube, I think it would be infinitely preferable to die alone in the clean open reaches of the ocean.

The very fact that my boat is twenty-six feet wide was enough to put off most of the sensible people. The depth of her they didnt even think of, although to me that was far more important. If she had been one inch deeper the voyage could not have been madebut I might have cut off the offending inch. Her height, even with the mast down, was crucial, too. As it was we lowered it by six inches and even then, in some places, she cleared bridges with only an inch to spare.