This ebook edition published in 2011 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 1983 by Bidean Books, by Beauly

Republished in 2001 by Birlinn Ltd

Copyright Iain R Thomson 1983, 2001 and 2007

The moral right of Roger Hutchinson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ebook ISBN: 978-0-85790-044-9

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Isolation Shepherd

The hills wide symphony of silence

Sweeps down by a far lost way;

Music of isolation and peace

Carries time to horizons rim

Where the wistful plovers call

Plaintive clear, on a distant day,

Reaching harmonys only source

In the spirit of a single mind.

But gone is the ear that hears it,

Lost is the breath of care;

Scattered the race to dreaming

Fond eye to Corrie and Beinn.

Heavy the loss that is Highland

For the hills of striding men.

Shelter the glens that are weeping

In the care of a single hand.

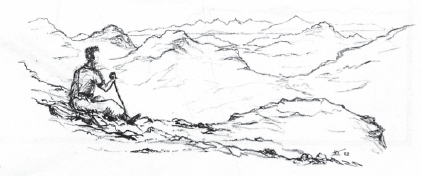

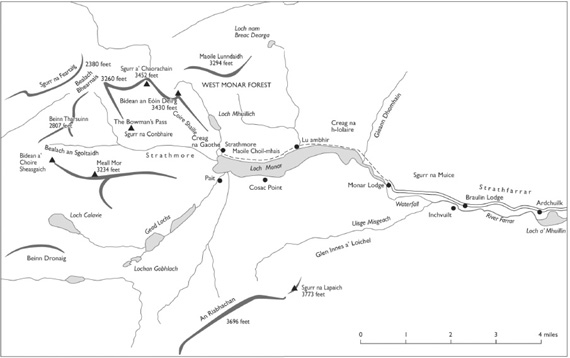

BY STORM TO STRATHMORE

A southwesterly gale and heavy showers swept down Loch Monar. It had been blowing and raining since the previous day. Though summer storms are not infrequent in the high hill country of the Highlands, this one was severe. The Spray, a clinker-built 26-foot ex-ships lifeboat was to demonstrate her qualities in dealing with rough conditions as we left the shelter of the narrows at the east end of the loch. Head on she met the full force of the weather in the wider open waters. Her cargo that particular day, 13 August 1956, was my family, flitting, destined for a new home six and a half miles of stormy loch westwards from Monar. Here, cradled in remoteness and grandeur at the upper reaches of Glen Strathfarrar, lay Strathmore.

We were quickly to learn that the wave action on large fresh water lochs is quite unlike that of the sea. Wave follows wave in quick succession, deep troughs and sharp breaking tops make dangerous conditions especially as a boat lacks the buoyancy it would have in salt water.

Iain MacKay leaned over the tiller. The Spray drove into a press of surging water. Shielding my eyes I stared ahead. White rolling tops stretched to the grey indistinction of storm-swept hills. Astern, the long streaked wave backs heaved powerfully away from us. Capricious gusts, sometimes snatching the crumbling crests, threw spiralling sheets of water to meet the rain. Our world shrank to simple elements: raging and shrieking, warning or welcome. Gone the false world of human progress; I felt the first thrill of wild isolation.

Handling the heavily loaded launch required skill. Occasionally bursting through the crest of a viciously curling wave she would crash into the following trough with a solid thud which shuddered the whole length other timbers. Arched sheets of water shot into the air to be caught and hurled across the huddle of us crouched at the stern.

Sometimes a broader wave would lift the stern until the propeller almost cleared the water allowing the four-cylinder engine to rev and clatter alarmingly. Rising to the next wave, the propeller dug deep, biting much water. The engine dropped to a sickening struggle. With a hint of unspoken concern Iain would give her more throttle. Should the engine stall in such heavy conditions and the Spray turn broadside, well, we preferred not to think.

Violent gusts bore down on us, whipping rain and spume into our screwed eyes. The two MacKay brothers and myself were bent oilskinned figures in the exposed engine cockpit. Green tarpaulins running with water covered our worldly belongings in the centre well of the boat. Across them I glanced at the family. They sat apprehensively under the open-fronted hood which served as a cabin two-thirds of the way forward. I had visited Monar some weeks previously when first engaged as shepherd but this was my familys initiation to a wind-tossed lonely world and perhaps the more fearsome for Betty as she was unable to swim. To my relief I saw that under a shawl she was quietly feeding Hector our ten day old baby. Alison, his two-year-old sister sat close to her mother, wide-eyed but silent.

The passage west to Strathmore, due to the conditions that day, took about an hour and a half whereas a trip up the loch in fair weather could be done by the Spray in forty minutes. Little was to be seen of the majestic hills, only fleeting glimpses of black and green betokened their massive presence as mist and cloud, swirling low before the westerly blast, clawed across their aristocratic faces.

The loch was in high flood. This added power to the waves as we surged westwards towards a line of breakers stretching across the head of these open waters. I could see the reason for these rough conditions was a sandbank, a natural formation which reached out from the south side of the loch in a sweeping curve to within forty yards of the north shore. A spit of sparkling mica sand, it generally showed well clear of the water level. On normal days a feat of navigation was required to negotiate this narrow channel, or the corran as we called it. A dog-legged swing past an iron standard marker veered ones boat hard towards the north bank before a smart turn avoided apparent disaster and the tricky passage afforded access to the head of the loch.

Young Kenny MacKay took the handkerchief from about his throat, Well not be needing to use the corran today, he said, wiping his face. The level must be eight feet up and the half of it feels down my neck.

Trusting their judgement, the boys stood the boat into the heavy breakers. A moment hung tense. Would we strike? Twenty yards, spray and violent motion; I saw the boys relax, we were across the shallows.

Astern of us I spotted the Monar launch making up at speed. She sliced into the waves throwing water aside in fine clipper style. A fast, sound boat, again clinker built, but lacking the beam of the Spray she was not so suitable for cargo. Allan Fleming the Monar keeper, Mr. Roderick Stirling my new employer and Big Bob Cameron the ghillie were aboard her. Their deerstalker bonnets bobbed above the cabin roof as they too judged the depth of the sandbank before sailing over it.

![Iain Maitland [Iain Maitland] - Mr Todd’s Reckoning](/uploads/posts/book/141709/thumbs/iain-maitland-iain-maitland-mr-todd-s.jpg)