The Contemporary View of Bewick

Table of Contents

After 1790, when his A general history of quadrupeds appeared with its vivid animals and its humorous and mordant tailpiece vignettes, he was hailed in terms that have hardly been matched for adulation. Certainly no mere book illustrator ever received equal acclaim. He was pronounced a great artist, a great man, an outstanding moralist and reformer, and the master of a new pictorial method. This flood of eulogy rose increasingly during his lifetime and continued throughout the remainder of the 19th century. It came from literary men and women who saw him as the artist of the common man; from the pious who recognized him as a commentator on the vanities and hardships of life (but who sometimes deplored the frankness of his subjects); from bibliophiles who welcomed him as a revolutionary illustrator; and from fellow wood engravers for whom he was the indispensable trail blazer.

During the initial wave of Bewick appreciation, the usually sober Wordsworth wrote in the 1805 edition of Lyrical ballads:

O now that the genius of Bewick were mine,

And the skill which he learned on the banks of the Tyne!

Then the Muses might deal with me just as they chose,

For I'd take my last leave both of verse and of prose.

What feats would I work with my magical hand!

Book learning and books would be banished the land.

If art critics as a class were the most conservative in their estimates of his ability, it was one of the most eminent, John Ruskin, whose praise went to most extravagant lengths. Bewick, he asserted, as late as 1890, "I know no drawing so subtle as Bewick's since the fifteenth century, except Holbein's and Turner's." And as a typical example of popular appreciation, the following, from the June 1828 issue of Blackwood's Magazine, appearing a few months before Bewick's death, should suffice:

Have we forgotten, in our hurried and imperfect enumeration of wise worthies,have we forgotten "The Genius that dwells on the banks of the Tyne," the matchless, Inimitable Bewick? No. His books lie in our parlour, dining-room, drawing-room, study-table, and are never out of place or time. Happy old man! The delight of childhood, manhood, decaying age!A moral in every tail-piecea sermon in every vignette.

This acclaim came to Bewick not only because his subjects had a homely honesty, but also, although not generally taken into account, because of the brilliance and clarity with which they were printed. Compared with the wood engravings of his predecessors, his were more detailed and resonant in black and white, and accordingly seemed miraculous and unprecedented. He could engrave finer lines and achieve better impressions in the press because of improvements in technology which will be discussed later, but for a century the convincing qualities of this new technique in combination with his subject matter led admirers to believe that he was an artist of great stature.

William Wordsworth, Lyrical ballads, London, 1805, vol. 1. p. 199.

John Ruskin, Ariadne Florentina, London, 1890, pp. 98, 99.

Ibid., p. 246.

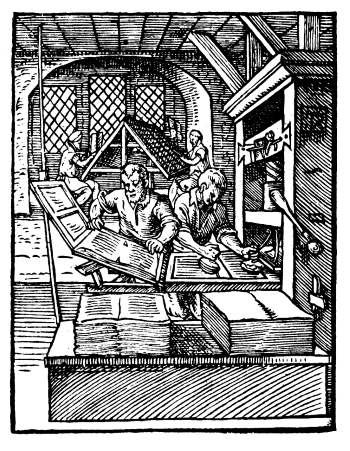

Later, more mature judgment has made it plain that his contributions as a craftsman outrank his worth as an artist. He was no Holbein, no Botticelliit is absurd to think of him in such termsbut he did develop a fresh method of handling wood engraving. Because of this he represents a turning point in the development of this medium which led to its rise as the great popular vehicle for illustration in the 19th century. In his hands wood engraving underwent a special transformation; it became a means for rendering textures and tonal values. Earlier work on wood could not do this; it could manage only a rudimentary suggestion of tones. The refinements that followed, noticeable in the highly finished products of the later 19th century, came as a direct and natural consequence of Bewick's contributions to the art.

Linton and a few others object to the general claim that Bewick was the reviver or founder of modern wood engraving, not only because the art was practiced earlier, if almost anonymously, and had never really died out, but also because his bold cuts had little in common with their technician's concern with infinite manipulation of surface tones, a feature of later work. But this misses the main pointthat Bewick had taken the first actual steps in the new direction.

William Linton, The masters of wood engraving, London, 1889, p. 133.

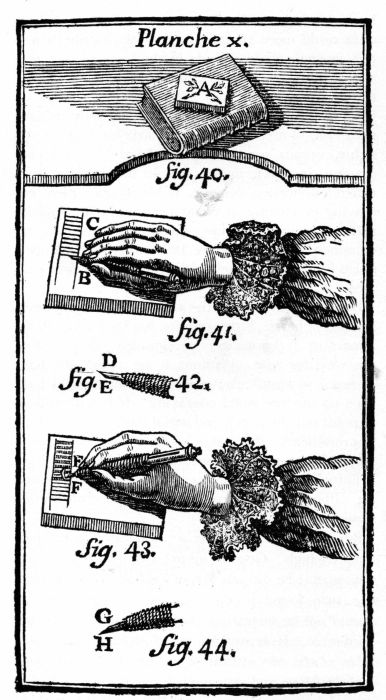

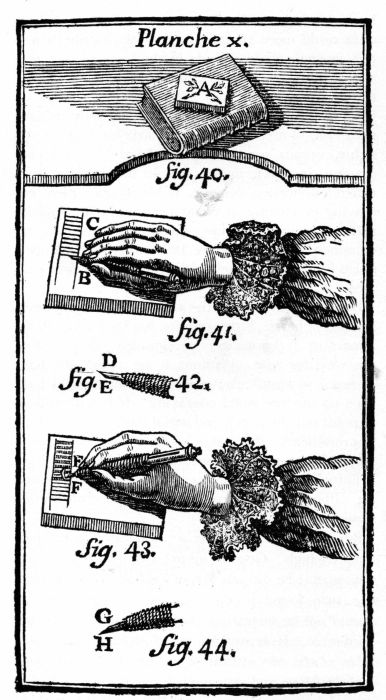

Figure 1. Woodcutting Procedure , showing method of cutting with the knife on the plank grain, from Jean Papillon's Trait de la gravure en bois, 1766.

Unquestionably he gave the medium a new purpose, even though it was not generally adopted until after 1830. Through his pupils, his unrelenting industry, and his enormous influence he fathered a pictorial activity that brought a vastly increased quantity of illustrations to the public. Periodical literature, spurred by accompanying pictures that could be cheaply made, quickly printed, and dramatically pointed, became a livelier force in education. Textbooks, trade journals, dictionaries, and other publications could more effectively teach or describe; scientific journals could include in the body of text neat and accurate pictures to enliven the pages and illustrate the equipment and procedures described. Articles on travel could now have convincingly realistic renditions of architectural landmarks and of foreign sights, customs, personages, and views. The wood engraving, in short, made possible the modern illustrated publication because, unlike copper plate engraving or etching, it could be quickly set up with printed matter. Its use, therefore, multiplied increasingly until just before 1900, when it was superseded for these purposes by the photomechanical halftone.

But while Bewick was the prime mover in this revolutionary change, little attention has been given to the important technological development that cleared the way for him. Without it he could not have emerged so startlingly; without it there would have been no modern wood engraving. It is not captious to point out the purely industrial basis for his coming to prominence. Even had he been a greater artist, a study of the technical means at hand would have validity in showing the interrelation of industry and art although, of course, the aesthetic contribution would stand by itself.

But in Bewick's case the aesthetic level is not particularly high. Good as his art was, it wore an everyday aspect: he did not give it that additional expressive turn found in the work of greater artists. It should not be surprising, then, that his work was not inimitable. It is well-known that his pupils made many of the cuts attributed to him, making the original drawings and engraving in his style so well that the results form almost one indistinguishable body of work. The pupils were competent but not gifted, yet they could turn out wood engravings not inferior to Bewick's own. And so we find that such capable technicians as Nesbit, Clennell, Robinson, Hole, the Johnsons, Harvey, and others all contributed to the Bewick cult.

Figure 1. Woodcutting Procedure , showing method of cutting with the knife on the plank grain, from Jean Papillon's Trait de la gravure en bois, 1766.

Figure 1. Woodcutting Procedure , showing method of cutting with the knife on the plank grain, from Jean Papillon's Trait de la gravure en bois, 1766.