Advance Praise for

Class of 77

The Peking University classmates of Jaime FlorCruz gave him a front-row seat in the tumultous political arena of Chinas post-Mao era. The Class of 77 is unique for FlorCruzs memorable first-hand accounts of knowing some of Chinas movers and shakers in their youth.

Melinda Liu, Newsweek China correspondent

Jaime FlorCruz captures the flavor and drama of his own experience in this fascinating land, the look and feel of countryside and campus, and the whole crazy, compelling sweep of Chinas recent history.

Donald Morrison, former TIME International Editor

Just after setting foot in China, Jaime FlorCruz realized his life was about to change. It was 1971 and the Cultural Revolution was roaring through the land, but Jaime embraced his new homeland and went on to serve as China bureau chief for TIME and CNN. And he was always generous with his information Maos wife killed herself ? Yesterday, Jaime said. Yet another FlorCruz scoop. This memoir tells us how he did it.

Ed Gargan, former New York Times correspondent and author of Chinas Fate

Only Jaime FlorCruz could write this sweeping memoir: a radical student exiled in Maoist China during the Cultural Revolution, his heart broken by not one but two Chinese lasses, eventually heads CNNs Beijing bureau.

Jan Wong, author of Red China Blues

Having served as president of the Foreign Correspondents Club of China, the Beijing bureau chief of TIME magazine and of CNN, Jimi has long been an inspiration to many young China-based foreign correspondents. He has spent more than four decades in China and understands the country inside out, and this book masterfully tells the story of how he came to grips with the dragon.

Benjamin Lim, The Straits Times, Global Affairs Correspondent

The Class of 77

By Jaime A. FlorCruz

ISBN-13: 978-988-8769-49-0

2022 Jaime A. FlorCruz

HISTORY / Asia / China

EB147

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in material form, by any means, whether graphic, electronic, mechanical or other, including photocopying or information storage, in whole or in part. May not be used to prepare other publications without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information contact info@earnshawbooks.com

Published by Earnshaw Books Ltd. (Hong Kong)

To my father Cenon, who encouraged me to seek education wherever the search took me.

To my mother Lourdes, who reluctantly woke me up to catch my flight to China, not knowing we wouldnt see each other again for many years.

To my wife Ana, son Joseph and daughter Michelle, who accompanied me on my remarkable China journey.

To my three granddaughters Jayden, Jazelle and Jolie, children of Janet Correa and Joseph, who inspired me to finish this book so that they may know more about their Lolo Jaime.

Prologue

In 1971, I journeyed into the Peoples Republic of China on what was supposed to be a three-week study tour. I was a student activist in the Philippines and knew little about China. I never imagined it would be another twelve years until I was able to go home again to the Philippines or that I would spend most of my life in Communist China.

I went when Chairman Mao was in power, and the tumultuous Cultural Revolution was still in progress. Over the next fifty years, I had a ring-side seat to the most remarkable economic and social transformation in human history. I watched the rise of China under Deng Xiaoping and his successors from the ashes of the Cultural Revolution, and witnessed its transformation from one of the poorest, most isolated countries in the world to a renascent global power.

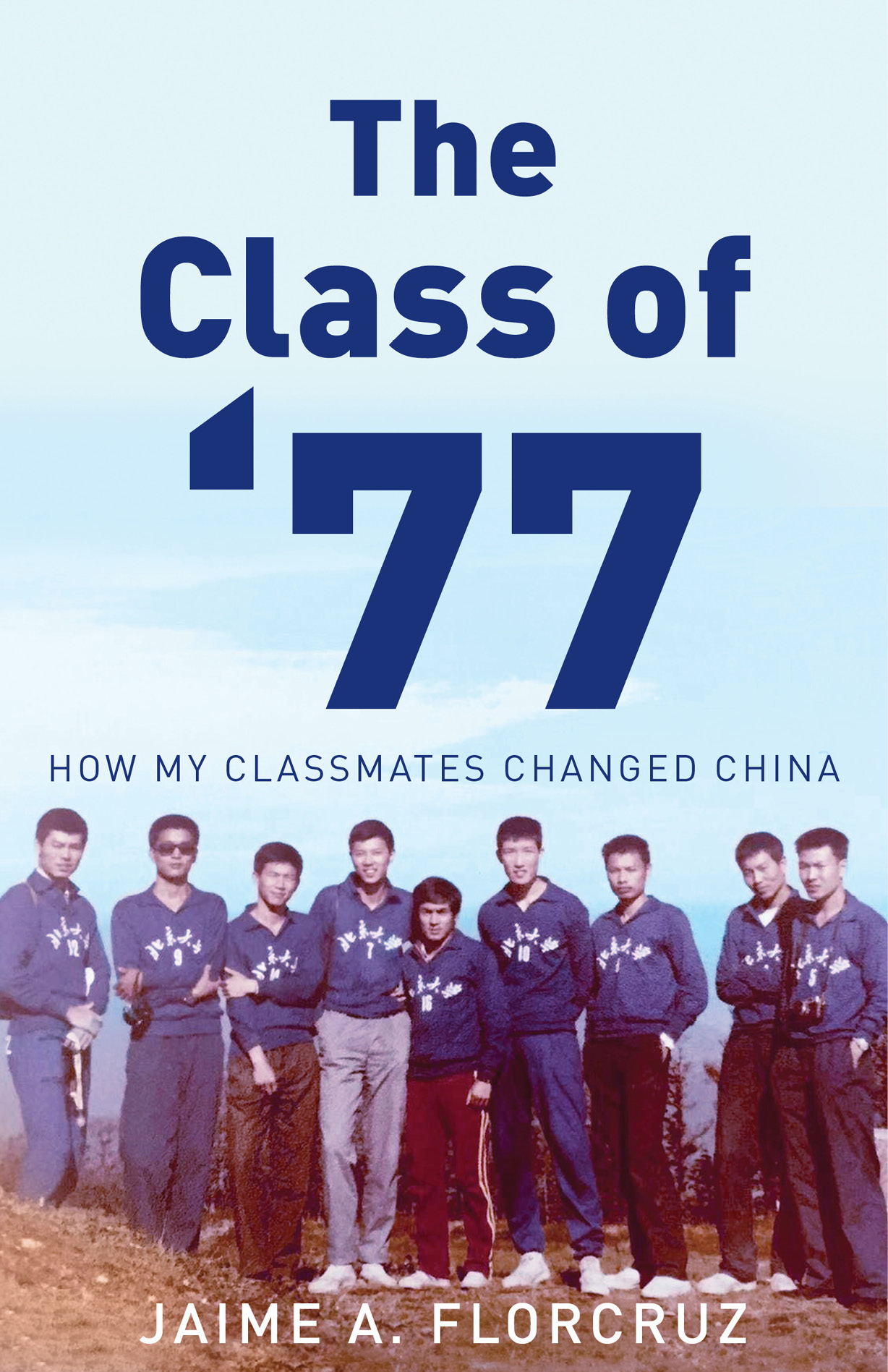

I started my journey as a student and ended as head of TIME Magazine and of CNN in China. But what really transformed my life was being part of Peking Universitys rightfully famous Class of 77.

This is my storyand our story. This is the story of the Class of 77.

Through The Gate

On a sunny , nippy day in October 1977, I walked into the West Gate of Peking University with much anticipation. The palace-style portal, painted in vermillion, evokes the universitys long and storied past. A big plaque hangs in the middle of the gate with the name of the university carved in four Chinese characters, Bei Jing Da XuePeking Universityin the calligraphy of Chairman Mao. I was there to enroll as a freshman in the Class of 1977.

I proceeded to look for the Foreign Students Office, my first stop to register. I crossed a small stone bridge over a moat dotted by lotus plants. Cicadas were chirping, frogs croaking. Yellow leaves blown off by the brisk autumn wind covered the sidewalks of the narrow road. A stone statue of Chairman Mao towered in front of quaint old buildings painted in red and white and topped with pagoda-style roofs. Further down, behind the traditional-style buildings, was the charming Weiming Lake.

Days earlier, I made a special trip to the Youyi (Friendship) Photo Studio, near Tiananmen Square, to get ID photos taken, then proceeded to the Capital Hospital for a medical checkup. I also made photocopies of my diploma and transcripts from the Beijing Languages Institute, where I had recently completed a three-year course in Chinese language and translation. Peking University required all of them for enrollment.

Cai Huosheng, a stocky fifty-something staff officer of the Foreign Students Office, greeted me at the door.

Youre the only student we are enrolling from the Philippines this year, he said, as I handed him the required documents. Welcome. Welcome.

He volunteered to show me around for orientation. We walk past the Library and a classroom building, where scores of students are on a break. Most wore blue and green Mao jackets and baggy pants. They were lined up on the sidewalk doing calisthenics in synch with the staccato music blaring from the universitys PA system. It was the same prescribed group exercise that we used to do in the Beijing Languages Institute. I noted that the students were mostly older, looking to be in their late twenties and early thirties. Some wore PLA military uniforms.

They are the gong-nong-bing students , Teacher Cai explained, referring to the Worker-Peasant-Soldier college students on campus. They may be the last batch of that cohort.

When the Cultural Revolution started in 1966, all universities were closed, and the gaokao , the national college entrance exam started in 1952, was abruptly scuttled. Some schools, like Peking University, reopened in 1970, but only to enrollees recommended by their work unitsthe peoples communes, factories and the militarybased on their work attitude and political correctness. Based on this recommendation system, those who had bad family background need not apply. Tests, deemed elitist, were taboo.

By the summer of 1977, about a year after Maos death, the news came that the gaokao examination for college entry would resume. Because there was little time to prepare for the first nationwide college entrance exam since 1965, the planned tests were moved back to November and December 1977. That meant my Class of 1977 cohorts would not be able to enroll until Spring 1978, after they had passed the gaokao .

Meantime, you may get started by taking up core subjects with the Worker-Peasant-Soldier class, Cai advised.