Text copyright 2019 by Chronicle Books LLC.

Images copyright 2019 by the individual licensors.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 9781452169071 (epub, mobi)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Names: Barter, Judith A., 1951- contributor. | Roe, Sue, contributor. | Farrugia, Mallory, editor.

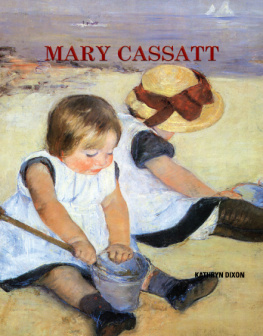

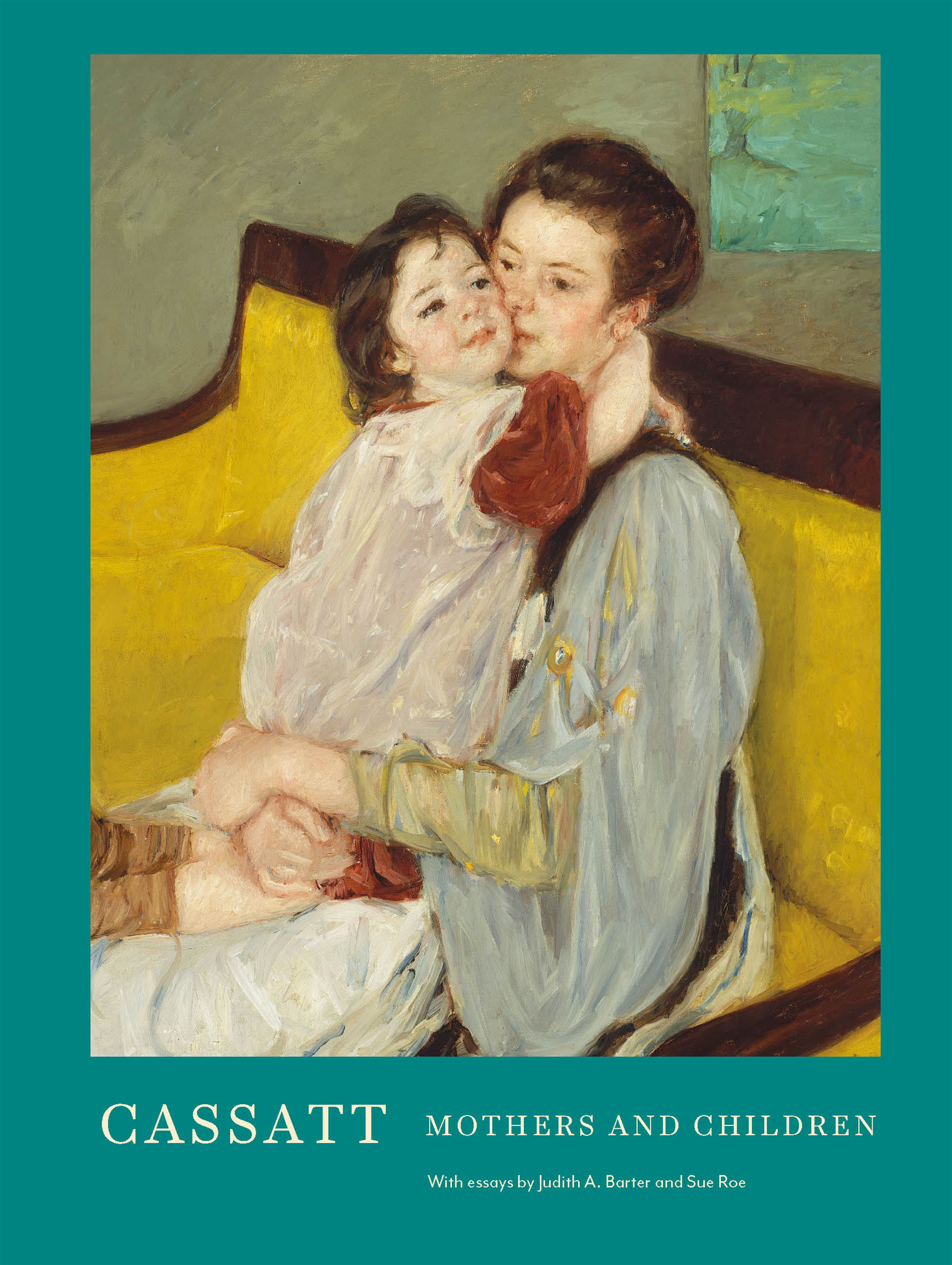

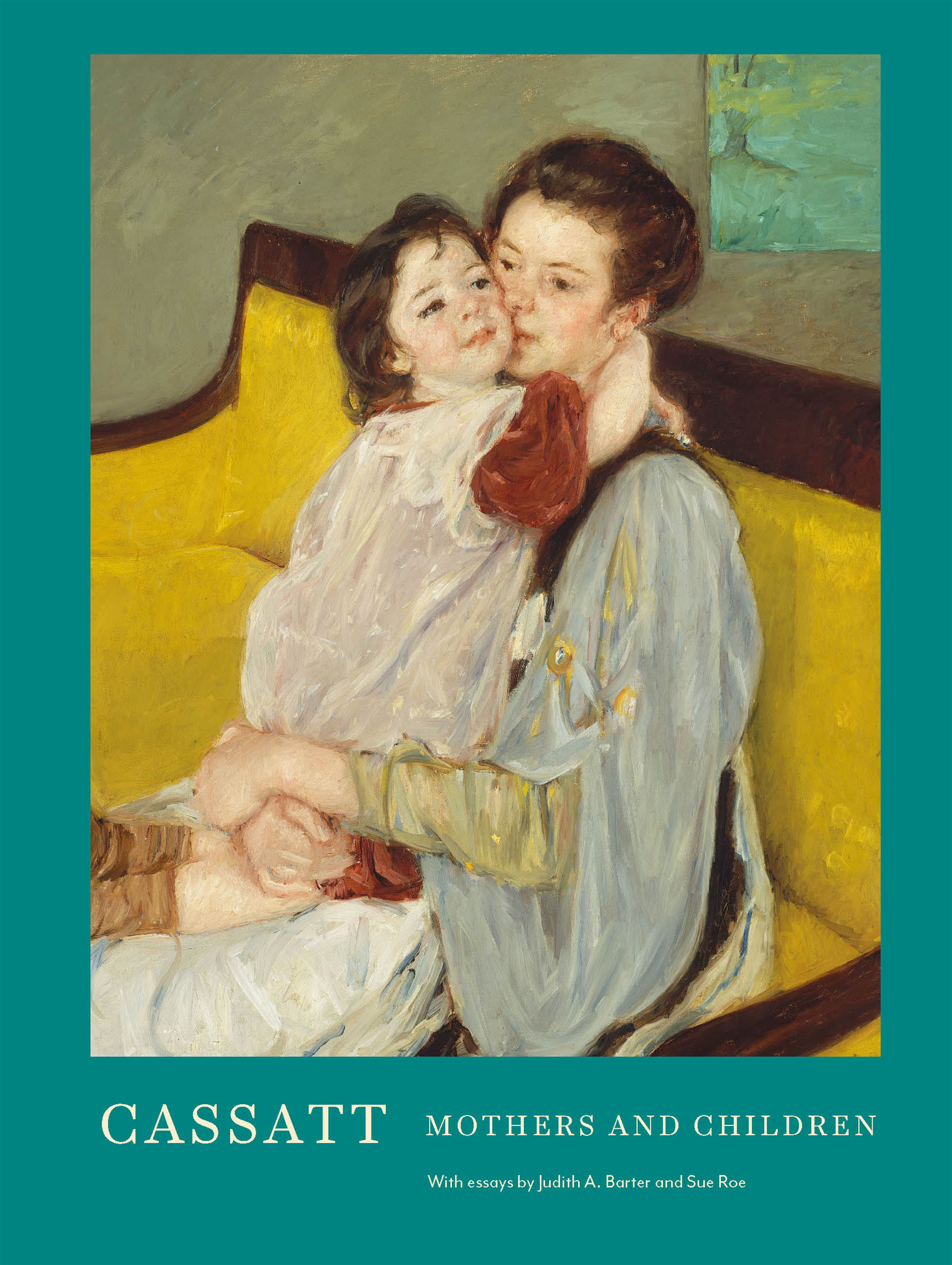

Title: Cassatt : mothers and children / with essays by Judith A. Barter and Sue Roe ; picture editor: Mallory Farrugia.

Other titles: Cassatt (Chronicle Books (Firm))

Description: San Francisco : Chronicle Books, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018047201 | ISBN 9781452169033 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Cassatt, Mary, 1844-1926--Criticism and interpretation. |Mothers in art.

Classification: LCC N6537.C35 C375 2019 | DDC 759.13--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047201

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at or at 1-800-759-0190.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

CONTENTS

Judith A. Barter

Sue Roe

MARY CASSATT: MATERNITY AND MODERNITY

Judith A. Barter

Field-McCormick Chair and Curator Emerita of American Art

The Art Institute of Chicago

Mary Cassatt, along with James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent, was one of the most important expatriate American artists of the nineteenth century. More remarkable still, despite being a foreigner and an unmarried woman, she was at the center of the Parisian avant-garde artistic circles of the 1870s, 80s, and 90s. Cassatt turned those perceived deficits into advantages. An intrepid traveler, she studied extensively in Italy, Spain, and France, facing obstacles with a tenacious spirit and a superior intellect. Standing five-and-a-half feet tall, with brown hair, gray eyes, a snub nose, a wide mouth and chin, and a ruddy complexion, she was not a beauty, as Edgar Degass portraits of her attest. But her electric vitality, described by her artist friend George Biddle, and the keen intelligence she possessed made her attractive to those who met her, and in her time, a talented modern artist.

Cassatt arrived in Paris accompanied by her sister Lydia in 1874, believing that Paris was the center of the art world and where she needed to be in order to make her living as a professional painter. The sisters experienced the nightlife of Paris, and Cassatt painted evenings at the opera and the parade of fashionable theatergoers. She embraced the spectacle of the modern world, and especially the qualities of light so favored by the Impressionists. In her opera pictures she included reflecting mirrors, ocular devices such as opera glasses, and chandeliers. Her pictures of reflections in mirrors predate douard Manets famous A Bar at the Folies-Bergre by several years.

She met Edgar Degas perhaps as early as 1875, and made her debut with the Impressionists in 1879 when her loge, or box, pictures were first shown. But even at this early date, Cassatt was drawn to the intimacy of domestic scenes as well. Her Portrait of a Little Girl, 1878 (National Gallery), rejected by the Paris Salon, depicts the innocent informality of childhood. The child (the daughter of a friend of Degas) is flopped in the armchair across from Cassatts dog. Naturalism and sensuality of a pure, elemental, and nonsexual kind fill Cassatts depictions of childhood. Perhaps such physicality and the childs insouciant sprawl made some uncomfortable. It is a description of a child thinking, between rest and play. The drawing room is rendered in the colorful shorthand of Impressionism, and the flattened picture plane shows the influence of Japanese prints so valued by the Impressionist circle.

In fact, Cassatt emulated Japanese prints in her famous suite of color prints executed in 1891. Deeply impressed by Japanese prints shown in Paris by the dealer Siegfried Bing, she began her own series of color drypoints and aquatints. The print series was physically demanding; sometimes she and her printer worked eight hours a day. She drew an outline on one plate in drypoint and then transferred this image to two other plates, for a total of three platesnever more. She then put aquatint wherever the color was to be printed and painted the ink directly on the plate. The print series emulated her themes of the 1880s, and contained a childs bath, women and a child on the omnibus, and children snuggling with women, as well as intimate domestic scenes of women bathing, taking tea, trying on dresses, and writing letters. The intimacy of these scenes as well as the pastel shades and abbreviated, beautiful draftsmanship have made Cassatts color prints justly famous.

Cassatt showed with the Impressionists until the last group exhibition in 1886. Many of her colleagues moved to the countryside, as did she. Her work began to change, even if some themes did not. Other art produced by her contemporaries at this time included the Postimpressionism of Paul Gauguin and his studies of Brittany peasants, the mythical and symbolic work of Maurice Denis, and the classicizing murals of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Cassatts themes of womanhood and childhood took on new meaning and monumentality.

She worked in pastel, as well as oil and prints. The pastels often contain rough parallel strokes and intense, rich colors. Looking carefully, one can find a fingerprint where the artist worked the pastel into the wove paper. Mothers and children are tenderly entwined. Often children are nude, showing their close relationship to unvarnished simplicity and to Cassatts Spiritualism. This belief system tied her closely to the natural world. Spiritualists believed that children come into the world in purity and innocence, and that God can be approached through nature. In her oil paintings of the 1890s, gardens, flowers, and natural motifs are important. Figures become larger and often seem to be in contemplation. At this period, Cassatt turned away from the earlier Impressionist themes and to other sources for inspiration. For example, The Family (1892) takes the poses of mother and children directly from Renaissance master Sandro Botticellis Virgin and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist, which Cassatt saw at the Louvre. She increasingly painted women and children in outdoor settings, echoing Cinquecento poses, and emulated the dry, chalky surface of these unvarnished Italian paintings.

The Renaissance themes of Madonna and child provided Cassatt with rich material for her evolving theme of women and children as the primary procreative element in society. Because she was unmarried and childless, some critics see her work as longing. But it is important to understand that Cassatt was an independent woman and supported suffragettes and feminismor the NewWoman, as such females were called. In French society, wives and children were the legal chattel of husbands. Divorce was not legal in France until 1884. The Camille Se Law establishing lyces, or schools, for the education of girls was introduced in 1880. While French women still could not vote (until after World War II), the idea that women were the moral arbiters of the home and the family slowly took hold. As such, many feminists, and Cassatt, believed women to be the superior sex. Indeed, writing to her friend Louisine Havemeyer during World War I, Cassatt opined that men had made a mess of the world and it was time for women to make the decisions. That Cassatts modern political views evolved alongside her feminism is apparent in her lending works to the Benefit of the Woman Suffrage Campaign exhibition at Knoedler & Company in New York in 1915. American women received the vote in 1920.

Next page