THE NEW PRESS

NEW YORK

LONDON

2010 by Lynn Powell

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 38 Greene Street, New York, NY 10013.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2010 Distributed by Perseus Distribution

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Powell, Lynn, 1955

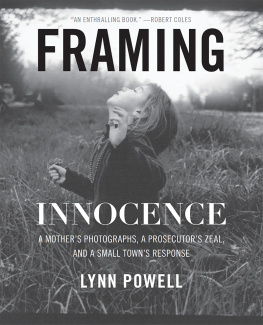

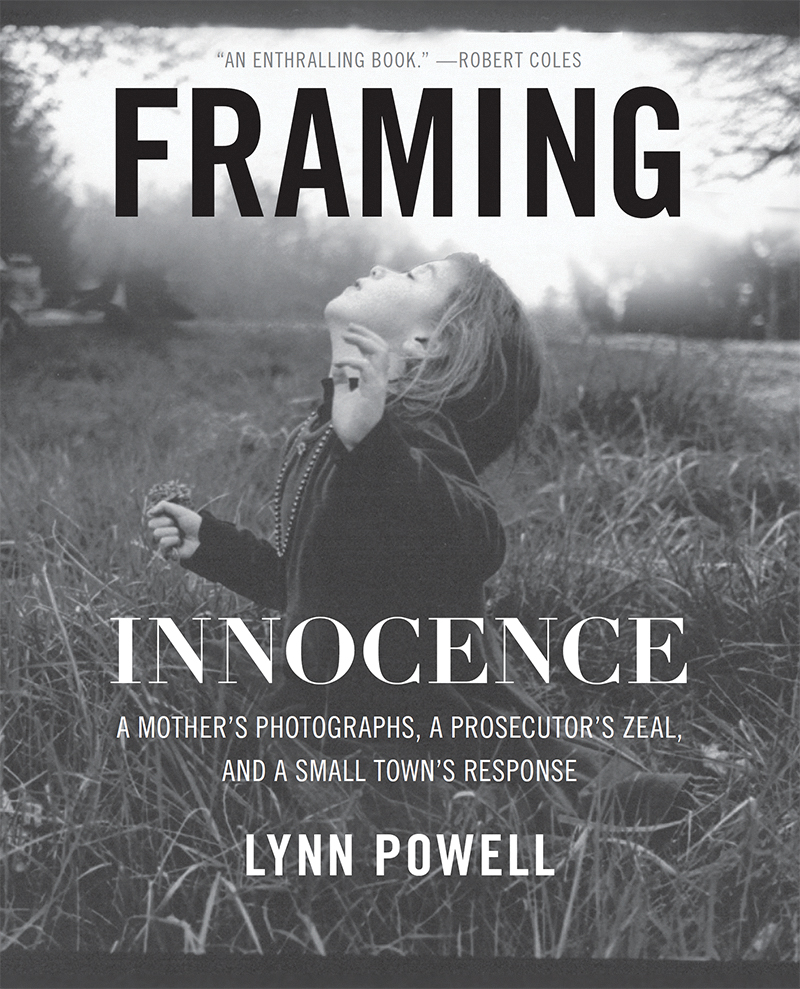

Framing innocence : a mothers photographs, a prosecutors zeal, and a small towns response / Lynn Powell.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-59558-626-1 (hc)

1. Child pornographyOhioOberlinCase studies. 2. Photography of childrenOhioOberlinCase studies. 3. Photography of the nudeOhioOberlinCase studies. 4. Custody of childrenOhioOberlinCase studies. 5. Stewart, Cynthia, 1951- I.

Title.

HV6570.3.O24P69 2010

364.174dc22 2010010894

The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable.

www.thenewpress.com

Book design and composition by The Influx House This book was set in Goudy Oldstyle

For Dan, Anna-Claire,

and Jesse

AuthorS Note

This is a work of nonfiction. I have told this story as accurately and factually as I could. There are no invented scenes and no composite characters. Since this case received local and national media attention and is a matter of public record, I have changed no names, with the exception of the Guardian Angel and Deep Throat. The child at the center of this case is now nineteen years old; both she and her parents have given their permission for this story to be told. All my interviews for this book were tape recorded and transcribed for accuracy.

This book would not have been possible without the generosity of the many people who shared their recollections, notes, letters, e-mails, documents, and opinions about this prosecution with me. And I am indebted to Cynthia Stewart and a number of people who read passages of my work or the entire manuscript to verify its accuracy. Nevertheless, Framing Innocence is my own attempt to make sense of the experiences of an embattled family, and of our community, in the years 19992000. Although this is Cynthia, David, and Noras story, it is my book, and no one asked for or was given approval of the manuscript. I alone bear responsibility for any errors this work may contain.

Snapshot

When my son was three years old, he had a mix-and-match wardrobe of invincibility. Before nursery school each morning, he could turn into Superman, Robin Hood, a lion, a pirate, or a policeman in the costumes I improvised out of old pajamas, swaths of dime-store cloth, and my daughters outgrown tights. But one February afternoon, intrigued by the cherubic boy hed seen on Valentines Day cards, my son shed his clothes, slipped into his sisters room, put on her large, pink fairy wings, and sidled up to me in the kitchen holding his plastic bow and suction-cup arrow. Guess who I am, Mommy! he exclaimed. It was one of those moments when I wanted the world to stand still and let my child always stay so impish and innocent.

I guessed who the little god was, and as he ran off, I called after him, asking if I could take his picture. He agreed. So I stood him before a window where the light streamed in, as if he were indeed an emissary from the clouds. I framed his pink body against the gray sky. Then just as I snapped, I thought, Oh, my God! Could this picture get me into trouble?

I had heard news reports of parents getting arrested for taking snapshots of their naked childrenpictures the parents considered innocent but the police considered obscene. Could the police see my picture as obscene, too?

I looked back through my lens. No, I thought, nobody could mistake this cute picture for porn. I thought of the large hand-colored photograph framed on the wall of our living roommy husbands father as a naked baby lying bottom up on a bearskin rug in 1925. Reassured, I snapped a few more shots of my Cupid.

When I sent off the film to be developed, I did feel a second twinge of concern. But the prints came back on time, and I was delighted with how they had turned out. I knew that someday, when it was hard to recall my sons exuberant nakedness and lopsided wings, I would be grateful to have those pictures. In the meantime, I tossed them into a box of family photos waiting to be put into albums.

A few years later, however, a mother just down the street, the mother of one of my sons best friends, would be arrested for pictures she hadnt thought twice about taking.

PART ONE

The citizens safety lies in the prosecutor who tempers zeal with human kindness, who seeks truth not victims, who serves the law and not factional purposes, and who approaches his task with humility.

Robert H. Jackson,

Attorney General of the United States,

in a speech to federal prosecutors, 1940

1

A Knock at the Door

T he first two photographs of Nora Stewart were taken by her father, David Perrotta, in 1991, on the day she was born. In one, the midwife is hefting and weighing her, as if hefting and weighing a good-sized fish, in the sling of a portable scale. In the other, her mother, Cynthia Stewart, is lying back on a pillow looking exhausted but pleased, with a Gonzos Garage T-shirt pulled up above both of her breasts. The baby is wearing a bright Guatemalan cap. Her eyes are closed, and her tiny hand is half-clenched, with one of her fingers reaching up and almost touching the nipple her mouth is about to latch onto.

Cynthias own first snapshot of her daughter was taken a week later. Cynthias father had come for a visit bearing one of his famous whole-wheat fruitcakes, triple-soaked in bourbon and wrapped in a sheet of Mylar. He presented the cake as Noras dowry, then whisked up his new grandchild and draped her over his shoulder. Cynthia picked up her hand-me-down Nikona parting gift from an old boyfriendand snapped.

By 1999, motherhood had transformed Cynthia Stewart from a casual to a passionate photographer. Early in her daughters life, Cynthia had decided to take pictures of Nora on the last day of every month to record her growth and changes. Soon the photo sessions were weekly. And as Nora grew, so did the reasons to bring out the camera: puddle splashings, tree climbings, tea parties, bubble baths, picnics, birthdays, family friends, playmates, grandparents, fields of wildflowers, sunsets, pets. Nora took Suzuki violin lessons and Scottish dance lessons, played on a city soccer team, sang in a childrens chorus, and performed with a childrens drama troupe. Wherever her daughter went, Cynthia went, too, always with her Nikon around her neck.

Cynthia annotated, numbered, dated, and filed with its negative every photograph she took. Those photos were stored in a few dozen cardboard boxeshatboxes, fruit boxes, shoe boxesstacked in columns against the familys dining room wall. Cynthia dreamed of someday publishing a photojournalistic book that chronicled their familys life. But her larger goal was to bequeath to Nora a photographic memory of her childhood. In the eight years since Noras birth, she had taken a staggering 35,000 photographs. Not all of those pictures were of Nora, but she was in the frame more often than not.