Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

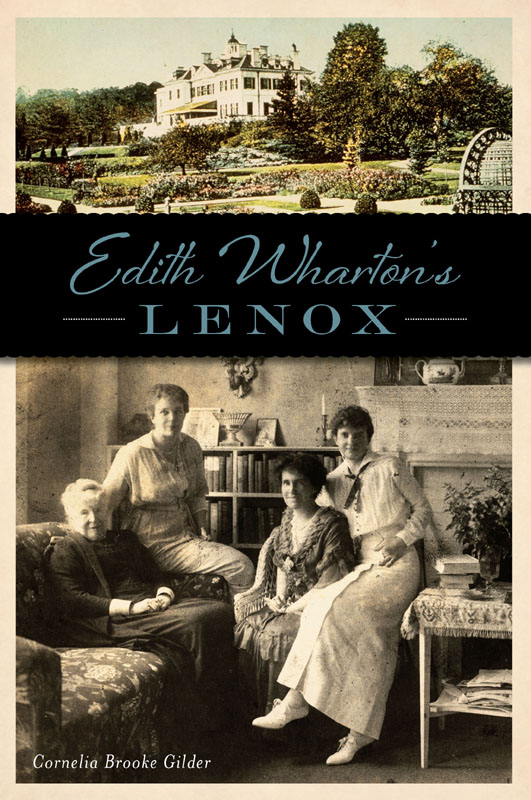

Copyright 2017 by Cornelia Brooke Gilder

All rights reserved

First published 2017

e-book edition 2017

ISBN 978.1.62585.788.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931824

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.517.7

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Louisa, Nannina and George

Contents

Acknowledgements

This book evolved from a decade of conversations in the 1990s on Thursday mornings with my invalid mother, Louisa Ludlow Brooke, and her friend and retired librarian Julia Conklin Peters. They were both in their eighties and vividly remembered Lenox after Edith Whartons departure in a way no research on the Internet or in archives could provide.

Since then, how can I name all those who have helped piece this story together? I often looked back at old notes of conversations with the late Scott Marshall of The Mount staff and wish he could see this book. Many provided a specific detail or image, and their names are buried in footnotes and photo credits. Others had their specialties. Any question about coaching or horses could be answered by Mary Stokes Waller; about fashion (important for dating photos), Sarah Goethe-Jones; about Newport, Paul Miller; and about Pau, David Blackburn. My daughter Louisa Gilder provided perceptive canine points, but that was only part of her incredible contributions linking Ediths writings to my narrative. Others added key perspectives in more general ways, like our old plumber Findlay MacLean; my mother-in-law, Anne Palmer; Susan Wissler; Anne Schuyler and Marjorie Cox at The Mount; John Brooke; Nina Ryan; Deborah Coy; Doug Bucher; Charlie Flint; Robbie Harold; Ned Perkins; Barry Cenower; Jennie and David Jadow; Julia Channing Bell; Christina Alsop; Kate Auspitz; Susan Lisk; Sophie Howard Palmer; Holly Ketron; Jean-Claude Lesage; and Steve OBrien, Lenox police chief. The staff of the Local History Department at the Berkshire Athenaeum have creatively solved many a strange genealogical or historical question that I brought to them in distress.

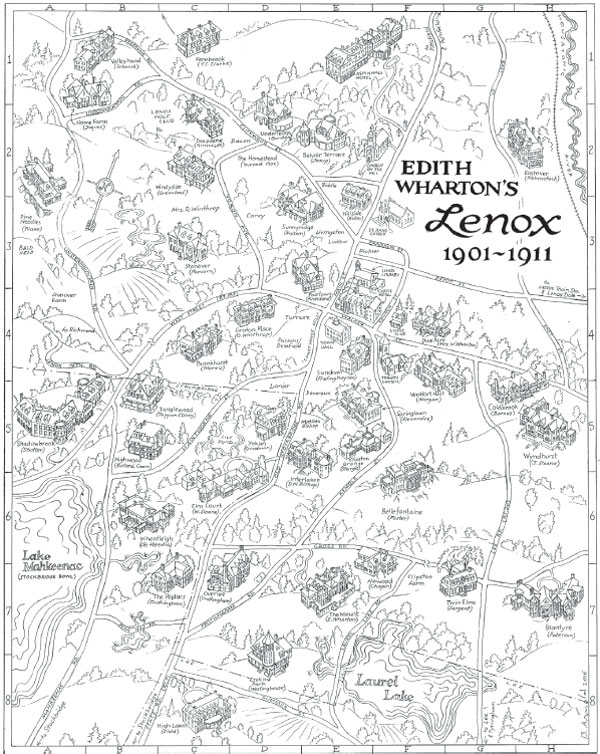

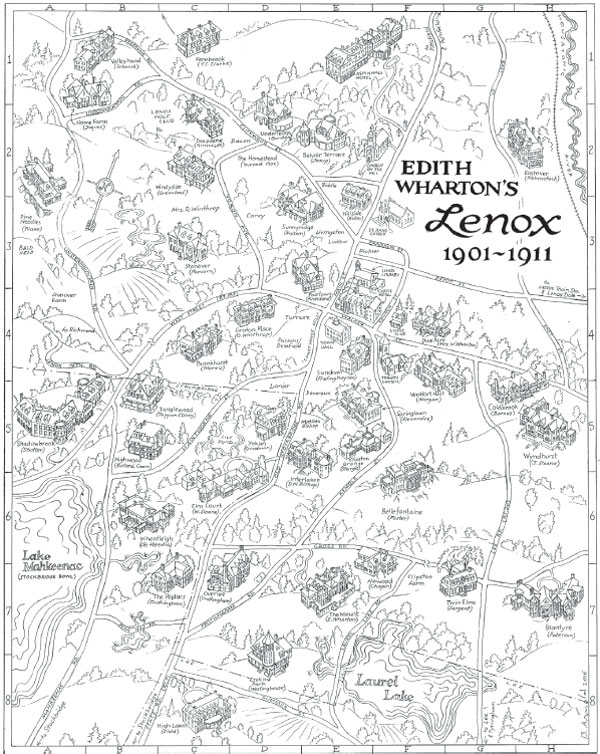

The quest for historic images is a huge component of a book like this. Of the hundred-some photos, one-third came from the wonderful scanned collection in the care of the unsung heroes of the Lenox Library, director Amy Lafave and librarian Christy Cordova. The rest of the images are from so many sourcesoften fragile, private albums, requiring a level of photography and scanning skills that I did not have. My calm and capable daughter Nannina Stearn came to the rescue. Lenox artist Bart Arnold has created the exquisite map evoking Edith Whartons era in a way that surpasses any words.

Wharton scholars Alan Price and Irene Goldman-Price helped to shape and improve this work in so many ways. Other early readers of the manuscriptTjasa Sprague, Richard S. Jackson Jr. and Cris Raymondeach made valuable corrections and suggestions. Tabitha Dulla, Karmen Cook and now the unruffled Chad Rhoad of The History Press staff each nudged this project along over the last two years. Thank you all!

Finally, thanks to George Gilder, my writer-husband, who sets high standards for us all and provides generous and loyal support to all we do. Four of his great-grandparentsRichard Watson Gilder, Helena deKay Gilder and Adle and Robert Chapinenliven the pages of Edith Whartons Lenox.

The authors mother, Louisa Ludlow, surveys Main Street from her pram. Her older brother, Richard, has relinquished his carriage to the family Scottie. Fall 1910. James B. Ludlow.

Introduction

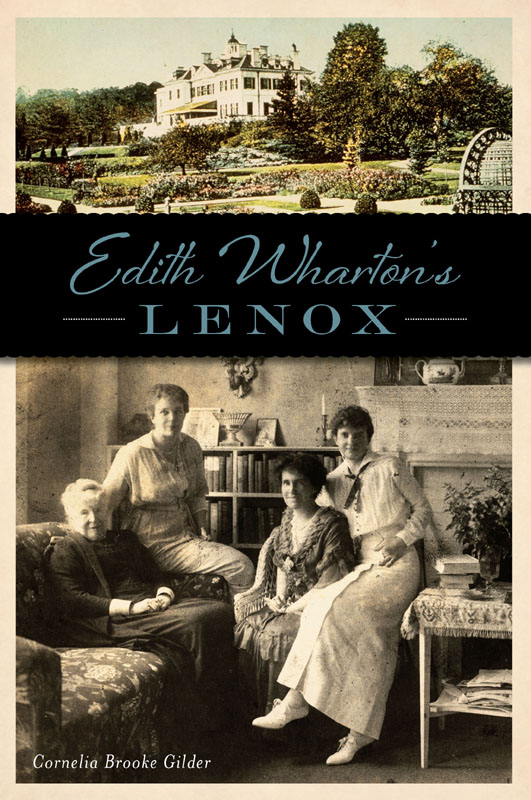

In tackling her long and complicated life, Edith Whartons biographers have often glossed over her connections to the Lenox community, where she and Teddy settled in 1900. The biographers have the perfect excuse: the brilliant writer preferred to import her own company. This idea is followed by the assertion that the Lenox social circle was not worthy of her.

By the early 1900s, Lenox was a well-established resort with an intellectual history. A graceful New England village in the hills of western Massachusetts, it was neither a mill town nor a market town but a former county seat with noble colonial architecture and tree-lined streets frequented fifty years earlier by the shy Nathaniel Hawthorne working out the plot of The House of the Seven Gables. Since then, the resort had grown and attracted urbane and cultivated familiesmainly New Yorkers and Bostonianswith leisurely pursuits ranging from collecting rare books or Belgian lace to breeding Jersey cattle or Japanese spaniels.

Edith Wharton would not be the first talented woman writer in Lenox. From the 1820s on, novelist Catharine Sedgwick (17891867) was the center of a salon and a revered local icon. Her celebrity friend Fanny Kemble (18091893), a Shakespearean actress by financial necessity but an author and poet by inclination, frequented Lenox through the 1870s. Well acquainted with British and American country life, Fanny Kemble particularly enjoyed the Lenox atmosphere, where we ride, drive, walk, run, scramble and saunter and amuse ourselves extremely. As Fanny faded from Lenox, Constance Cary Harrison (18431920) arrived. She was a southern belle who enchanted Lenox in the later 1870s, 80s and 90s with a stream of novels (often set in Lenox) and plays (often translated and adapted by her from French). Harrison produced these plays in the summertime on the Sedgwick Hall stage at the Lenox Library, mixing local talent with professionals before taking them to the Madison Theater in New York City.

Bart Arnold, 2017.

The Lenox social set already knew the sporting, well-dressed, amiable Teddy Wharton, who had spent some twenty summers there since his teenage years. But Teddys clever, sophisticated, younger wifestill an obscure short story writer and architectural criticwas an enigma, certainly not the conventional Mrs. Edward Wharton they might have expected.

Buoyed by the bracing climate and less-pompous social atmosphere, Edith welcomed Lenox after Newport. She immediately entered into local social occasions. (She preferred small lunches and teas to big gatherings.) She competed in flower shows and brought her vision to local institutions, especially the Lenox Library (walking up the same worn marble steps we use today) and the French Reading Room in Lenox Dale. She would find herself in the midst of the inevitable mix of kindred spirits, imperious grande dames, delightful eccentrics and inescapable boresall wonderful fodder for a fiction writer.

Next page