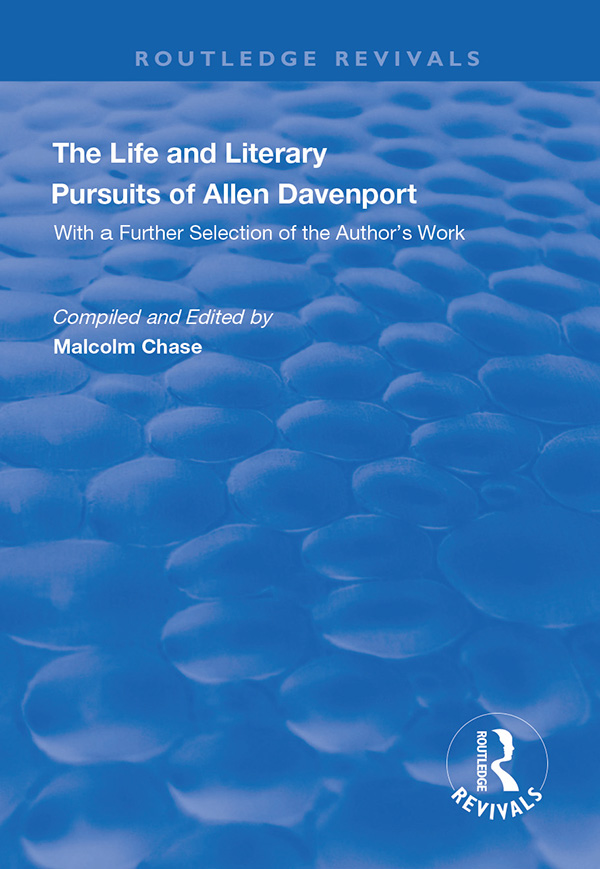

First published 1994 by Scolar Press and Ashgate Publishing

Reissued 2018 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY I 0017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright The Editorial Introduction and Afterword, copyright Malcolm Chase, 1994

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 94005838

Typeset by Raven Typesetters, Ellesmere Port, S. Wirral

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-33741-1 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-33742-8 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-429-44238-4 (ebk)

Allen Davenport (1775-1846) was a moderately important figure in British radical politics during the first half of the nineteenth century. Born in Gloucestershire, one of the ten children of an impoverished handloom weaver, he received no formal education. His political career was spent in London, but had a national dimension due to his prominence as a radical land reformer. Davenport was also among those who formed the backbone of the revolutionary underground movement in Regency London. He was an early, though critical, follower of Robert Owen; one of the first male supporters of feminist causes and of birth control; and he was an important link between the Chartist movement and the heritage of the French Revolution era. Finally he was a prolific author, political journalist and poet. Underpinning all these activities was an abiding commitment to working-class self education, but also a life-long experience of poverty.

Davenport published his autobiography in 1845, and it initially attracted much interest in Chartist circles. However, no copy appears to have survived in any British or European collection. Since it was long presumed lost, historians had to make do instead with tantalising fragments from the contemporary radical press.

This volume incorporates both works in their entirety. Some shorter works appended to the originals are also reproduced. Davenport apparently intended them to constitute definitive specimens of the authors style in the department of polite literature. A key problem, however, is that these specimens are exactly as he described them: polite. His most interesting and important work was considerably less polished than the prose and verse he chose to reprint at the end of his life. This contrast reflects the essential tension of his autobiography, and of the life of its author. Davenport was a prolific radical writer; he brought to this aspect of his work the same passion and at times revolutionary vehemence that underpinned his political activity generally. However, this was an aspect of his life that Davenport as an autobiographer was strongly inclined not to emphasise. The works he chose for republication were assessed against two criteria: his literary pretensions and the respectable radical culture of his last years. The result was far from representative of Davenports output, and to reprint it alone would do a disservice both to the authors reputation, and to any modern reader interested in either popular politics or non-canonical authors of the nineteenth century. A further and more-representative selection of Davenports political journalism and poetry has therefore been included in this edition, containing several important but not-easily accessible items from British collections. Collectively, the works of Allen Davenport reprinted here provide a unique window on to working-class radicalism in the crowded years from Peterloo to Chartism.

Sketching Davenports life in his own autobiography, the veteran cooperator and freethinker George Holyoake wrote:

He will have no other biographer The poet was thin, and pale, and poor. He lived about the East End, was known at every workmans political meeting, and any surplus over his personal needs arising from his daily labour, was spent in publications giving information to men of his order, whom he sought to serve.

Allen Davenport has another biographer at last: my thanks are due to a number of people who have made this possible, principally David Goodway, and the Library of Vanderbilt University for providing copies of the originals of Davenports Life and Literary Pursuits and The English Institution in its care. The high priority accorded by the Library and University to the care of the Mtivier Collection has placed all historians of nineteenth-century radicalism in their debt. John Harrison first encouraged my interest in Davenport, and Joyce Bellamy and John Saville, in the course of editing my entry on him in the Dictionary of Labour Biography, did much to help sharpen my perception of his contribution to nineteenth-century popular politics and education. My special thanks are due, as always, to Shirley Chase.

Notes

Throughout the texts that follow, Davenports original (and often overlavish) punctuation has been retained. Spelling errors in the originals have likewise been left uncorrected.

Davenports Life faded from view following the appearance of an extract in the National Co-operative Leader (8 and 22 March 1861). That, and a contemporary review in the Northern Star, prompted labour historians in the 1960s to search for a surviving copy: see Harrison, 1961, p. 14.

The background to the discovery of the collection is described in Goodway, 1984b, pp. 57-60. The collection has since been re-assembled from the Librarys open shelves and catalogued: see Hambrick, 1986.

Life, p. 77 - see below p. 30.

G. J. Holyoake, Sixty Years of an Agitators Life (3rd edition, 1893), volume 2, page 263.

AUTHOR OF THE MUSES WREATH, LIFE OF SPENSE,

Written by Himself.

How chequered are the paths of human life,

How small the joy, how great the care and strife!

How varied are the prospects that arise,

How many changes pass before our eyes!

And when the flowry landscape we pursue,

Dark clouds descend, and mock our anxious view.

Ought not these lessons of our social plan,

Teach justice and humanity to man?

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR, BY G. HANCOCK,

ALDERMANBURY.

1845.