This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHING

Text originally published in 1827 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2011, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

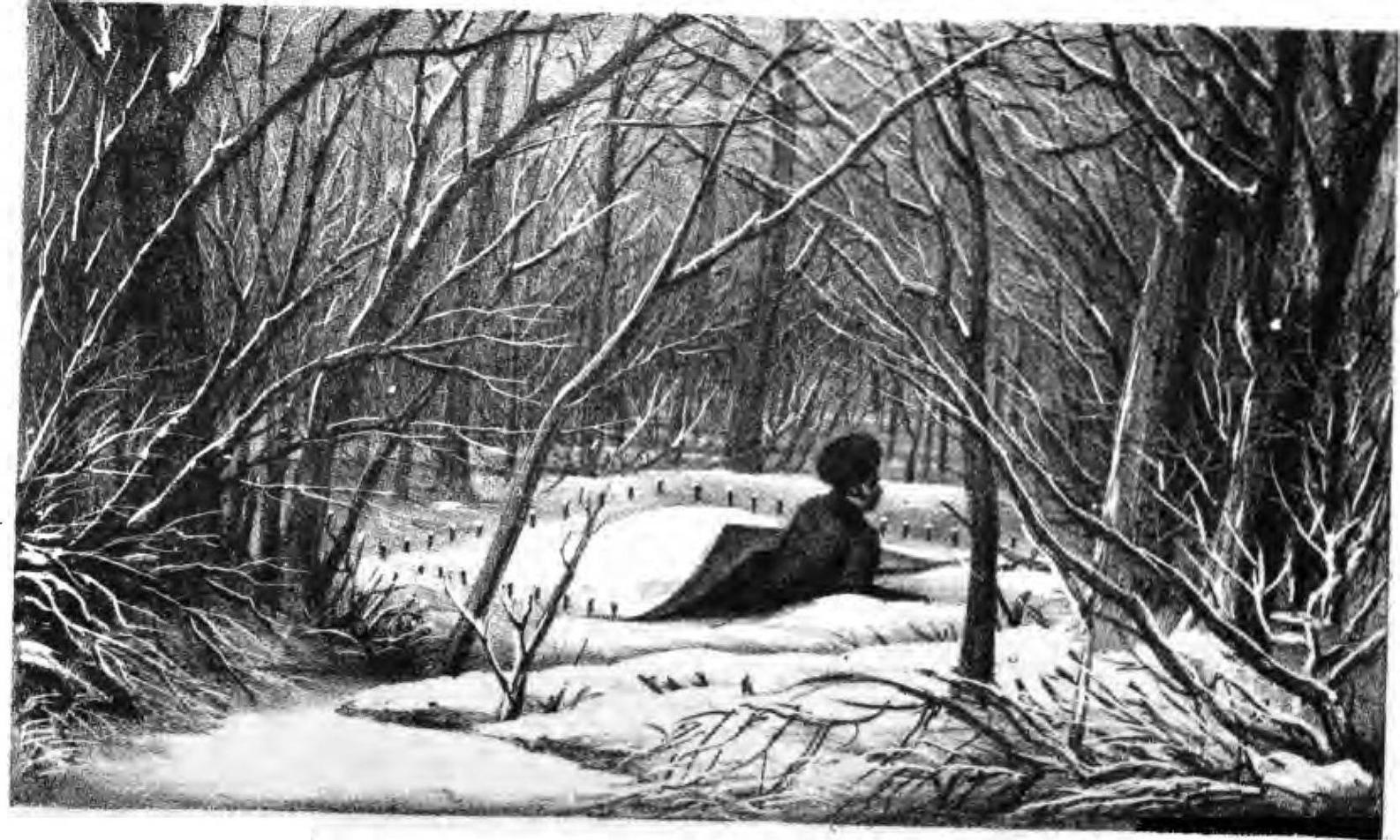

The Situation of the Author in the Wood coming out from under the Horse Cloth.

TO

REAR ADMIRAL

SIR EDWARD W. C. R. OWEN, K.C.B. M.P.

SURVEYOR GENERAL OF THE8 ORDNANCE,

&c. &c. &c.

THIS LITTLE VOLUME,

CONTAINING

A PLAIN AND UNPRETENDING

NARRATIVE OF FACTS,

AS A TRIBUTE OF HIGH ESTEEM,

AND SINCERE REGARD,

IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED,

BY

HIS OBLIGED FRIEND AND SERVANT.

THE AUTHOR.

PREFACE.

THE following "Narrative" was written in the West Indies, in 1810, at the previous suggestion, and for the sole amusement, of my own family; since which, it has undergone occasional revision, both with a view of leaving to my children a memento of their father's juvenile adventures, and also of committing it to press, should more competent judges deem such a course not to savour of presumption.

The reader, who may run through this little volume, will not fail to observe, that it could not have been published at the time it was written, without risk of injury to those to whom I was indebted for protection; and when this cause ceased to operate, in consequence of the number of years which had elapsed, I still delayed the publication, from the fear it might not be found worthy the attention of the public. At length, however, trusting in the indulgence so generally shown to one who is not an author by profession, and more especially to the liberality of my brother officers, I venture, late as it is, (but not without much diffidence) to publish this plain statement "of facts," requesting the candid reader to bear in mind, that I make no pretensions to literary merit, my sole object being to convey the simple truth, in its simplest form.

NARRATIVE.

AT the termination of the war, in the spring of 1802, I was paid off as a master's mate of the Royal Sovereign, bearing the flag of Vice Admiral Sir Henry Harvey, K.B. In June following, I joined the Phbe frigate; in September, captain the Hon. T. B. Capel was appointed; we were sent to the Mediterranean, and there continued until the renewal of the war in 1803. In July, the Phbe was ordered off Toulon, to watch the enemy in that port: on our way thither, when off Civita Vecchia, two privateers were seen from the mast head, it being then ,a dead calm; the boats, ably manned and well armed, were dispatched in chace, under the orders of the first Lieutenant Perkins, and after five hours' rowing, about ten P.M. came up with one of them; but from an unfortunate medley of disastrous events, we were twice repulsed with the loss of eight men killed and wounded.

Having reached our station off Toulon, on the night of the 31st of July, two armed boats under the orders of Lieutenant Tickell, with one of which I was entrusted, were sent in shore for the purpose of capturing any vessel running along the coast, that he might judge worth the risk of attack; having gained an eligible situation, under the land, near Cape Cecie, we lay upon our oars until dawn of day, when two settes were discovered standing to the westward, with a light breeze, they were instantly boarded, and carried, without resistance; they proved to be from Genoa, bound to Marseilles, with fruit and sundry merchandize. On rejoining the Phbe, the sails of the prizes were found to be in such a tattered state, that Captain Capel judged it proper to detain them two days in order to have them repaired, when I was appointed prize master to one, and a midshipman, named Murray, to , the other, having with him an assistant brother officer, named Whitehurst. Our orders were to proceed the following day to Lord Nelson, then off the coast of Catalonia, and thence to Malta; unhappily for me it was otherwise ordained; for at break of day on the 4th of August, four frigates, viz. "La Corneille, (Commodore) Le Rhin, L'Uranie and La Thamise" were discovered about five miles astern; all sail was immediately crowded upon our little squadron, steering about S.S.W. with a moderate breeze from the W.N.W.; as the day broke, the Redbridge schooner hove in sight on the larboard bow upon the opposite tack, having a transport under her convoy, and, passing within hail of the Phbe, soon after spoke me. The lieutenant recommended my tacking and following him; but as I saw that, by so doing I should, be running into the teeth of the enemy, and inevitably taken, in a quarter of au hour, I preferred executing my captain's orders, by keeping my station as long as I could: to this end we cut the long boat adrift, and began to lighten the vessel by throwing the cargo overboard, and setting every yard of canvase that could stand; but, notwithstanding all our efforts, the enemy was rapidly gaining both on myself and on the Phbe, and escape for either appeared impossible.

Seeing the Redbridge persevere in endeavouring to cross them, it occurred to me that Captain Capel might probably have directed the lieutenant to take the prizes under his convoy, and stand to the northward, in order to create a diversion, and thereby separate the pursuing enemy; this idea was strengthened by soon after observing the weathermost open her fire upon the schooner, which immediately struck, and, together with the other settee, hove too. The time lost in exchanging the prisoners, indicating no very zealous anxiety to resume the chase, also tended to confirm my suspicion; hence, doubting whether I had not erred in neglecting the advice (for it did not amount to an order) of the lieutenant of the Redbridge, I determined on bearing up, in the hope of getting to leeward, and enticing one of the frigates after me. At this time I was about three miles on the weather bow, and the Phbe about four, a head, of the French squadron. Scarcely were the sails trimmed, and the impossibility of escape obvious, than I determined on running the vessel athwart hawse of the headmost, in the hope of doing some mischief, and thereby facilitating the escape of the Phbe; but this design was frustrated by our own helmsman, who, being a Frenchman, {1} and alarmed at the enemy's threat to sink us, disobeyed my orders in the conning {2} of the vessel. Seeing her spring too, I ran aft, to the helm, but it was too late, our rigging just cleared the main chains of the frigate, which, to my utter astonishment, hove too, and sent a boat to take possession; thus, by a voluntary and unnecessary act, did the enemy execute that, which I had fondly hoped to effect, and which was almost the only act that could afford consolation in so painful a situation; for, notwithstanding I was myself a prisoner, I could but indulge in feelings of triumph at seeing the Phbe walk off in the face of a superior and much faster sailing foe. As the other frigates closed, they also hove too, thus allowing the Phbe to make one of the most miraculous escapes that occurred during the war. In the mean time the corvette captured the transport. About half an hour was occupied in removing the prisoners and dispatching the prizes to Toulon: during which period, the Phbe was manoeuvring in defiance, firing guns and making signals as if communicating with a friendly force. The chace was renewed, and an officer ordered to the mast head to look out, who reported that he saw several large sail to windward; the signal a fleet in sight, was immediately made to the commodore, and soon after the squadron bore up for Toulon; on approaching which, Admiral Gantheume, the commander in chief, by signal, ordered the chace to be resumed, evidently disapproving of the return; but the Phbe was then some distance to windward. Captain Capel, seeing the irresolution and want of energy in the French squadron, about four P.M. boldly bore down, fired at them, and hauled his wind again, as if desirous of enticing them off shore; between six and seven P.M. they gave up the chace, and again made sail for Toulon, followed by the Phbe. It is impossible to say with what discretionary power the commodore was invested, but it was nevertheless certain, from the decided advantage the French squadron had in sailing, that if they had continued the chace in either instance, the Phbe must have been taken, for there was no friendly ship of war within many leagues. During the night the squadron lay too off the mouth of the harbour, and when day dawned, again gave chace, which was continued all day, taking care not to reach too far off shore; in the evening they bore up and lay too as before. The 6th they again stood to sea, and returning, about sunset, anchored in Toulon roads. The pleasurable feelings of curiosity which every seaman experiences on entering a port which he has never before visited, were absorbed in the recollection that I was a prisoner, cut off from my country and friends, at the breaking out of a war, when I had served nearly seven years, and had buoyed myself up with the hope that I was on the very eve of promotion; these reflections, together with the conviction that I was so guarded as to preclude a probability of escape, tended to cast a temporary gloom over my spirits, and render me indifferent to the beauties of the surrounding scenery. The following day we were separately examined before officers sent on board for the purpose, and our refusal to answer questions, put to us, respecting the strength and situation of Lord Nelson, was construed into contempt, and so excited the rage of the captain of the Rhin, that he told us we were pirates; this novel information did not in the least disconcert us, for we suspected the ignorance of the man, and afterwards learnt he had been a barber; indeed, the whole tenor of his conduct evinced the dreadful convulsion which society in France must have undergone during the revolution, for such an ignorant, low-bred fellow to have risen to the command of a frigate. When, however, it was explained to him that midshipmen in the British navy never had commissions, he resumed his composure, and, on my producing Captain Capel's written order, I was dismissed. Whitehurst and Murray underwent similar examinations, but with no better success. During the twenty-one days we were on board the Rhin, under quarantine, the Phbe frequently hove in sight, and, as we were informed, made repeated proposals for an exchange of prisoners, but unfortunately, they were too well satisfied with such living proofs of their prowess in naval arms, to accede to them. We were occasionally permitted to take exercise in the quarantine ground, until the morning of the 26th of August, when Murray, Whitehurst, and myself, the master of the Transport and ninety men, were landed about two miles to the westward of the town; thus separating us from the officers of the schooner, consisting of Lieutenant M'Kenzie of the Maidstone, passenger, and six midshipmen, (Lieutenant Lempriere, the commander of the schooner, having been drowned in the roads, by the upsetting of a boat). Our separation from these officers, was caused by our conduct at the mock court of inquiry; we were told that we did not deserve to be treated like our comrades, and therefore were sent with the men: On landing, we were received by a captain's guard of infantry, who very uncourteously pushed us indiscriminately into ranks, and, forming themselves in file on each side, waited only the order to march, which was soon announced by a brace of dismal drums at the head of the escort, previous notice being given, through the medium of the interpreter, that the first who dared to wander from the ranks, would be shot. It was really ludicrous to witness the parade of triumph evinced by our commanding officer, and the readiness with which his every gesture was imitated by some of his obsequious subordinates, who liberally dealt out blows with the fiat of swords upon the shoulders of any one, who, even from awkwardness, might incline out of the direct line of march. In this way we trudged along, with each a loaf of ammunition bread slung over the shoulder, and only four dollars (which Whitehurst happened to possess) amongst us; occasionally halting to rest, until about four P.M. when we were drummed in form through a village, and then retrograded, for the purpose of being drawn up in front of a large swinery, to witness the expulsion of pigs, sheep, and goats, to make room for us. In the course of an hour, the lieutenant gave us leave to dine in the village, attended by a sergeant, by which he incurred the displeasure of his brutal captain; we soon after returned to the place of confinement, where we remained smothered in dust and dirt, until the morning, when we were again mustered into ranks, and after receiving a black loaf and seven-pence halfpenny each, as five days' pay, were drummed, as before, out of the village. Our march was through a rugged country, the scenery of which was very picturesque. The captain of the escort, generally keeping the interpreter by his side, occasionally (through him) entered into conversation with one or other of us; availing ourselves of a favourable opportunity, when apparently he was a little less morose than usual, we endeavoured to obtain permission to walk by ourselves, instead of being restricted to the ranks; but he was deaf to our request. We ceased to wonder that he should evince so little feeling for our situation, when he related story after story of the bloody deeds committed during the reign of terror, in which it seemed, by his own account, he had been a frequent and willing actor; he and the captain of the Rhin were, probably, fair specimens of the set of hardened miscreants which the revolution had produced, and served to show, that in those troublesome times, abandonment of principle and display of turpitude, no less than of talent, led the way to promotion and rank. The third night we arrived at Aix, and were confined in what appeared to have been an old convent, in the yard of which, being permitted to range, we seized the opportunity of washing our linen, and were much pleased to learn, that we were no longer to be escorted by that inhuman offspring of tumult, who had had charge of us from Toulon. He resigned us to the care of a venerable old gentleman, whose first act of kindness was to inquire, in what manner we had been treated by his predecessor, and who seemed indignantly surprised that no distinction had been made between the officers and the men. The knowledge of this unmerited and unjust severity excited his warmest sympathy, and called forth the exercise of those nobler feelings, which seemed to flow from a natural benevolence of heart, for his kindness and attentions were unbounded; whilst his affability and cheerfulness made us almost forget we were prisoners. "Voyons soyez gais," observed this good old gentleman, "the day may come when you may think yourselves happy in having been prisoners." Although I gave him full credit for his philosophy, and the benevolence which prompted the observation, and felt grateful for our change of treatment, yet the result proved him to be no prophet; for I have never had cause to rejoice at an event which kept me so many years back in the service; however, so it was, and I took advantage of my situation by endeavouring to learn something of the language, in occasional conversation with the interpreter; the next day's march brought us to a dirty village, where the church was our prison for the night. On the 1st of September, we reached Tarascon, and were locked up in the tower; before the old officer took leave, he ordered the jailor to place us in a comfortable room by ourselves, and treat us as officers, though not on parole, that being contrary to the order from Toulon; in the morning he took us for a walk through the town, and in the afternoon sent a boy with us up the river, where we enjoyed a refreshing bathe; after washing and drying our linen, we reluctantly returned to prison; this was the first time since our capture that we had been without a guard, and might have easily decamped, had we been so inclined; but certainly no opportunity, however tempting, could have induced us to violate the frank and friendly confidence reposed in us by our philosophical veteran; in the evening he again visited us, and with much feeling, recommended us to the particular indulgence of his successor, who, for the sake of distinction, was dubbed the