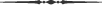

Mark Canepa

LARGE and DANGEROUS

ROCKET SHIPS

The History of High-Power Rocketrys Ascent to the Edges of Outer Space

On the Front Cover

Adriane L. Carbines Triple Threat is prepared for flight at the Black Rock Desert in Northern Nevada. The three-stage scratch-built rocket was launched several times on multiple N and M motors that propelled the vehicle up to 75,000 feet in altitude, followed by successful recovery. Here, Carbine (center, top) descends the launch tower after arming his onboard electronics. Also pictured are Scott Bowden (far right) and Alex Woolner (center, right). Rockets Magazine photographer Neil McGilvray is also shown (left). The high-power launch pad was owned by John Lyngdal. (Photo by the author.)

On the Back Cover

The view from near space: a snapshot from onboard video in a two-stage rocket launched by Kip Daugirdas at the Black Rock Desert on July 4, 2018. His rocket, Workbench 2.0 , was powered by a Cesaroni N2500 in the booster and an AeroTech M685 in the sustainer. It reached an altitude of 154,068 feet and was returned to the ground unscathed. (Photo courtesy Kip Daugirdas.)

Copyright 2019 Mark Canepa.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the author.

ISBN: 978-1-4907-9655-0 (sc)

ISBN: 978-1-4907-9654-3 (hc)

ISBN: 978-1-4907-9653-6 (e)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019910503

Because of the dynamic nature of the Internet, any web addresses or links contained in this book may have changed since publication and may no longer be valid. The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them.

Trafford rev. 10/03/2019

www.trafford.com

www.trafford.com

North America & international

toll-free: 1 888 232 4444 (USA & Canada)

fax: 812 355 4082

Contents

Tripoli Rocketry Officers/Board Members

(19852018)

O n September 20, 2013, Jim Jarvis of Texas propelled a high-power rocket to an altitude of 118,632 feet above the Black Rock Desert in Northern Nevada.

Jarvis, who is neither an aerospace engineer nor an employee of NASA, built the two-stage rocket from scratch in his garage in Texas. The all-black carbon-fiber missile was powered by ammonium perchlorate composite propellant, also called APCP, the same fuel used in the outboard boosters of the space shuttle. Together, the two motors in the rocketone in the booster and the other in the second-stage sustainergenerated nearly 3,000 pounds of thrust.

Within seconds after the 90-pound rocket cleared its homemade launch pad, which was made from sections of metal available at Lowes or Home Depot, the missile was traveling more than 750 miles per hour. Thats faster than the speed of sound. Moments later, as the rocket streaked into the stratosphere above 30,000 feet, it was traveling at Mach 2twice the speed of sound or nearly 2,000 feet per second. Thats faster than a rifle bullet.

In less than 60 seconds, Jarviss rocket was nearly halfway to space, more than 100,000 feet high. At apogee, the highest point in the flight of a rocket, the rocket was turning over now, slowly, as the grip of the earths gravity overcame the vehicles forward momentum. Now if everything went as planned, onboard electronics would activate a recovery system designed by Jarvis to return his rocket safely to the ground so that it could be flown again.

His rocket vanished high in the sky above, Jarvis had nothing more to do. Now all he could do was wait. Soon, he would find out whether he still owned a rocket or just another hole in the desert.

Forty years ago, a hobby rocket flight to more than 100,000 feet was unthinkable. Higher-power rocketry was not much different from model rocketry. Rockets were small and lightweight and propelled by motors designed to lift a model rocket to an altitude of up to 1,000 feet or maybe just a little bit higher. There were no reloadable high-power motors, no onboard altimeters or sophisticated electronics, no reliable recovery equipment. There were also no advanced materials from which to build lightweight, durable airframes capable of withstanding the forces generated in modern high-power rocketry. All that was still science fiction. There were just small hobby rockets with colorful plastic parachutes.

Yet beginning in the mid-to-late 1970s, hobby rocketry began to evolve from just another branch of the toy industry into a modern tour de force of Space Age fuels, advanced electronics, and high-performance recovery gear. In the ensuing three decades, people from every walk of life, most of them far removed from the professional sciences, created an international organization devoted to the limitless pursuit of citizen-based rocketry. These flyers destroyed thousands of rockets along the way to the upper atmosphere, grappling with the immutable laws of chemistry, engineering, and physics in attempts to send their homemade projects tens of thousands of feet into the air.

To protect their freedom to fly such rockets, flyers sometimes did battle with local authorities, state legislatures, and even the federal government. Sometimes they even battled one another.

This purely civilian journey to the edge of the upper atmosphere began at a time when Americas space program was in retreat. The Space Race with the Soviet Union, which ended with the landing on the moon in 1969, captivated young people all over the world, perhaps nowhere more so than in the United States. In the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of young Americans took to their local playgrounds and parks to launch model rockets. Using small black-powder motors, young people fired off their little missiles to several hundred feet or so and then watched them drift back to Earth under parachuteimaginary astronauts returning from their landing on the moon.

After the last Apollo mission to the moon in 1972, there was a decreasing political interest in manned space travel. Yet at almost the same time the Space Race became yesterdays news, hobbyists discovered a new and more powerful means by which they could send their homemade rockets higher than ever before. A new propulsion source known as the APCP motor found its way into hobby rocketry. By the late 1970s and beginning in the remote deserts of Southern California, fledgling commercial motor makers working out of ordinary garages began manufacturing and distributing this modern propellant to enthusiastic hobbyists all over America. Starting with a small and very modest selection of rocket motors, these manufacturers grew their product line to include motors of incredible size and power, creating in their wake an entirely new rocketry hobby, one that went far above and beyond model rocketry. This new hobby was called high-power rocketry.

In the 1990s, high-power rocketry spread throughout the United States and then the world. Today high-power vehicles can carry onboard altimeters, GPS tracking units, and enough propellant to break Mach 1 in seconds. They can be flown in configurations that include small handheld rockets that may reach 5,000 feet at a cost of $50, sophisticated midrange missiles that weigh up to 100 pounds and can clear 20,000 feet, or modern-day technological works of art that cost only a few thousands of dollars yet travel higher and faster than any aircraft in any air force in the world. This hobby is now poised to send vehicles to the very edge of space and perhaps even beyond.

Next page

www.trafford.com

www.trafford.com