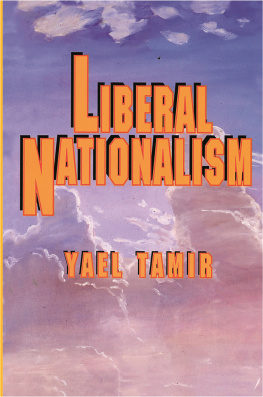

FOREWORD

This is a book I had to write. George Weidenfeld, my British publisher and friend, believed it should be published, and read as well. I thank him affectionately for his unfailing confidence.

Dov Sion, my husband, objects to and abhors any self-induced exposure. With gentleness and understanding, he deviated from this principle and gave me his full support during the long and often painful writing of this book. David Rieff, senior editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux, was my first objective reader. I am indebted to him not only for editing the manuscript for publication but for easing my anxieties and enabling me to work with the right perspective on the final version.

My friends Shimshon Arad, Kay Cohen, Bess Simon, Betty Epstein, Marianne Griessman, and Ira Bermak were kind enough to read the book in manuscript form. For their comments, encouragement, and support, I am profoundly grateful.

I must mention with thanks Pamela Levy, who managed the impossible and turned the undecipherable handwritten manuscript, with attention and care, into a typed readable one.

My mothers contribution to this book was invaluable. She made available to me her amazing memory and the hundreds of letters my father wrote her. She let me touch exposed sensitive nerve ends and bravely removed protective fences in order to help me learn and understand.

My brothers role in my life and my fathers is reduced to a minimum in this book. That does not reflect reality but their wish, which I wholeheartedly respect. They may want to tell their own stories one day, and it should be their prerogative when and how to do it.

My father wrote me when I was working on my first book: As you are writing a book, you should put all your efforts into making it a good one, and when I say good, I mean honest. I see no harm in full exposure of inner statements, providing you dont compromise on honesty. It comforts me to think that, were he alive and read this book, he would have been satisfied that no such compromise was made.

Y.D.

Memories are not history. They are fragments of things and feelings that were, tinted and sifted through varying prisms of present time and disposition. This book, then, is not the story of Moshe Dayan, or my own life story, but an attempt to depict a relationship of four decades between a father and a daughter, from birth to a mature emotional and spiritual connectionone that to some extent has survived death and still continues to inspire and have meaning.

I have not aimed for objectivity of any kind. That would be absurd and pretentious, since I was and am a participant rather than an observer. What truth I can offer is neither historic nor scientific; my own subjective, intense, one-sided, emotionally loaded truth. If my portrait of my father clashes with the memories or observations of others, that does not mean I doubt their truth or mean to impugn their Moshe Dayan. My father had a number of significant relationships in his life. In this book, I will consider them subjectively from the vantage point of my own involvement. My mother, my brothers, my fathers friends, and his second wife may see that their perceptions of some of the episodes in my fathers life or of elements of his character are different from mine, but then, their memories are not history, either.

ONE : A LONG FRIDAY

I am compelled to begin with the end, with the image of my father as a dead man, devoid of heartbeat and blood pressure, feeble and small in the intensive-care unit. A body still connected to tubes and electrodes, its maimed face turning yellow; gray fingers; a deep scar for an eye; a meaningless green line on an EKG screen.

I have seen many dead faces. Tranquil or accepting, amazed or tortured, childish or wrinkled. My fathers conveyed angry frustration, as if he didnt mean it to happen quite then, and for the first time ever was caught unaware, deprived of the last word. Those things unsaid and unaccomplished hovered there, almost palpable. This furious aura has haunted me ever since.

Early on Friday, October 16, the phone woke me long before the alarm clock, set for six-thirty, went off. This was not in itself unusual. My fathers wife, Rahel, was on the other end of the line, assuring me there was no cause for alarm. He had been in the hospital for a few hours, having had pains the night before. He had refused to be carried to the ambulance and insisted on walking, had been conscious and stable when admitted, and was refusing to see any visitors. There were no tears in Rahels voice, nor was there a false effort at cheerfulness. Rahel simply didnt know more than she communicated, and I hung up with an enormous sense of anxiety.

The morning news on the radio contained the brief statement that Moshe Dayan had been hospitalized due to a heart problem and that, according to the doctors, his condition was stable. I packed my children off to school and drove to Tel Hashomer Hospital in the heavy morning traffic, turning the radio on loud to block thought. It was not the first time I had driven in haste to Tel Hashomer to be at my fathers bedside. There had been the time when, while he was excavating for antiquities, a hillside had caved in on him and almost crushed him to death; then there was the year he was operated on for cancer of the colon; and there had been other, more minor occasions. My father had suffered from heart disease for a long time. He was an undisciplined patient. But he had taught me to think logically, and I strove not to give way to premonitions or emotionalism as I drove to the hospital. I shifted gears automatically, stopped when the traffic lights turned red, drove by the maternity ward where both my children had been born; I parked and walked to the intensive-care unit of the cardiology department. The attending doctor greeted me unsmiling and refused to go further than to describe the situation as stable. Rahel was there, looking tired and pale but not desperate or hysterical. He was in a small room, lying on a narrow bed. Although sedated, my father was awake and irritable, and he didnt want to see me. She said she was sorry, since she knew how I felt, but there was no persuading him. She told me my father had ordered everybody out, and promised to call me later and tell me when to come.

Mumbling something about calling my brothers, I turned to listen as the young cardiologist explained to me in detail my fathers heart-muscle malfunction. I remember looking at the small screen which was transmitting electronic signals from his heart. The lines went up and downpretty green lines. Although my father wouldnt see me, I stood at the edge of his room, watching him through the half-drawn curtain. His good eye was weakening, tragically so, and he couldnt have seen me even if hed been able to keep it open, which he didnt. His face had the intensity of an angry fighter unable to grasp the dreadful thing that was happening to him. It was then I realized I had arrived too late. My belief in his love for me wasnt shattered, for I knew he couldnt face me. Had I walked in, he would have realized how near he was to his death.