W ILLIAM A PPLEMAN W ILLIAMS| A MERICAN R ADICALS |

| A SERIES EDITED BY H ARVEY J. K AYE AND E LLIOTT J. G ORN |

Also available in this Routledge series:

M ICHAEL H ARRINGTON

S PEAKING A MERICAN

by Robert A. Gorman

W ILLIAM A PPLEMAN W ILLIAMS

The Tragedy of Empire

P AUL M. B UHLE

and

E DWARD R ICE- M AXIMIN

First Published in 1995 by

Routledge

29 West 35th Street

New York, NY 10001

Published in Great Britain in 1995 by

Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane

London EC4P 4EE

This edition published 2011 by Routledge:

Routledge

Taylor & Francis Group

711 Third Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Routledge

Taylor & Francis Group

2 Park Square, Milton Park

Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Copyright 1995 by Routledge

Series design by Annie West

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Buhle, Paul, 1944

William Appleman Williamsthe tragedy of empire / Paul M. Buhle, Edward Rice-Maximin.

p. cm. (American Radicals)

Includes bibliographical references (p. 297) and index.

ISBN 0-415-91130-3 (hb : acid-free paper). ISBN 0-415-9113-1 (pb : acid-free paper)

1. Williams, William Appleman. 2. HistoriansUnited States Biography. I. Rice-Maximin, Edward Francis, 1941- II. Title.

III. Series

| E175.5.w55b84 1995 |

| 973.92 092dc20 |

| [B] | 95-19420 |

| CIP |

C ONTENTS

To our days in Madison

We gratefully acknowledge Harvey J. Kaye for his initiative in suggesting this project, and for seeing it through (with the collaboration of Elliott J. Gorn) a change of publishers in midstream. We wish to give our deepest thanks to those Williams family members who gave us their recollections and encouragement in interviews and family documents: Jeannie Williams, Corrinne Williams, Wendy Williams, and Kyenne Williams. Our critics and close readers, who gave us enormously helpful comments, include Alfred Young, Leonard Liggio, David Krikun, Michael Meeropol, Carl Marzani, Michael Sprinker, Jonathan Wiener, Harvey J. Kaye, Allen Ruff, George Mosse, Larry Gara, Elliott J. Gorn, Jim Lorence, Lloyd Gardner, and Bruce Cumings. Mari Jo Buhles contributions significantly reshaped the manuscript. Interviewees especially eager to help us included, in addition to Williams family members, Merle Curti, the late Fred Harvey Harrington, Gerda Lerner, Alan Bogue, Lloyd Gardner, Theodore Hamerow, Thomas McCormick, Peggy Morley, and Peter Weiss. Hans Jakob Werlen supplied us with translations from German scholarly journals. The staff at the Pauling Papers, Kerr Library, Oregon State University, was helpful beyond the call of duty in many ways, but especially in making available all the Williams Papers most expeditiously. Likewise, the staffs at the State Historical Society of Wisconsin; Columbia University, Special Collections; the Nimitz Library; the history department at Oregon State University; and the Jeffries Archive of the U.S. Naval Academy extended every measure of assistance. We received extensive documents, otherwise unavailable, via Brian D. Fors, Mary Rose Catalfamo, Bea Susman, William Preston, Ed Crapol, Scott McLemee, Neil Basen, Henry W. Berger, Lloyd Gardner, Martin Sherwin, Walter LaFeber, William Preston, Karla Robbins, Gerald McCauley, and above all, William Robbins. (Many of these documents, with the permission of the holders, have been subsequently turned over to the OSU collection). Letters and phone calls exchanged with David Noble, John Higham, David Montgomery, Nando Fasce, Peter Wiley, James OConnor, Howard Zinn, Staughton Lynd, Volker Berghahn, Paul Ringenbach, Martin Sherwin, James P. OBrien, Mike Wallace, Paul Richards, Lee Baxandall, James B. Gilbert, James Weinstein, Paul Breines, and Charles Vevier, to name only a few, illuminated many dark reaches of Williamss past. And Christine Cipriani at Routledge polished off the production process. We are grateful to them all, and we hope that our book justifies their faith in our effort.

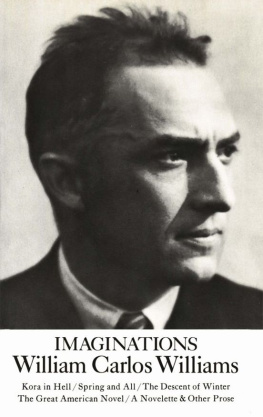

I PREFER TO DIE AS A FREE MAN struggling to create a human community than as a pawn of Empire, wrote historian William Appleman Williams in 1976. Annapolis graduate and decorated Naval officer, civil rights activist and president of the Organization of American Historians, Williams (1921-1990) is remembered as the preeminent historian and critic of Empire in the second half of the American Century. More than any other scholar, he anticipated, encouraged, and explained the attack of conscience suffered by the nation during the 1960s. Radicals have hailed him as a supreme anti-imperialist, while libertarian conservatives have seen him as the second Charles Beard, renewing the perspectives of the nations foremost historian. Fellow historians consider him a great figure in American thought, one who looked for large patterns and asked the right questions. A physically small man with large hands and a wide smile, he seemed indifferent to the abuse heaped upon him from the political mainstream and to most of the praise he earned as well, choosing simply to walk alone.

His Tragedy of American Diplomacy, first published in 1959 and then expanded in subsequent paperback editions destined to reach tens of thousands of readers during the 1960s and 1970s, is probably the most important book ever to appear on the history of U.S. foreign policy. For more than thirty years, scholars have vigorously debated Williamss challenge to the prevailing assumptions. As a key source of dissenting wisdom cribbed by antiwar authors and orators, Tragedy helped frame the public discussion of the U.S. role in Southeast Asia. Williams explained this moral catastrophe as neither misguided idealism nor elite conspiracy but instead as the inevitable consequence of deeply rooted, bipartisan assumptions. Williamss Contours of American History (1961), one of the most influential scholarly books of the age, traced the roots of American expansionism to the nations origins and attributed the rise of the security state with its planned deception of the public to the impossibility of managing a world empire. In these and other volumes, Williams also pleaded for a democratic renewal, a revived citizenship based upon the activities and decisions of local communities rather than upon the demands of a distant welfare-and-warfare state.

Williamss unique insights could be traced to his penetrating economic perspectives and to his long view of modern history. One of his best recent interpreters, Asia scholar Bruce Cumings, describes a twofold process of reading America from the outside in, as those abroad have felt the effects of U.S. policy; and conversely, re-reading the historic documents of U.S. diplomacy for American leaders understanding of the larger world developments at work. Williams framed these insights with his own interpretation of the ways in which distinct social and economic systems evolved, from the rise of modern class society in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to the present. This dual or threefold approach is