Kamala Magar, heart racing, stomach rising, gathered herself by focusing on the little things her lawyers had told her to do. Sit tall and straight in your chair. Interlace your fingers and place your hands on the table in front of you. Breathe.

The long tables dark finish was so glossy she could see her hands and face reflected back in a kind of shimmer, as if she were looking into a still pool. A packet on the table marked Exhibit 58 held her memories in photocopied snapshots: her husband posing alone in front of their farmhouse; her ten-year-old daughter beneath the endless blue of the Himalayan sky. Directly across the table from Kamala, a video camera fixed on a tripod stared her down. On either side of it sat defense lawyers, each representing one of the two companies she was blaming for her husbands death of almost a decade earlier, when she was not yet nineteen. The lens closed in on her face. Her breathing quickened.

She wore a royal-blue long-sleeve kurti top with embroidered lilac trim swirling across her chest. The shawl around her neck was tightly wrapped, more like a piece of armor than a scarf, but the weight of a lapel microphone pulled it low, exposing her throat to the chill of the conference room. Terrilyn Crowley, the court reporter, sat off to the side with her stenography machine. Crowley had come to Washington, DC, all the way from Houston for the deposition, chosen by the attorney seated to the left of the camera. He represented KBR Inc., formerly known as Kellogg Brown and Root, the $4.5 billion military and construction contractor that had generated so much controversy during the Iraq War for its Texas-based parent company, Halliburton. The conference room was home turf for KBR, even though it was far from Texas. They were in the heart of Washingtons K Street neighborhood, on the top floor of a glass-sided building, where KBRs law firm resided. K Streets boulevards are canyons lined with office blocks, each building nearly equal in height and brimming with lawyers and lobbyists representing Americas biggest companies.

Crowley administered an oath to Kamala. She swore to tell the truth.

Joseph Sarless boyish face masked the sharpness of his cross-examination skills. His tone with Kamala as he began his interrogation lacked sting, but it also held no warmth. Filming a deposition tends to affect the conduct of lawyers and witnesses alike. If for some reason Kamala could not appear at trial, jurors might see this as her only testimony, hence her hands folded on the table, her back against the chair, her composed presentation. Sarles, too, needed to be careful, not just about what he said to the widow, but also about how he said it. Jurors might sympathize with Kamala even more if his questions came off as cruel or aggressive toward a young woman who had been through so much.

Sarles kept his voice at a steady, bloodless pitch, as if reading aloud from an accounting textbook. His tone barely changed when he began asking Kamala about four of the worst minutes of her life.

Did you ever see any video, at any time, that related to your husband? Sarles asked.

Kamala drew a deep breath and slumped forward. Tears welled behind her eyes, but she sat still, staring, lost, into the tables reflection for what seemed an eternityfive seconds of silence passed, and then ten, and then twenty. No one in the room made a sound. Kamala swiveled gently from side to side in the gray chair, as she did when she comforted her daughter, eyes still lost in the tables sheen. Slowly, she lifted her head. Yes, she said, looking back at Sarles. I have.

Can you describe what video youve seen? he asked.

Kamala dropped her gaze to the table again. This time it took only a few seconds for her to gather herself and look back toward her questioner. I saw the onethe one in which they killed him, she said, almost in a whisper.

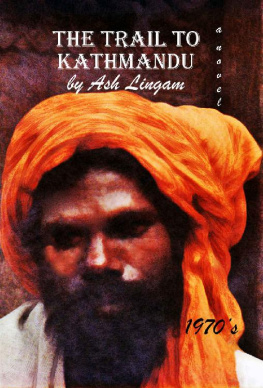

Virtually everyone in Kamalas life, nearly everyone she had ever met, nearly everyone in her homeland, had watched her husband die. Vendors had sold the execution video on DVD in the dusty streets of Kathmandu and even in the smaller towns. Some had hawked single viewings in curtained booths offered with a cup of tea for just a few pennies. Even the other widows in the ashram where she had lived after being rejected by her late husbands family knew how he had died, or had even viewed his murder. When she met people for the first time, she felt their knowing pass as a momentary silence, or saw it in an arrested expression on their faces once they realized who she was. After Kamala learned she might testify, she had yielded to a voice that told her she had to see, had to know, despite all her instincts in the almost nine years in which she had avoided those four minutes and five seconds.

When did you see it? Sarles asked her.

After a long time, Kamala said.

Who showed it to you?

I looked at it myself. I watched it on my own, she said.

Where were you when you watched it?... Were you at your house, or were you someplace else?

At my house, Kamala said.

How did you get a copy of the video?

Objection! said Anthony DiCaprio, seated directly to Kamalas right. There was no judge in the room to rule on DiCaprios objection, but objections in depositions are common, creating markers in the record that allow questions to be challenged and stricken later if warranted. They also give lawyers a tactical tool to emphasize a line of questioning that could be seen as unbecoming to jurors watching later on a big screen in the courtroom. Kamalas lead attorney, a decorated human rights lawyer named Agnieszka Fryszman, had brought DiCaprio into the case specifically for this purpose. Youll be our pit bull, she had told him.

Fryszman looked drawn. The lids of her brown eyes drooped and shed lost so much weight that her lucky outfit, a black pantsuit shed worn for years to every court appearance, gave her the look of a child dressed in her mothers clothes. There didnt seem to be a limit to the resources KBR was piling into its defense. Its cadre of lawyers fought even some of the most mundane facets of the litigation to the extreme, burying Fryszman in so many paper salvos that she didnt have time to depose a single KBR employee, even as a trial date loomed on the court calendar. The defense had also made the fight personal, accusing Fryszman of misconduct in a raft of charges that might derail her career and hurt almost every lawyer who had helped her in the case. Her assistant counsel, an idealistic young woman with degrees from Harvard and Columbia, had resigned after skirting the edge of a nervous breakdown. Now, as Kamala suffered through her interrogation, Fryszman and her law firm had just one week left to respond to KBRs charges. A star witness had stumbled badly in an earlier deposition, giving KBR more fodder. If Kamala broke down under questioning, the defense could pounce again, dealing a potentially significant blow to the case at the worst possible moment.

![Kyle Simpson [Kyle Simpson] - You Don’t Know JS: Up & Going](/uploads/posts/book/121420/thumbs/kyle-simpson-kyle-simpson-you-don-t-know-js.jpg)