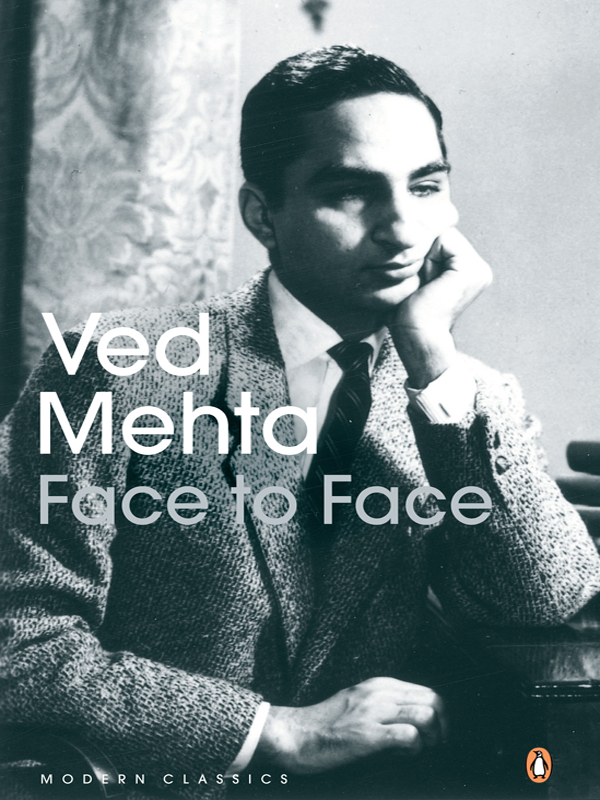

VED MEHTA is the author of twenty-seven acclaimed books of fiction and non-fiction. He was born in 1934 in Lahore and educated largely in the USA. A staff writer on the New Yorker from 1960 to 1993, he has won many awards and is a fellow of Balliol College, Oxford, and the Royal Society of Literature. Mehta lives in New York.

Praise for the Book

Brilliant as a ray of sunshine piercing darkness, the warmth and modesty, the humor and sensitivity of young Ved Mehta light his story all the way throughNew York Times

An un-self-pitying, dry, acutely observant autobiographySunday Times (London)

[The book] testifies to astonishing bravery and tenacityGuardian

There are no heroics, no underlying self-congratulation. Simplicity, freshness and objectivity are more than the style of the book. They are the roots from which this record of fortitude draws its powerEconomist

It is more an intimate conversation than a formal literary efforthuman, humorous and penetrating on a wide variety of subjectsLos Angeles Mirror

His book leaves you guessing, but its fine quality is that you are guessing with a high heartNew York Herald Tribune

A brave book. The blind author has extraordinarily vivid powers of description... He lights up for his readers the world he cannot see himselfIllustrated Weekly of India

This book is not simply an account of the personal experiences of one blind man. The Hindu family and the terrors of Partition, the volatile atmosphere of the Little Rock School, the pathetic story of a Japanese friend at Collegehis skill makes all this vivid, and he has sympathy to spare for the sufferings of all sorts of other people, including the Muslims who dispossessed his familyBalliol Annual Record

This entire book was dictated to my two fellow students, JoAn Johnstone (Pomona 1956) and Grace Kestenman (Radcliffe 1957); my labor was made easier by JoAns patience and understandingnot to mention her well-cooked lunchesand Graces cheerful and alert personality. The devoted and unsparing work of Nancy Reynolds (Atlantic Monthly Press) was invaluable in preparing and brushing up the manuscript for publication. Another good friend to whom I am deeply indebted is my sponsor, for it was her timely and generous help that made it possible for me to write at all.

Balliol College

Oxford

15th October, 1956

Ved Mehta

For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

I CORINTHIANS 13: 12

Foreword

About three Christmases ago, I was invited by a group of students to speak on India. We want, the invitation read, something with flesh and blood, something which is more than just a talk on day-to-day happenings in your country.

I rummaged through my file of previous talks, but none of them seemed to fill their order. The longer I sat by my Braille-writer, the harder it became to produce what was required. I was about to write and decline the invitation when one of my friends suggested that I use the form of a fairy story, but buttress it with real, live stuff. I returned to my Braille-writer, and beginning with the sentence, Once upon a time there was a salt march led by a frail little man, I constructed a success story of Indias struggle for independence, complete with description, dialogue, action and pathos.

Full of trepidation I delivered my talk, but from the reaction it seemed that the teen-agers had not lost their appetites for fairy stories. At the close of the discussion period a young lady on my right asked, Have you ever written anything?

From the back of the room a boy piped up, It would be hard for him to write, an allusion probably to my blindness.

This challenge, along with that speech, was the germ of the present narrative. The real, live stuff. I knew best was my own experience, yet I realized even before I began to write (I was then twenty) that no one mans experiences or reflections were sufficient to justify or inspire a book. But India, where I had been born and brought up, was. In that land there were color, splendor and pageantry, juxtaposed with tragedy, division and change. I was all too conscious of my own limitations, but with the solace that everyone had to begin somewhere, I set that summer aside to write, for my own diversion.

I began by trying to re-create a house of India, with all its colorful awnings, and portraits of family members, servants and pandits, and even the Kiplinglike curios which decorated the mantelpiece. In a way it was easier to build this house because its original had been drowned in the fast current of contemporary history. It seemed natural, then, to go on to describe the whirlpool of events which had divided my country.

After the intensive writing of that summer, I went back to the routine of a student until two years later, when with the kind encouragement of Mr Edward Weeks, the project was resumed. But before the book would be complete I would have to write a section on the United States, where I had been living for seven years.

This I undertook with mixed emotions. It would not be hard to write about a country to which I owed so muchmy education and the use of the very language which made this book possible. And yet so many people had written about America, and with a much more eloquent pen and perceptive eye than I could ever command, that I wondered if I had much to offer that was fresh and worth being on a readers bill of fare. Although the first two parts had to reflect larger issues, I decided that this final section should be wholly personal in tone.

And so I wrote about the experiences of a boy totally blind, set loose alone in the vast and bustling United States at the age of fifteen. The third part, then, is the story of the reception, problems and growth of this blind boy until he reached manhood, and of the pleasures and warm friendships he experienced in the West. Actually, the narrative is a succession of images, images collected from old and new Indiaone eclipsed, one risingand from America, as these images appeared to that boy in the time of his growth.

1

Surmas and School

In India as elsewhere every girl or boy has fond and warm memories of his childhood, from the day he begins to talk to his mother and father in broken syllables. Invariably a child learns and recognizes the faces of his mother and father, of sisters and brothers who play with him constantly, or the servants who prepare his meals or watch him play in a nursery strewn with knickknacks and toys. He must also remember the rich colors of the butterflies and birds which children everywhere always love to watch with open eyes. I say must, because when I was three and a half, all these memories were expunged, and with the prolonged sickness (meningitis) I started living in a world of four sensesthat is, a world in which colors and faces and light and darkness are unknown.