CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Target for Today

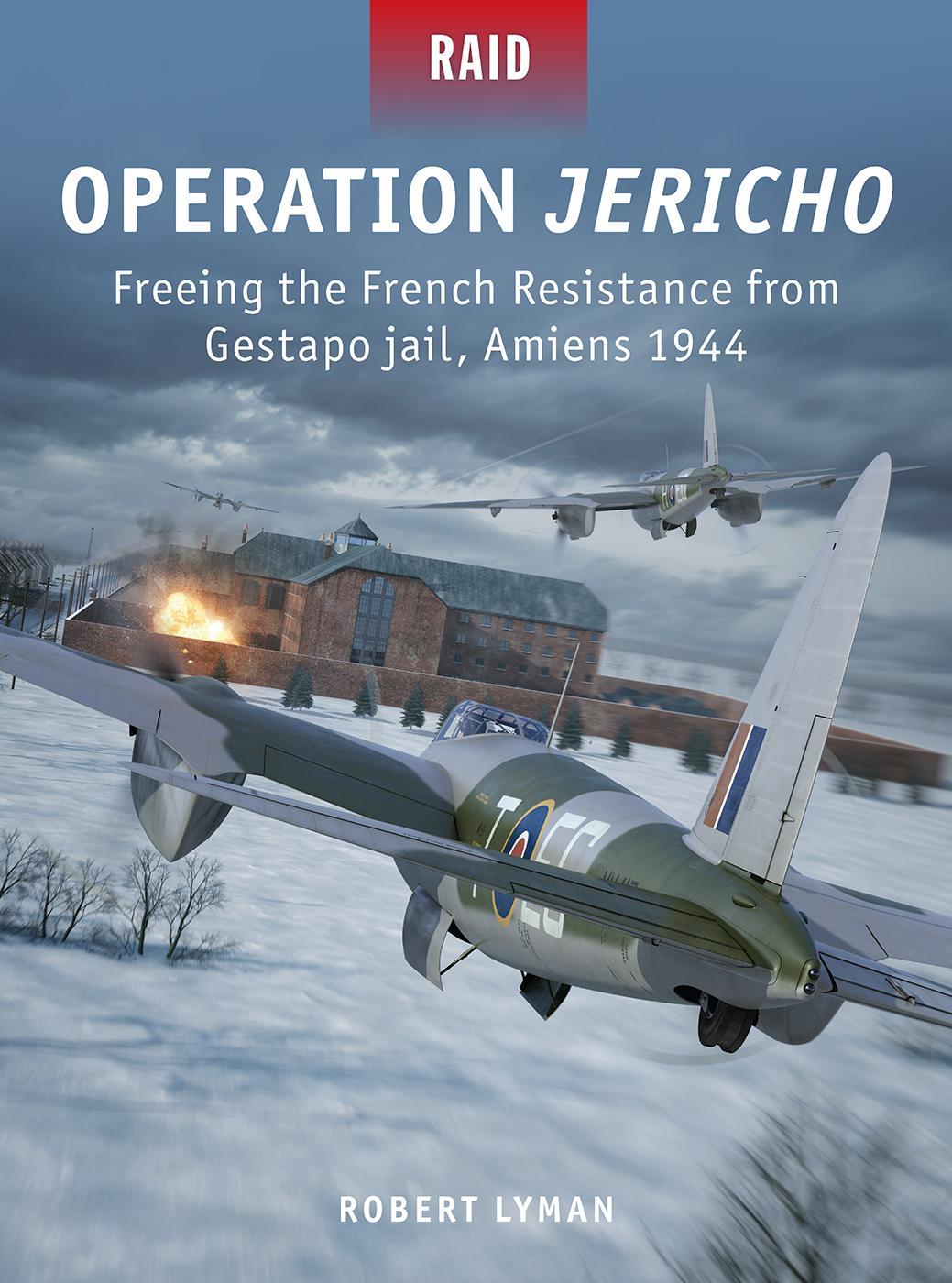

There was a heavy greyness to the morning of Friday 18 February 1944, a typically miserable English winters day. Well after dawn the sky was still dark, due partly to the intensity of the snow swirling thickly over the airfield at RAF Hunsdon in Hertfordshire, 26 miles north-east of London, and partly to the low cloud. Widespread snow over most of southern England that morning and for the past two days had limited all but the most essential flying, and the aerodrome was blanketed with snow.

The poor weather had been a problem for days. Few Allied aircraft got into the air at all. On Thursday, an operation planned for the Mosquito-equipped No. 140 Wing at RAF Hunsdon had been cancelled. Bomber Command had not flown a mass raid for two days. On the night of 15 February a total of 891 aircraft had bombed Berlin, and on the following night 823 aircraft had attacked Leipzig. On this night also 16 February the records list 48 aircraft undertaking operations in support of the French Resistance. But for all of 17 February, Bomber Command had sat idle, freezing temperatures and swirling snow offering the Germans a brief respite from the otherwise relentless terror from the skies. Likewise, for the 2nd Tactical Air Force (TAF) (part, with the Ninth US Air Force, of the newly formed Allied Expeditionary Air Force), Fighter Command and Coastal Command, operations were severely curtailed. Indeed, the original plan had been to launch this raid the day before Thursday 17 February but the harshness of the weather forbade it, and a delay of 24 hours had been imposed.

On waking to their customary cup of tepid tea from the messing assistant, the crews who had been chosen for the mission were told to prepare for a briefing at 8am New Zealand Pilot Officer Arthur Dunlop, Max Sparkss navigator in No. 487 Squadron, recalled:

I was awakened at 6 oclock in the morning, and looked outside, where it was very dark and it was snowing and looking extremely unpleasant. I went over to the mess at Hunsdon and after breakfast went in the crew bus down to the aerodrome which was about a mile and a half away. We had to go there for a briefing at 8 oclock in the morning and I went to get my flying gear and then went into the briefing room.

A crew member of a No. 487 Squadron Mark VI Mosquito, probably at RAF Hunsdon in late 1943, climbing into the cockpit using the side ladder through the fuselage door. (The Air Force Museum of New Zealand)

Armed RAF policemen stood at the door, admitting only those whose identity documents tallied with the list they consulted. This wasnt unusual. Indeed, for some months now the crews of 2nd TAF had been undertaking raids against V1 launch sites across northern France, about which new and strict secrecy procedures had been enforced. RAF policemen had begun to guard the briefing rooms at airfields as a means of impressing upon the crews the sensitivity of their targets, to ensure that they did not blab about them if captured.

In addition to the Commander No. 2 Group, Air Vice-Marshal Basil Embry, two officers from No. 2 Group were present, Squadron Leader Ted Sismore, DFC (No. 2 Group operational planner) and Wing Commander Pat Shallard, the Group Intelligence Officer, together with the No. 140 Wing commander, Group Captain Pick Pickard. A few select individuals had already been briefed on the target, including the commanding officers of the three squadrons of Pickards No. 140 Wing: Wing Commanders Irving Black Smith (No. 487 Squadron RNZAF), Robert Wilson Bob Iredale (No. 464 Squadron, RAAF) and Ivor Daddy Dale (No. 21 Squadron, RAF), together with Flight Lieutenant Antony Tony Wickham of the RAFs Film Production Unit (FPU).

Wing Commander Ivor Daddy Dale, DFC, RAFVR (pilot) (right), commander of No. 21 Squadron RAF, part of No. 140 Wing along with No. 464 Squadron RAAF and No. 487 Squadron RNZAF. Dale was 39 at the time of the raid, a pre-war flyer who returned to service in the RAF Volunteer Reserve on the outbreak of war and was thus much older than the men under his command. He was killed in early 1945 when his Mosquito suffered engine failure over the Netherlands. (IWM HU 081335)

Wing Commander Robert Wilson Bob Iredale, DFC (pilot) and Flight Lieutenant John Mac McCaul, DFC, RCAF (Navigator) No. 464 Squadron RAAF October 1943. Iredale and McCaul were in the second (RAAF) wave of the attack, at 12:06 pm. Both returned safely from the raid. (AWM UK848)

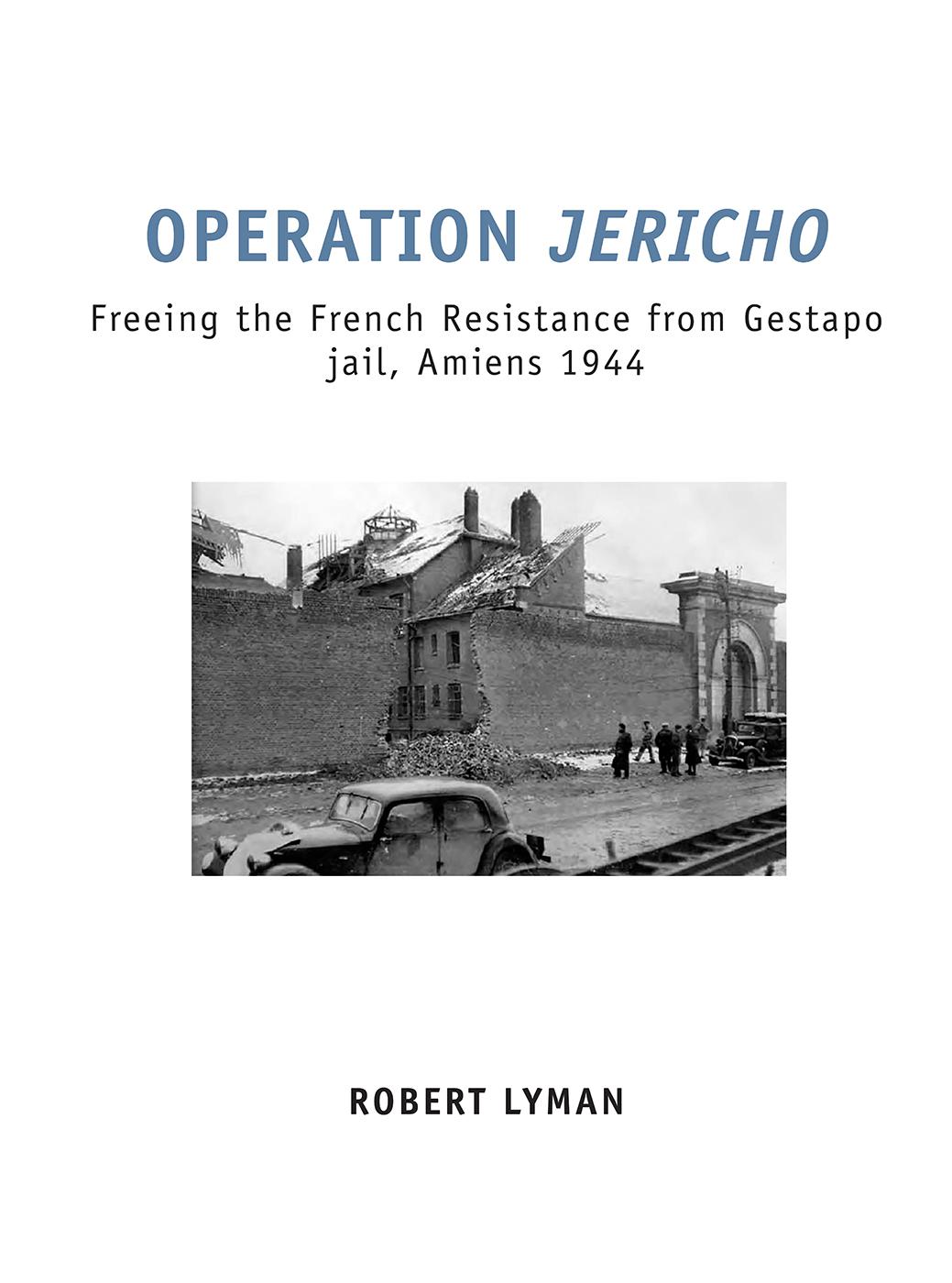

On the briefing table sat a large box, five feet square at the top and six inches deep. When opened, it was revealed to be a particularly detailed plaster of Paris model of Amiens Prison. It had been built following an aerial reconnaissance of the site two months previously, in December 1943, when the Air Ministry had received a request from MI6 to consider an attack to release prisoners from the jail.

The briefing was formal and careful. Pickard and Embry began by revealing the nature of the mission. Pilot Officer Lee Howard of the FPU recalled Pickards briefing:

Your target to-day is a very special one from every point of view. There has been no little debate as to whether this attack should be carried out, and your A.O.C. more or less had to ask for a vote of confidence in his men and his aircraft before we were given the chance of having a crack at it. It could only be successfully carried out by low-level Mosquitos; and weve got to make a big success of it to justify his faith in us, and to prove further, if proof is necessary, just how accurately we can put our bombs down.

The story is this. In the prison at Amiens are one hundred and twenty French patriots who have been condemned to be shot by the Nazis for assisting the allies. Some have been condemned for assisting Allied airmen to escape after being brought down in France. Their end is a matter of a day or two. Only a successful operation by the RAF to break down their prison walls can save them, and were going to have a crack at it to-day. Were going to bust that prison open. If we make a good job of it and give the lads inside a chance to get out, the French underground people will be standing by to take over from there. There are eighteen of you detailed for this trip. In addition, the Film Units special aircraft is coming along to see what sort of a job you make of it. The first six of you are going to breach the walls. Now, these walls have got to be broken down if the men inside are to get out successfully. This will mean some real low-level flying; youve got to be right down on the deck. The walls are only about twenty-five feet high, and if were not damned careful our bombs are going to bounce right over them and land inside the prison and blow everybody to smithereens. We have told the men inside of this risk, through the underground movement, and theyre fully aware of the possibility.