Copyright 1995 by the University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eastman, Yvette Szekely

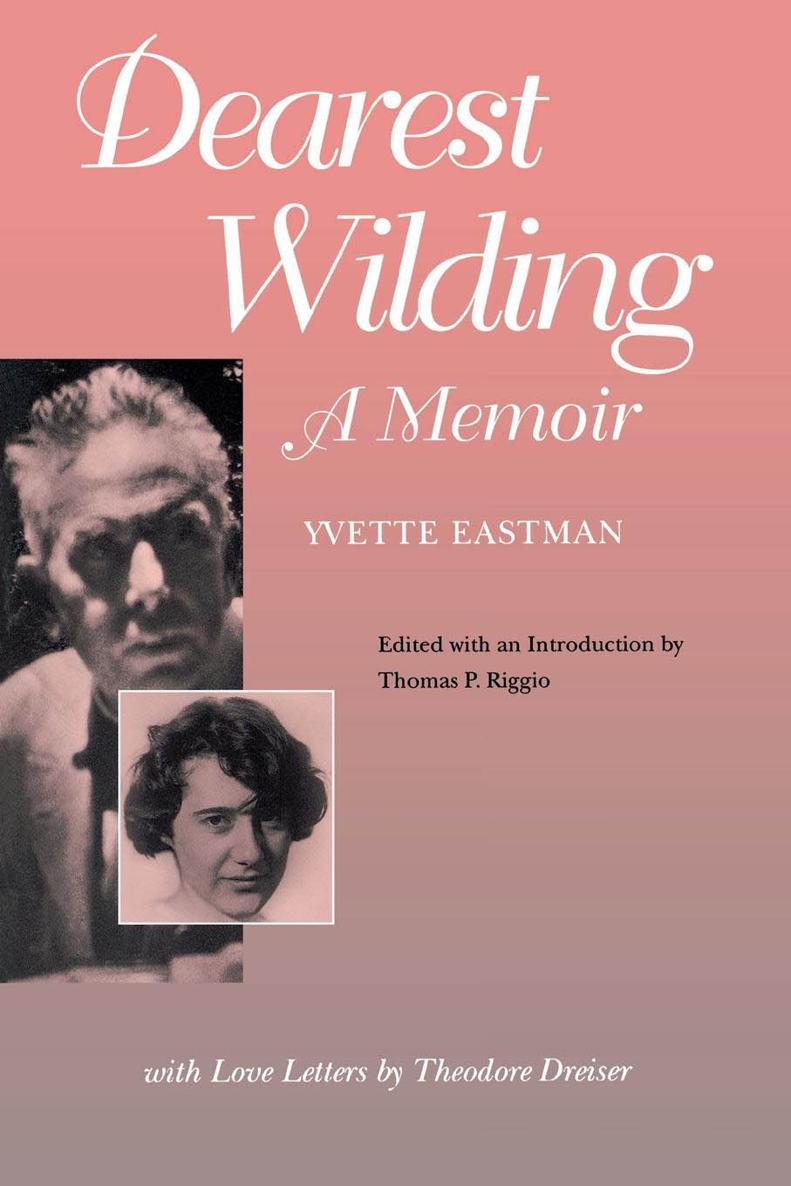

Dearest Wilding : a memoir : with love letters from Theodore Dreiser / by Yvette Eastman ; edited, with an introduction and annotations, by Thomas P. Riggio.

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-0-8122-1646-2

1. Dreiser, Theodore, 1871-1945Relations with women. 2. Dreiser, Theodore, 1871-1945Correspondence. 3. Eastman, Yvette SzekelyRelations with men. 4. Novelists, American20th centuryBiography. 5. Love-letters. I. Dreiser, Theodore, 1871-1945. II. Riggio, Thomas P. III. Title.

PS3507. R55Z62 1995

813' . 52dc20

CIP

Designed by Carl Gross

Yvette Szekely Eastmans memoir is the latest, and arguably the most revealing, of a number of books written by women who knew Theodore Dreiser. Biographers eventually will have to explain why Dreiser, for all his unsavory reputation as a careless philanderer, has inspired more such reminiscences than any other American writer. Helen Dreiser, Margaret Tjader Harris, Dorothy Dudley, Ruth Kennell, Clara Jaeger, Louise Campbell, and Vera Dreiser have all added to the record of the novelists life. Dearest Wildingthe title comes from a term of affection Dreiser used to address the authorsurely provides the most intimate account. This is attributable to Mrs. Eastmans considerable narrative skills, to her eye and memory for vivid details, and to the quality she says she most admired in Dreiserthe detached, nonjudgmental yet compassionate acceptance of what life brings.

Dearest Wilding records the journey that took eight-year-old Yvette Szekely from an upper-middle-class scholars home in Budapest to the intellectual and artistic centers of urban America in the 1920s and 1930s. The key moment of Mrs. Eastmans memoir is her fateful meeting with Dreiser in 1929. She was then a sixteen-year-old schoolgirl and he a famous friend of her mother. Although the narrative ends with Dreisers death in 1945, this is more than an account of their sixteen-year relationship. Mrs. Eastmans attempt to understand the nature of her bond with Dreiser forced her back even further, to her early childhood in Hungary, to memories of her erudite and famed but distant father who did not accompany her to America, and to the formative experiences and subsequent psychic hungers that made the aging writer so important a part of her life.

Mrs. Eastmans youth, tied as it was to Dreiser and his circle, provided her with a privileged view of a special phase of modern life. Her distinction comes in part from the circumstances that placed her, from an early age, among the most noted figures in twentieth-century cultural history. In retrospect, she was fortunate to come to the United States with a motherthe Margaret of the storywho had, as Mrs. Eastman says, a way of being where the action was, more especially if the situation held people of fame and importance or a cause she could support.

The causes of the period were many, from progressive political action to now obscure struggles for literary freedom. Beginning in 1929, Dreiser, then fifty-eight years old and at the height of his fame as a writer, invited Margaret Monahan and her two daughters to the popular Thursday evening soirees at his Rodin Studios apartment on West 57th Street and later to his country home, called Iroki, at Mount Kisco, New York. By this point Dreiser had put behind him the relatively impecunious lifestyle of his Greenwich Village days and had moved uptown to the posh apartment where, in his own inimitable way, he participated in the whirlwind pace of the late 1920s. A typical evening might find young Yvette in the same room with such writers and critics as Sherwood Anderson, John Cowper Powys, Floyd Dell, Edgar Lee Masters, and Claude Bowers; the banker-producer Otto Kahn; Freuds American translator, A. A. Brill; the actress Miriam Hopkins; the columnist Alexander Woollcott; and the multifaceted intellectual Max Eastman, whom she would later marry. Naturally, there was something intoxicating in this company for one so young. At first shy, she soon became a familiar presence among the artists and authors who had made New York their mecca in the nineteen-teens and twenties. Mrs. Eastmans portrait of Dreiser and his set is of course a valuable primary source in literary history. I might add that it is likely to be among our last such documents from this period.

In the thirties Dreiser addressed himself to the social and political challenges of the decade, and he became deeply involved in compiling a massive philosophical-scientific study on the nature of existence. Mrs. Eastmans memoir offers a view of the less public side of his life that has largely eluded biographical accounts. It presents an evocative and colorful picture of those times rendered with a fine eye for the texture of everyday life. Mrs. Eastman captures especially well the poetry and tensions of the teenager in all her navet and youthful adventuring, in love with love, with poetry, and with the lover-father in this celebrated man. It is a very human document about a young woman enthralled by the celebrity and magnetism of a writer who was sixteen years older than her father. Her portrait of Dreiser, not by any means idealized, is of a complex man who was often troubled, suspicious, unfaithful, and jealous but who also cared and was supportive and not just for selfish ends.

Dearest Wilding is the first installment of a full-fledged autobiography, which culminates in Yvette Szekelys marriage to Max Eastman in 1958 and their years together until his death in 1969. That story employs a large canvas and includes detailed portraits of many public figures of the postwar years. Dearest Wilding has a design of its own, resembling a traditional bildungsroman, which follows the course of a life back to certain primal encounters. For Mrs. Eastman, the entire scheme of her life was radically altered by her experience with Dreiser. Their relationship, which began as a strange, even clumsy seduction, finally became, as Mrs. Eastman presents it, more like the supportive friendship that might exist between a father and daughter. She describes it best in a passage from her larger work:

[Dearest Wilding] is a memoir of growing up and declaring independence, using my relationship with Dreiser as a centerpiece, walking with stubborn, unseeing innocence, straight into buffeting headwinds. It is primarily about a young me, how I saw TD and his impact on me, his effect on my life. It is also about my relationship with my mother. She and TD stand out as centers of influence and conflicta sort of triangle with TD pulling me away from my mother and toward a wider world, and in the background my father for whom TD was somewhat of a substitute.

Mrs. Eastmans decision to allow Dreisers letters to accompany her story makes the memoir more personal and more valuable as a historical record. This book is something of a publishing event, as it includes the first collection of Dreisers love letters. Although researchers have had access to such letters among the Dreiser papers at the University of Pennsylvania, they have rarely quoted from them, even in biographical accounts. Until now the letters in this book have been unavailable to specialists as well as to the general public. (Unfortunately, only a handful of Mrs. Eastmans letters to Dreiser have survived, and these appear in the memoir itself.) Readers will discover that Dreiser never wrote mere love letters. He often included reflections on his surroundings, on life, politics, his writing, and the famous and the unknown whom he encountered. The letters also reflect the heady last days of the twenties, the reform-minded thirties, the toll the war took on the German-American novelist during the late thirties and early forties, and the concerns of his last years. They are, of course, primarily a mirror to Dreisers various moodsthe wistfulness, joy, loneliness, and tenderness that often warred with the less appealing qualities. In this they supplement Mrs. Eastmans account as only such private papers can.