Prologue

The Struggle for Equality

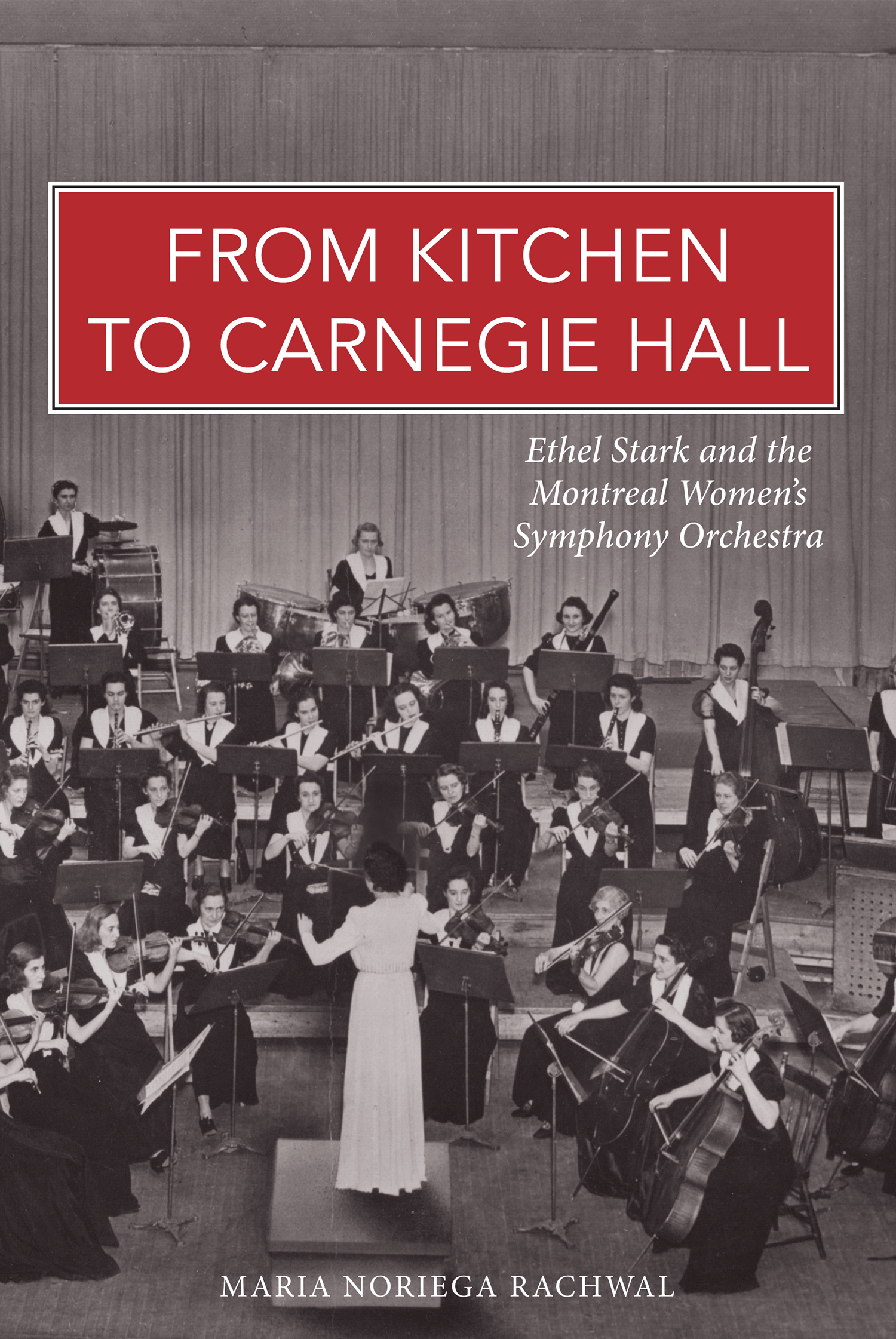

Today men and women perform side by side in symphony orchestras all over the world, but from its conception in the eighteenth century, the symphony orchestra had been an all-male bastion, a trend that persisted through much of the twentieth century. This elitist tradition systematically excluded women from participating in the creation and performance of symphonic music on the public stage. With the exception of the harpist, who sat almost invisibly on the wings of the stage, professional orchestras in North America and Europe would not hire female musicians, and if they did so, it was reluctantly and usually only until a male replacement could be found. The shortage of equal opportunities for female musicians was the same everywhere in the Western world New York, Philadelphia, Montreal, Berlin, Vienna, London. Orchestras remained boys clubs where no women were wanted.

Ironically, women were encouraged to study music in order to enhance their marriageability and their chances of moving up the social ladder. Taking music lessons, along with painting, embroidery, and cooking, was considered a part of the proper education of an accomplished lady of good social standing. But this is as far as women were encouraged to pursue any musical aspirations. Their music-making was deemed appropriate only in the private sphere, where their fathers, husbands, and relatives could monitor their activities. Women were encouraged to be proficient at their instruments but not so accomplished as to threaten male talent.

With the exception of singers, careers for female musicians were limited to teaching music lessons to boys and girls, which was essentially an extension of their motherly duties in the domestic sphere. In the late nineteenth century some colleges in North America began to accept female pianists into their programs. Some of the first women who played in public were pianists who graduated from these institutions. Others were child prodigies whose extraordinary talent propelled them onto the international stage. Teresa Carreo, Marguerite Long, and Maud Powell are but three examples. Still others were the wives, daughters, or sisters of famous musicians, such as Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, Clara Wieck Schumann, and Camilla Urso. But these women were the exceptions, not the norm.

Furthermore, prevalent rules of etiquette dictated that only certain musical instruments were acceptable for women those that enhanced their feminine appearance. Keyboard instruments, the harp, the lute, and the guitar, not only highlighted a womans dainty hands, but also required her to sit for long periods of time, reinforcing a kind of domestic ideology that bourgeois society promoted: woman as passive, submissive, and socially muted. The idea of women performing on traditionally male instruments, like the cello or double bass, was a deep source of controversy. Given North Americas prudish conventions at the time, it is not surprising that a players choice or rejection of an instrument often depended on the sexual metaphors evoked by the instrument itself. The curves of the violin, for example, alluded to the female hourglass figure and when played by a man emphasized the male superiority over the female and woman as the object of mans desire, herself an instrument of pleasure.

By far the most challenging instruments for women to justify playing were the woodwinds, brass, and percussion. These instruments not only had strong military connotations, thus making them indecent and unbecoming for women, but they also required the distortion of facial features. Puffing on a tuba, forcing air through a bassoon, pressing the lips to play a clarinet, or flushing the face in trying to get enough air into a French horn was expected of men but thought highly unflattering to women. In his 1904 article, Opinions of Some New York Leaders on Women as Orchestral Players, Gustave Kerker, a prominent musical director on Broadway, wrote,

Nature never intended the fair sex to become cornetists, trombonists, and players of wind instruments. In the first place they are not strong enough to play them as well as men; they lack the lip and lung power to hold notes, which deficiency makes them always play out of tune. Another point against them is that women cannot possibly play brass instruments and look pretty, and why should they spoil their good looks?

Magazines of the early twentieth century suggested how women could look their best while playing musical instruments, while others encouraged them to keep to traditional instruments for the sake of their good looks. Because the image of proper, graceful femininity declined in direct proportion to the size, harshness, and volume of sound produced by an instrument, a woman playing a violin was more tolerated than a woman playing a double bass, and a female flutist was preferred to a female tuba player. Though in reality, none of them were really accepted, simply tolerated for the temporary novelty they created.

The idea that women could play the orchestral music of the great masters as well as men would have been received with contempt or disbelief. Likewise, black musicians male or female were also excluded from the roster of the symphony orchestra because blacks, like women, were considered too irrational (or feminine) to play this exclusive collection of concert music.

The idea of a female conductor was even more ludicrous; indeed, it seemed almost impossible. Commentators who even entertained the idea considered conducting to be too physically and mentally demanding for most women. There was also the lingering prejudice against womens leadership. In the 1940s, a fourteen-year-old girl asked the editor of a music magazine, a former professor at the renowned Oberlin Conservatory in Ohio, Why is it that nobody has ever seen or heard of an orchestra leader that is a woman? The professor replied, Men dont like to play under a woman conductor[and] people generally dont have as much faith in a woman conductor as in a man. Like alcohol and driving, home-making and leading an orchestra do not go together very well, and I myselffeel that this is all right. The question of why women were excluded from symphony orchestras has been debated in many accounts of the history of women in music. There were many reasons for their exclusion, but the underlying theme was one of power and control. At the heart of these biased practices was the fear that allowing women into such a traditionally male institution would also weaken other structures of male privilege.