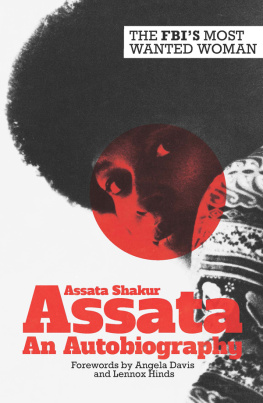

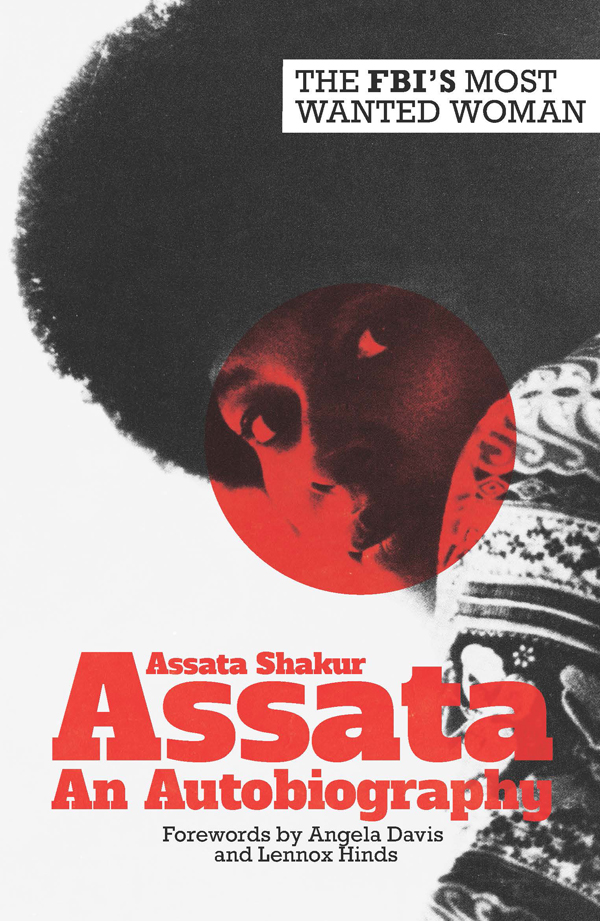

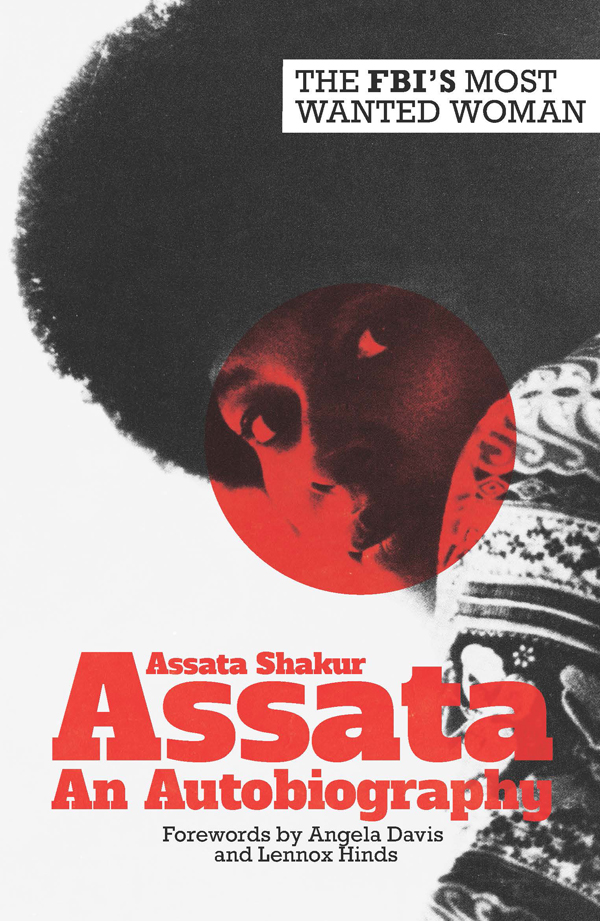

Assata

Assata Shakur is the FBIs most wanted woman. In 1979 she escaped from prison, was granted asylum in Cuba, and has been a fugitive ever since.

Assata

An Autobiography

Assata Shakur

Zed Books

LONDON

Assata: An Autobiography was first published in 1988 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK

This ebook edition was first published in 2016

www.zedbooks.co.uk

Copyright Assata Shakur 1988

Foreword Lennox S. Hinds 1988

Foreword Angela Davis 2000

The right of Assata Shakur to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

Typeset in PT Serif by seagulls.net

Cover designed by Liam Chapple

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78360-178-3 pb

ISBN 978-1-78360-681-8 epub

ISBN 978-1-78360-680-1 mobi

Contents

Foreword by

Angela Y. Davis

In the 1970s, as Assata Shakur awaited trial on charges of being an accomplice to murder, I participated in a benefit at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, to raise funds for her legal defense. At the time, Assata was being held nearby in the Middlesex County Correctional Facility for Men. Lennox Hinds, a member of the Rutgers faculty, had invited me to be one of the featured speakers at the benefit. Lennox was a leader of the National Conference of Black Lawyers and represented Assata in a federal lawsuit contesting the appalling conditions of her confinement in the New Jersey prison. He had previously worked on my case, and we had both served in the leadership of the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression since its founding in 1973. Attending the benefit event were Rutgers faculty members, a sizeable number of black professionals, and local activists who were the mainstay of numerous campaigns to free the political prisoners of that era.

It was an upbeat event, imbued with the optimism of the times. My own recent acquittal on charges of murder, kidnapping, and conspiracy stood as a dramatic example of how we could successfully challenge the governments offensives against radical antiracist movements. However powerful the forces arrayed against Assatathe FBIs counterintelligence program, and the New York and New Jersey police organizationsno one could have persuaded us then that we were not capable of building a triumphant movement for Assatas freedom. This benefit was one small step in that direction, and, as we left the event, we were quite satisfied with the three thousand dollars we raised that afternoon.

By then, every radical activist had learned to assume that our public meetings were subject to routine police and/or FBI surveillance. Yet we were entirely unprepared for what seemed like a reenactment of the 1973 events for which Assata faced charges of murder. Assata, Zayd Shakur, and Sundiata Acoli had been stopped on the New Jersey Turnpike by state troopers who claimed that they had a faulty taillight. The encounter left Assata critically wounded and two othersstate trooper Werner Forster and Assatas friend Zayd Shakurdead. As a group of us left the benefit and drove down a county road toward Lennox Hindss house, where we were having a small after-party, we were quite startled when local police signaled for our car to stop. My friend Charlene Mitchell, at that time the executive director of the Alliance, was told to step out of the car, along with the driver and the other person riding with us. As the policemen taunted us by clearly placing their hands on their holstered guns, I was instructed to remain in the otherwise empty automobile. Lennox, whose car we had been following, immediately doubled back and approached the police with his attorneys identification card in hand, explaining that he was our lawyer. This caused the officers to become more visibly nervous, including one who pulled a riot gun from his police car and proceeded to aim at Lennox from close range. All of us froze. We knew only too well that any innocent gesture could be construed as a reach for a weapon and that this confrontation could easily become a recapitulation of the events that had left Assata with a murder charge.

The spurious explanation given by police for the ambush was a warrant for my arrest (later proven false). Though they allowed us to leave, it was only shortly after we arrived at Lennoxs that we discovered they had already called for reinforcements and literally surrounded the house. With one of the first black woman judges in New Jersey and several other prominent community figures at the house, we were nonetheless compelled to call on higher powers, in the form of Congressman John Conyers in Washington. We figured a request for a federal escort out of the state of New Jersey might put some pressure on the local police. These were the kinds of measuresand friendsneeded in such a volatile time.

I relate this incident in detail because it may help readers of Assatas autobiography not only to focus on the political role of the police during the 1970s but also to better understand important historical aspects of the routine racial profiling associated with current police practices. Such a historical perspective is especially important today when brazen expressions of structural racismsuch as the pattern of mass imprisonment to which communities of color are subjectedare rendered invisible by the prevailing moral panic over crime. And if this were not enough, we find that at the same time such remedies as affirmative action programs and such safety nets as social welfare are being consistently disestablished.

When Richard Nixon raised the slogan of law and order in the 1970s, it was used in part to discredit the black liberation movement and to justify the deployment of the police, courts, and prisons against key figures in this and other radical movements of that era. Today, the ironic coupling of a declining crime rate and the consolidation of a prison industrial complex that makes increased rates of incarceration its economic necessity has facilitated the imprisonment of two million people in the United States. In this ideological context, political prisoners like Assata Shakur, Mumia Abu-Jamal, and Leonard Peltier are represented in popular political discourse as criminals who deserve either to be executed or to spend the rest of their lives behind bars.

During the late 1990s, the racist hysteria directed against Assata was resuscitated when the New Jersey State Police reputedly prevailed upon Pope John Paul II to use the occasion of his first trip to Cuba as pressure for Fidel Castro to extradite Assata. As if this were not enough, New Jersey governor Christine Todd Whitman offered a $50,000 rewardlater doubledfor Assatas return, and Congress passed a bill calling on the government of Cuba to initiate extradition procedures.

In an open letter to the Pope, Assata asks a question that should concern all of us: Why, I wonder, do I warrant such attention? What do I represent that is such a threat? We would all do well to seriously ponder her questions. Why, indeed, was she constructed by the government and mass media as a consummate enemy in the 1970s, only to reemerge at the turn of the century as a singular target of governors, Congress, and the Fraternal Order of Police? What has she been made to represent? What ideological work has this representation performed?

Next page