ALAN WHICKER

WHICKERS WAR and JOURNEY OF A LIFETIME

ALAN WHICKER

WHICKERS WAR

Dedicated to the men of

the Army Film and Photo Unit

who marched with me through Italy

CONTENTS

O ne mans war a return to the invasion beaches and battlefields of Italy. A sentimental pilgrimage, I suppose, to places where I expected to die. Also a salute to those I marched alongside 60 years ago while growing up watching the world explode before the viewfinders of Army Film Unit battle-cameramen. In two years of savage warfare they gave a lot; some of them, everything.

As a teenage subaltern Id volunteered for a new role in a new Army, and found myself out of the infantry but in to far more assault landings and battles than Id expected. My belief that war could be anything except boring went unchallenged because our cameramen closely followed the action, indeed sometimes led Italian though that was usually just poor map-reading

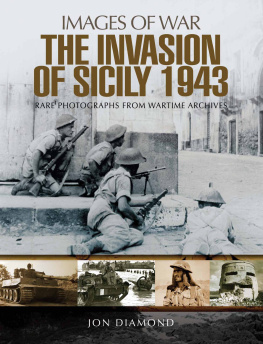

I was part of the first great seaborne invasion. The Eighth Army was learning how to do it and so, unfortunately, were the Germans.

The Italian campaign one of the most desperate and bloody of World War II was 660 days of fear and exhilaration. Churchill called it the Third Front. Life was strangely intense and sharp-focussed, yet every dramatic experience vanished like an exploding shell as we moved cheerfully along the cutting edge of war towards the next violent day.

The defence of Italy cost the Axis 556,000 casualties. The Allies lost 312,000 killed and wounded and remember, this was The Overshadowed War. After Rome the Second Front captured our headlines and at Westminster, Lady Astor won the Hollow Laugh Award by calling us the D-Day Dodgers.

As in the Great War, we subalterns had short sharp life expectations. Like those 19-year-old Battle of Britain pilots we learned to cope with this dismal forecast by being flip and jokey, but alert. It seemed to work for me though more than half our camera crews were killed or damaged in some way while earning their Medals and Mentions.

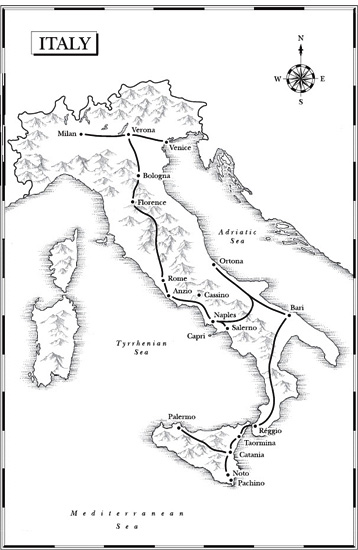

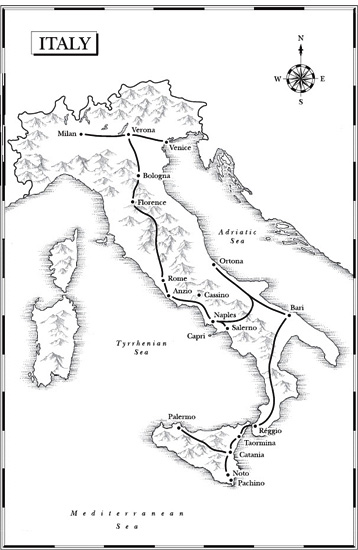

As part of a massive Allied war fleet we joined this first great invasion of 2,700 ships and landing craft and on July 10 43 struggled ashore on to Pachino beach at the bottom right-hand corner of Mussolinis island, expecting the worst. Around me on that early summer dawn in Sicily, 80,000 Eighth Army troops were also landing, and looking for a fight.

Our cameramen embedded in frontline units faced bitter warfare that I suspect few of todays young soldiers let alone young civilians could envisage in their worst nightmares. Among the perils in our path lay Churchills gamble that failed, doomed by uncertain planning and leadership: the Anzio Bridgehead, where we all ceased to be young, where 250,000 soldiers were locked into a series of battles unique in the history of World War II. There in a few weeks of savage siege warfare 43,000 of us would be blown into history: 7,000 dead, 36,000 wounded or missing-in-action but as we fought through Sicily such horrors lay ahead, unsuspected.

I stayed with Montgomerys desert army as it crossed the Straits of Messina to attack the Italian mainland. Then after Salerno went with the British/US Fifth Army to land 80 miles behind German lines, at Anzio. Our orders were to outflank Monte Cassino, cut Kesselrings supply lines, destroy his Tenth and Fourteenth armies and liberate Rome. Thats all in the afternoon wed go to the cinema

Breaking out of the bridgehead after 18 desperate weeks, the Fifth Army finally liberated Rome, though our war was lengthened by almost a year and many lives lost by the vanity of one insubordinate Allied General.

The Eighth fought on through the Apennines and the Gothic Line before sweeping down into the Po Valley to reach the Alps and victory. Italys Dictator Benito Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci were then hunted down and killed by their communist countrymen.

Those who doubted the strategic significance of our role in tying down 25 German divisions in Italy for two years and the 55 divisions deployed around the Mediterranean would have been heartened by Adolf Hitlers reaction. As we invaded Sicily and so pinned down one-fifth of Germanys military strength, he was controlling his wars from the Wolfschanze, his headquarters in East Prussia. He told his Generals that Citadel, the planned offensive against the Russians at Kursk, would be called off immediately. Their troops would go instead to the Italian front. That decision certainly did not make our task any lighter, but helping the Red Army was in fact our first victory before firing a shot.

When we waded ashore on Sicily there were 2 German divisions in Italy. Next year, as the Second Front opened, there were 24 with three more on the way. We had made a difference. Even I made a small difference to the German SS by capturing several hundred of them, plus their General; I was also given a hidden fortune of many millions in hard currency and then went to live in Venice. As Churchill said of our broader Mediterranean canvas: there have been few campaigns with a finer culmination!

Sixty years later I returned to Pachino to watch the sun rise over beaches where I had waded ashore up to the waist in warm Mediterranean and taken my first soggy steps on the long slog towards the Alps. I was then approaching two years of the worst and a few of the very best experiences of my life, when just staying alive was a celebration.

T his Odyssey began before the war with a Certificate A from the Officers Training Corps at Haberdashers Askes School, Hampstead where, alarmed by the growing shadow of Hitler, we played at soldiering one night a week, went to summer camps and struggled with our exasperating puttees.

Came the war and I enlisted and was brushed by glory and instant power when made a Local Acting Unpaid Lance Corporal. Sewing on the lone stripe was a significant moment, rather like the ecstatic sight of that first bicycle. (I can still see mine leaning against the garden fence, all chrome and gleam. Compared with such utter bliss the sight of my first Bentley was as of dust).

I joined-up at the vast Ordnance Depot of Chilwell, outside Nottingham, and was selected as possible infantry officer material, which was worrying enough. The war had not been going well for us, and a moments reflection would have warned me that if I wanted a long and happy life, the infantry was not the way to go.

In pursuit of that hazardous promotion, I drove north with my friend Harry Hamilton. He had a Ford Anglia and a hoarded petrol ration. Along almost deserted wartime roads we headed for Carlisle Castle and a Border Regiment training course which would find out whether we were the right kind of cannon fodder. With a hundred potential officers we shivered through an icy January in two vast Crimean barrack rooms, sleeping on iron bedsteads and queuing to unfreeze a couple of taps. The wind whistled against cracked windows in a scene Florence Nightingale could have drifted through, the Lady with the Lamp looking concerned about her poor boys.