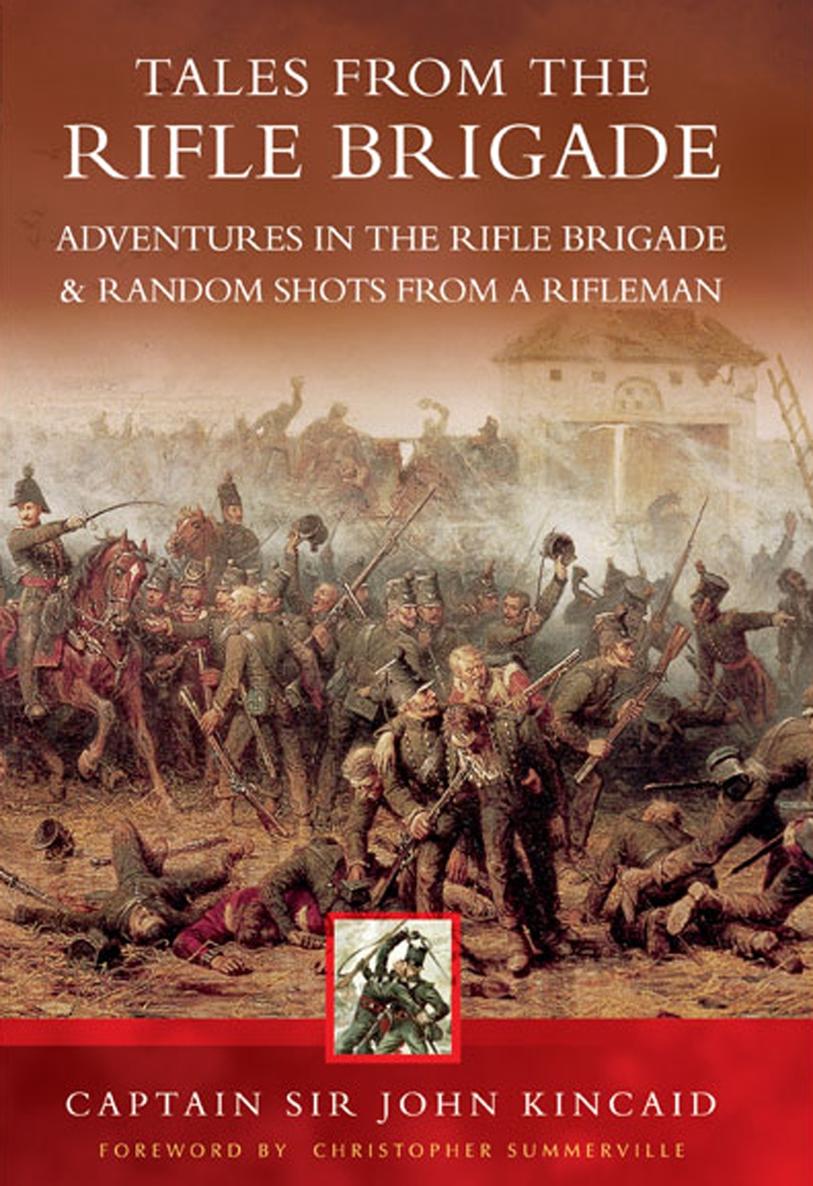

Adventures in the Rifle Brigade first published 1830

Random Shots from a Rifleman first publishe 1835

This combined abridged edition first publish 1909

This edition published in 2005 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

9781783409679

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact:

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England.

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

FOREWORD

Kincaid remembers all the grotesque incidents, ludicrous situations, practical jokes, and misadventures, in which he and his comrades were concerned wrote Sir Charles Oman in 1913. The great historian of the Peninsular War was surveying the cream of Napoleonic reminiscences for his book, Wellington s Army, and goes on to say of Kincaid s lively tales of adventure that they make very good reading and contain all the plums of the cake. Indeed, Kincaid s memoirs ( Adventures in the Rifle Brigade and Random Shots from a Rifleman ) must be among the most stylish, dramatic, excitingand humorousever produced in the genre: they are true classics of war writing.

Captain Sir John Kincaid was born at Dalbeath, near Falkirk, Scotland in 1787. His first taste of military life came with a short spell in the North York Militia, before a more glamorous posting to the lite 95th (Rifle) Regiment in 1809. Kincaid joined the Rifles as a lieutenant and remained with the regiment for the rest of his army career, serving throughout the gruelling campaigns of the Peninsular War, and acting as the adjutant of his battalion at Waterloo. He was rewarded for six years stouthearted service with nine clasps for his Military General Service Medal, a knighthood, and the prestigious appointment of Exon of the Yeomen of the Guard. He died in 1862.

When Kincaid joined the 95th in 1809, it was already one of the most celebrated fighting forces in Europe. It had sprung from the Experimental Corps of Riflemen , formed in 1800 to provide the British Army with a pool of highly professional light infantrymen. These troops were trained to fight both as regular infantry and as skirmishers. A high value was placed on intelligence and initiative among its members, and a code of mutual loyalty and respect fostered between officers and men. Furthermore, these foot soldiers were armed with a new weapon: the Baker rifle. Invented by London gunsmith Ezekiel Baker, this weapon was more accurate than a standard musket, having a grooved or rifled barrel, but required considerable expertise to deploy it quickly and effectively in the field. Consequently, British riflemen received intensive training in its use, becoming superb marksmen in the process. Indeed, it was common practice for men to hold targets for their comrades to shoot at, standing some 200 yards distant. Finally, riflemen were issued with a rudimentary form of camouflage: drab rifle-green uniforms with black belts and facings. Thus the 95th was considered a highly exotic outfit by the redcoats of the Line regiments, while the French, constantly annoyed by their sharp shooting tactics, dubbed them, the rascals in green .

As for the rascals themselves, their motto of first in, last out neatly sums up their experience of war in the Peninsula. In fact, the regiment had fired the first British shots of the Peninsular War, in a skirmish at Obidos on 15 August 1808, subsequently sustaining the first British casualty: a certain Lieutenant Ralph Bunbury. And as the war progressed with ever-increasing ferocity, the Rifles remained in the thick of the action: in an advance, they were at the forefront as skirmishers, sharpshooters or shock troops; in a retreat, they formed a rearguard, keeping the enemy at bay while the army made good its escape. Indeed, as the cream of Wellington s Light Division, the soldiers of the 95th were always at the head of the queue for daring, dangerous, dirty missions.

Kincaid, therefore, was destined to see his fair share of fighting, and armed with nothing more than a light cavalry sabre (better calculated to shave a lady s maid than a Frenchman s head), boldly jumped into the jaws of death with alarming regularity. At the storming of Ciudad Rodrigo on 19 January 1812, he led an assault on the city s ramparts, breaking French resistance at the point of the bayonet in a bout of savage hand-to-hand fighting. Typically, however, having described the heroics, Kincaid takes great pleasure in deflating the situation by taking a swipe at himself:

There is nothing in this life half so enviable as the feelings of a soldier after a victory. Previous to a battle, there is a certain sort of something that pervades the mind which is not easily defined; it is neither akin to joy or fear and, probably, anxiety may be nearer to it than any other word in the dictionary; but when the battle is over and crowned with victory, he finds himself elevated for a while into the regions of absolute bliss! It had ever been the summit of my ambition to attain a post at the head of a storming party: my wish had now been accomplished and gloriously ended; and I do think that, after all was over and our men laid asleep on the ramparts, that I strutted about as important a personagein my own opinionas ever trod the face of the earth; and had the ghost of the renowned Jack-the-giant-killer itself passed that way at the time, I 11 venture to say that I would have given it a kick in the breech without the smallest ceremony. But as the sun began to rise, I began to fall from the heroics; and when he showed his face I took a look at my own; and discovered that I was too unclean a spirit to worship, for I was covered with mud and dirt, with the greater part of my dress torn to rags.

At Badajoz, the following April, Kincaid is again faced with a suicidal assault on a Spanish fortress. In a night attack, the British were obliged to set about storming the city walls with little more than ladders. Rifleman William Green famously described his feelings at the prospect thus: As I walked at the head of the column, the thought struck me very forcibly, You will be in hell before daylight. But Kincaid tells of the esprit de corps among the Rifleshis so-called band of brothersjust prior to the attack:

as the grand crisis approached, the anxiety of the soldiers increased, not on any account of any doubt or dread as to the result, but for fear that the place may be surrendered without standing an assault, for, singular as it may appear, although there was a certainty of about one man out of every three being knocked down, there were perhaps not three men in the three divisions who would not rather have braved all the chances than receive it tamely from the hands of the enemy. So great was the rage for passports into eternity, in any battalion, on that occasion, that even the officers servants insisted on taking their place in the ranks, and I was obliged to leave my baggage in charge of a man who had been wounded some days before.