Title: The Life of the Rt. Hon. Sir Charles W. Dilke V1

Author: Stephen Gwynn

Release Date: January, 2005 [EBook #7382] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on April 22, 2003]

Edition: 10

Language: English

THE LIFE OF THE RT. HON. SIR CHARLES W. DILKE, BART., M.P.

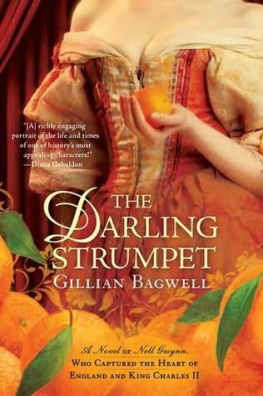

[Illustration: RT. HON. SIR CHARLES W. DILKE, BART., M.P., IN THE

YEAR 1873.

From the painting by G. F. Watts in the National Portrait Gallery.

Frontispiece, Vol. I.]

THE LIFE OF THE RT. HON. SIR CHARLES W. DILKE BART., M.P.

BEGUN BY STEPHEN GWYNN, M.P.

COMPLETED AND EDITED BY GERTRUDE M. TUCKWELL.

IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I.

PREFACE

The following Life of Sir Charles W. Dilke consists mainly of his own

Memoirs and of correspondence left by him or furnished by his friends.

The Memoirs were compiled by Sir Charles Dilke from his private diaries and letters between the years 1888 and his return to Parliament in 1892. The private diaries consisted of entries made daily at the dates dealt with. Of the Memoirs he says: "These notes are bald, but I thought it best not to try, as the phrase goes, 'to write them up.'" In some cases the Memoirs have been condensed into narrative, for Sir Charles says of the periods his "notes" cover: "These chapters contain everything that can be used, and more than is needed, and changes should be by way of 'boiling down.'" The Memoirs were unfinished. He writes in May, 1893: "From this time forward I shall not name my speeches and ordinary action in the House, as I had now regained the position which I held up to 1878, though not my position of 1878-1880, nor that of 1884-85;" and as from this point onwards there are few entries, chapters treating of his varied activities have been contributed by those competent to deal with them.

Sir Charles Dilke's will, after giving full discretionary powers to his literary executrix, contains these words: "I would suggest that, as regards those parts relating to Ireland, Egypt, and South Africa, the same shall be made use of (if at all) without editing, as they have been agreed to by a Cabinet colleague chiefly concerned." A further note shows that, so far as Ireland was concerned, the years 1884-85 cover the dates to which Sir Charles Dilke alludes. The part of the Memoirs dealing with these subjects has therefore been printed in extenso, except in the case of some detailed portions of a discussion on Egyptian finance.

The closing words of this part of Sir Charles Dilke's will point out to his executrix that "it would be inconsistent with my lifelong views that she should seek assistance in editing from anyone closely connected with either the Liberal or Conservative party, so as to import into the publications any of the conventional attitude of the old parties. The same objection will not apply to members of the other parties." In consequence of this direction, Mr. Stephen Gwynn, M.P., whose name was among those suggested by Sir Charles Dilke, was asked to undertake the work of arranging the Memoirs, and supplementing them where necessary. This work was already far advanced when Mr. Gwynn joined the British forces on the outbreak of the War. His able and sympathetic assistance was thus withdrawn from the work entailed in the final editing of this booka work which has occupied the Editor until going to press.

A deep debt of gratitude is due to Mr. Spenser Wilkinson, who has contributed the chapters on "The British Army" and "Imperial Defence." Sir George Askwith was good enough, amidst almost overwhelming pressure of public duties, to read and revise the chapter entitled "The Turning- Point." Sir George Barnes and Sir John Mellor have also freely given expert advice and criticism. Mrs. H. J. Tennant, Miss Constance Smith, Mr. E. S. Grew, Mr. H. K. Hudson and Mr. John Randall have given much valuable assistance. The work of reading proofs and verifying references was made easy by their help.

While thanking all those who have placed letters at her disposal, the

Editor would specially acknowledge the kindness with which Mr. Austen

Chamberlain has met applications for leave to publish much correspondence.

Mr. John Murray's great experience has made his constant counsel of the utmost value; and from the beginning to the close of the Editor's task the literary judgment of the Rev. W. Tuck well has been placed unsparingly at her service. Sir H. H. Lee and Mr. Bodley, who were Sir Charles Dilke's official secretaries when he was a Minister, have given her useful information as to political events and dates.

To the many other friends, too numerous to name, who have contributed "recollections" and aid, grateful acknowledgments must be made.

Finally, the Editor expresses her warmest thanks to Lord Fitzmaurice, who has laid under contribution, for the benefit of Sir Charles Dilke's Life, his great knowledge of contemporary history and of foreign affairs, without which invaluable aid the work of editing could not have been completed.

INTRODUCTION

The papers from which the following Memoir is written were left to my exclusive care because for twenty-five years I was intimately associated with Sir Charles Dilke's home and work and life. Before the year 1885 I had met him only once or twice, but I recall how his kindness and consideration dissipated a young girl's awe of the great political figure.

From the year 1885, when my aunt, Mrs. Mark Pattison, married Sir Charles, I was constantly with them, acting from 1893 as secretary in their trade- union work. Death came to her in 1904, and till January, 1911, he fought alone.

In the earlier days there was much young life about the house. Mrs. H. J. Tennant, that most loyal of friends, stands out as one who, hardly less than I, used to look on 76, Sloane Street, as a home. There is no need to bear witness to the happiness of that home. The Book of the Spiritual Life, in which are collected my aunt's last essays, contains also the Memoir of her written by her husband, and the spirit which breathes through those pages bears perfect testimony to an abiding love.

The atmosphere of the house was one of work, and the impression left upon the mind was that no life was truly lived unless it was largely dedicated to public service. To the labours of his wife, a "Benedictine, working always and everywhere," Sir Charles bears testimony. But what of his own labours? "Nothing will ever come before my work," were his initial words to me in the days when I first became their secretary. Through the years realization of this fact became complete, so that, towards the last, remonstrances at his ceaseless labour were made with hopeless hearts; we knew he would not purchase length of life by the abatement of one jot of his energy. He did not expect long life, and death was ever without terror for him. For years he anticipated a heart seizure, so that in the complete ordering of his days he lived each one as if it were his last.

The house was a fine school, for in it no waste of force was permitted. He had drilled himself to the suppression of emotion, and he would not tolerate it in those who worked with him except as an inspiration to action. "Keep your tears for your speeches, so that you make others act; leave off crying and think what you can do," was the characteristic rebuke bestowed upon one of us who had reported a case of acute industrial suffering. He never indulged in rhetoric or talked of first principles, and one divined from chance words of encouragement the deep feeling and passion for justice which formed the inspiration of his work.