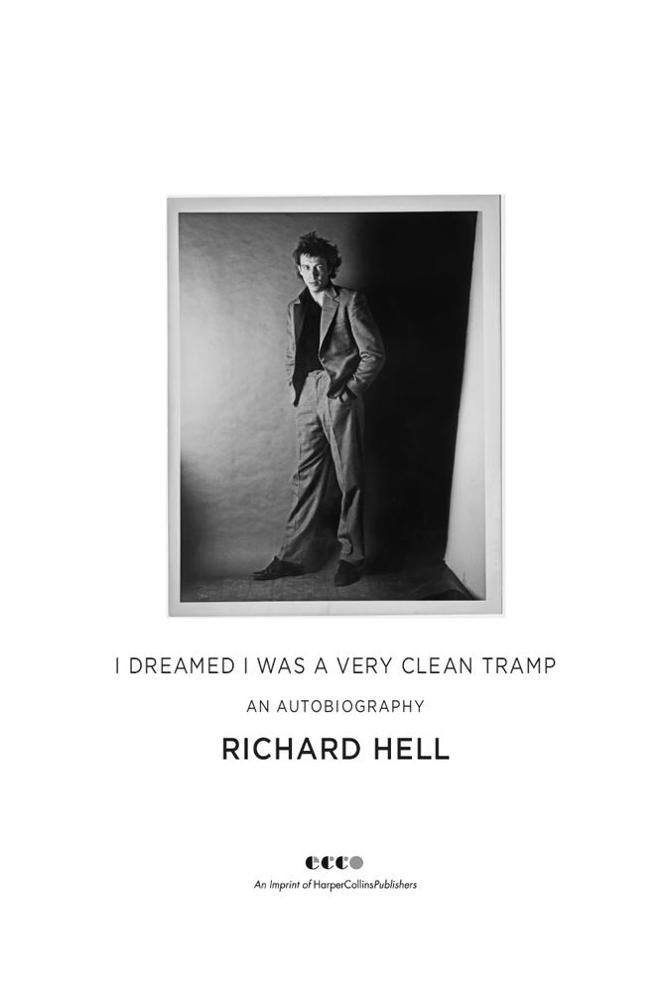

To Sheelagh and Ruby

Contents

L ike many in my time, when I was little I was a cowboy. I had chaps and a white straw cowboy hat and I tied my holsters to my thighs with rawhide. Id step out onto the porch and all could see a cowboy had arrived.

This was in Lexington, Kentucky, when everybody was a kid. I looked for caves and birds and I ran away from home. My favorite thing to do was run away. The words lets run away still sound magic to me.

My parents arrived in Lexington in 1948. Theyd met two years before at Columbia University in New York, where they were graduate students in psychology, and had married a year after that. When my father, Ernest Meyers, whod grown up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, got his Columbia PhD, he found a job teaching at the University of Kentucky. I was born in late 1949. My ma postponed a career to take care of the home.

Our family was just the four of us, including my sister, Babette, who was born a year and a half after me. We felt close to my fathers mother, Grandma Linda, who lived in New York, and we occasionally visited one of his brothers, Richarda chemist for Texacoand his wife and kids, at their home near Poughkeepsie, but beyond that there wasnt much awareness of family, or family history. I had no real understanding of what a Jew was, for instance, though I knew that my fathers family fit that description somehow. I thought Judaism was a religion, and we didnt have any religion.

My mother, born Carolyn Hodgson, was an only child. Her mother, Dolly Carroll (born Dolly Griffin), whom we knew as Mama Doll, was a working-class Methodist lady from Alabama. She played bridge and liked a cocktail. Shed been married four times. We saw her for a few days once every three or four years. She and my moms father, Lester Hodgson, whod owned a filling station in Birmingham until it went bust in the Depression, had divorced when my mother was a young child, and I only remember being in the same room with him two or three times.

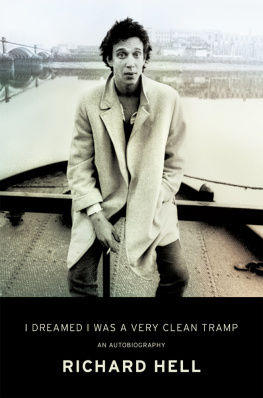

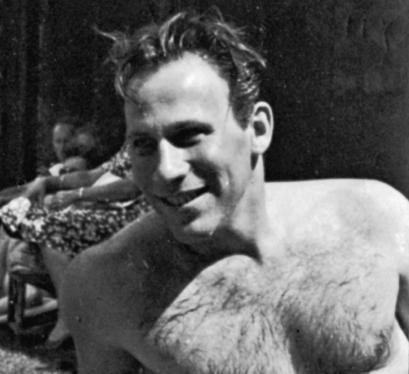

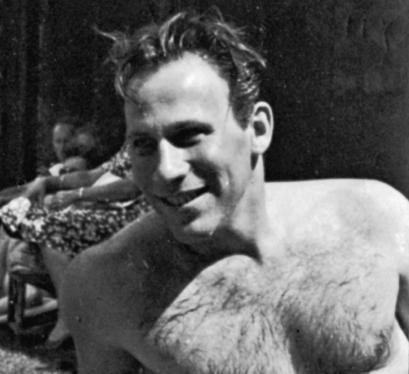

Ernest Meyers, 1948.

We lived in the suburbs in America in the fifties. My roots are shallow. Im a little jealous of people with strong ethnic and cultural roots. Lucky Martin Scorsese or Art Spiegelman or Dave Chappelle. I came from Hopalong Cassidy and Bugs Bunny and first grade at ordinary Maxwell Elementary.

I came from Hopalong Cassidy

In 1956, when I was six and we lived on Rose Street by the university, my father bought a cream and green 1953 Kaiser, which he drove to work every morning a mile down a street that ran between the big UK basketball arena and its football stadium. His campus workrooms were in an old tree-shaded red-brick building on the side of a hill. The classrooms, lab, and office there smelled of wood, chalk, wax, graphite, dust, fresh air, and armpits. The rooms were softly shadowed wood. Tree limbs swayed outside the windows. My father was an experimental psychologist; he didnt treat patients but observed animal behavior in labs. Small hard-rubber rat mazes lay on the tabletops among big manual typewriters. There were wooden glass-front cabinets against the walls, and rows of chair-desks facing the blackboards. That type of plain old academic building, or the one that housed the local school for the blind, where he did research on Braille, still feels like home to me, like a humble paradise, as little as I could ever stand schooling.

In the center of town stood a classic rough-hewn Romanesque courthouse, with an equestrian statue of Confederate general John Hunt Morgan out front. A few blocks further along Main Street lay the train station waiting shed, and in that same stretch Mains two cozy, plush movie houses, the Kentucky and the Strand, which were staffed with pimpled ushers and showed first-run double features and cartoons, including Saturday-morning all-cartoon programs. By the bus stop there was a Woolworths dime store and a bakery that sold glazed doughnuts warm from the oven.

The limestone, pillared public library was in the middle of a heavily wooded park a few blocks behind the courthouse, across the street from Transylvania College (the first college west of the Allegheny Mountains). Inside, the library was marble, with sunshine from the second-story skylight brightening the ground floors central information desk; whispers, shuffling shoe steps, and shelves and shelves of musty-smelling, dimpled green or orange library-bound books free for the taking.

On the outskirts of town were drive-in movies and an amusement park. The family would take grocery bags full of homemade popcorn to the drive-in, and, on the way home, my sister and I fit lengthwise, head to feet, in the backseat, asleep. Every once in a while wed get to visit Joyland, where there was a wooden roller coaster and a merry-go-round and a funhouse and a Tilt-a-Whirl in the midst of game booths and cotton candy and hot dog stands among huge shade trees with picnic tables below them and starlings under those.

In the suburbs the houses were unlocked. There was no air-conditioning but fans. A big warehouse in a weathered industrial neighborhood towards town stocked fresh-cut blocks of ice yanked at a loading dock by giant tongs into newspapered car trunks to power iceboxesthough most people did own an electric refrigerator by thenor to fill coolers for picnics. Youd stab the slick crystal with picks till it cracked.

Once, as a teenager in Lexington, on a hot, clear summer day, I was in a stone hut in an open field with some friends. More friends clustered in the landscape outside like some Fragonard or Watteau paintingFragonard crossed with Larry Clarkplaying and talking. A guys attention got caught by the sky. He stood in the high grass staring up, pointing and calling. We all craned our necks. There were specks in the sky floating down; chairs made of snow and snow couches touched down all around us. We were laughing and crying.

That happened in a dream a few years after Id arrived in still-lonesome New York. I woke up ecstatic and grateful, my throat constricted and eyes overflowing.

In the winter of 1956, when I was in first grade, the family moved from the cottage on Rose Street to a new suburb, Gardenside, on the edge of town.

Nearly every lot in the tract was the same small size and there were only a few house designs, mostly two-bedroom. Each house had saplings in the same two spots on either side of the walk leading up to the front door and the same type of evergreen shrubbery under the living room picture windows facing the street. Our house was just like the classic childs drawing of a home, a red-brick box under a steep shingled roof that had a chimney on one end of it.

At the bottom of the street ran a creek. Lawns descended to border both sides of it, but along its banks uncut foliage grew thick and high. The most interesting thing about it was that it wasnt man-made. The idea that you could follow its path rather than the patterns imposed by people on everything else in sight was exciting. I remember first realizing that the creek might start and end anywhere, far off, that it didnt just exist in the area I knew. The thought was a glowing little diorama hidden inside my brain, kind of like Duchamps tant donn s ( Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas ).

Gardenside had farmland at its borderstobacco and corn and livestockand woods.

Our house was one of the first in the suburb to be completed, and the ongoing construction all around us for blocks was our playground.

Next page