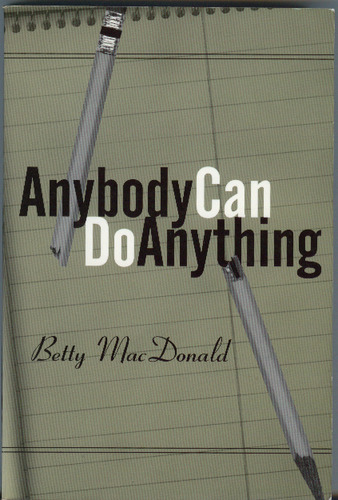

Anybody Can Do Anything

By Betty MacDonald

Original Copyright Page

COPYRIGHT, 1950, BY BETTY MACDONALD

COPYRIGHT, 1950, BY THE CURTIS PUBLISHING COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FIRST EDITION

THIS BOOK HAS BEEN PARTIALLY SERIALIZED UNDER THE TITLE, IT ALL HAPPENED TO ME

PALE HANDS I LOVE (KASHMIRI SONG) by Lawrence Hope By permission of William Heinemann & Company, London, England

AT DAWNING by Charles Wakefield Cadman

From the song At Dawning published and copyright (1906) by Oliver Ditson Company. Words reprinted by permission.

LESS THAN THE DUST by Lawrence Hope

By permission of William Heinemann & Company, London, England

THE CONGO by Nicholas Vachel Lindsay

From The Congo and Other Poems, copyright 1914, 1942 by The Macmillan Company and used with their permission.

JUDY by Hoagy Carmichael

Used by permission, Southern Music Publishing Co., Inc.

1: Anybody Can Do Anything Especially Betty

The best thing about the depression was the way it reunited our family and gave my sister Mary a real opportunity to prove that anybody can do anything, especially Betty.

Marys belief that accomplishment is merely a matter of application, was inherited from both Mother and Daddy. Mother, who has become, through the years and her own efforts, a clever artist, inspired cook, excellent gardener, qualified midwife, skillful seamstress, reliable encyclopedia of general information, book-a-day reader, good practical nurse, dependable veterinary, tireless listener, fine equestrienne, strong swimmer, adequate carpenter, experienced farmer, competent dog trainer and splendid stone mason, was working for a dress designer in Boston when she met my father, an ambitious young mining engineer who, though rowing on the crew, working all night in the Observatory and tutoring rich boys during the day, graduated from Harvard with honors in three years. The union of these two spirited people produced five children, four girls and one boy, all born in different parts of the United States, all tall and redheaded except my sister Dede, who is small and hard-headed.

Mary, the oldest of the children, was born in Butte, Montana, and indicated at a very early age that she had lots of ideas and tremendous enthusiasm, especially for her own ideas. I, Betty, the next child, emerged in Boulder, Colorado, and from the very first leaned toward Marys ideas like a divining rod toward water.

When I was but a few months old, Gammy, my fathers mother who always lived with us, sent Mary to the kitchen to ask the cook for a drink of water for me. Mary returned in a matter of seconds with the bathroom glass half-filled with water. Gammy, suspicious, asked Mary where she had gotten the water. Mary said, Out of the toilet. Gammy said, Mary Bard, youre a naughty little girl. Mary pointed at me smiling and reaching for the cup and said, No, Im not, Gammy. See, she wants it. We always give it to her.

The rest of the family proved to be a little firmer textured, not so eager to be Marys guinea pigs, so she has always generously allowed them to choose between their own little old wizened-up ideas and the great big juicy ripe tempting ones she offered.

My first memories of being the Trilby for Marys Svengali go back to that winter in Butte, Montana, when each morning Mary marched importantly off to the second grade at McKinley School, while my brother Cleve and I, who could already read and write, shuffled despondently off to Miss Crispins kindergarten, a gloomy institution where all the crayons were broken and had the peelings off.

The contrast between Miss Crispins and real school, in fact between Miss Crispins and anything but a mortuary, was heartbreakingly obvious even to four and five year olds, but the contrast between Miss Crispins and the remarkable school that Mary attended and described so vividly to us, was unbearable. Nothing ever happened at Miss Crispins except that some days it was gloomier and darker than on others and we had to bend so close to our coloring work to tell blue from purple or brown from black that our noses ran on the pictures; some days Miss Crispin, who was very nervous, yelled at us to be quiet, got purple blotches and pulled and kneaded the skin on her neck like dough; and on Fridays to the halting accompaniment of her sight-reading at the piano, we skipped around the room and sang. Miss Crispin taught us all the verses of Dixie, Swanee River, My Country Tis of Thee and Old Black Joe, and for-the bottom rung on the ladder to enjoyment, I nominate flapping around the room dodging little kindergarten chairs and singing Old Black Joe.

Compare this then to the big brick school that Mary attended where everyday occurrences (according to Mary and Joe Doner, a boy at school called on so often to prove incredible stories that If you dont believe me, just ask Joe Doner has become a family tag for all obvious untruths) were the beating of small children with spiked clubs, the whipping of older boys with a cat-o-nine-tails in front of the whole school, the forcing of the first graders to drink ink and eat apple cores, the locking in the basement of anyone tardy, and the terribly cruel practice of never allowing anyone to go to the bathroom so that all screamed in pain and many wet their panties.

Naturally Cleve and I believed everything Mary told us, but also naturally, after a while, we grew blas about the continual beatings, killings and panty wettings that went on in the second grade at real school, so Mary, noting our waning interest, started the business about the sausage book and for months kept us feverish with curiosity and acid with envy.

One snowy winter afternoon she came bursting in from school, glazed with learning, but instead of her usual burden of horror stories, she was carrying a big notebook with a shiny, dark red, mottled cover, like salami. Look at this, she announced to Gammy and Mother. I call it my sausage book and I put everything I learn in it. See! Carefully she brushed the snow off her mittens, turned back the shiny cover and with great pride pointed to the first page. Thats what we did in school today, all by ourselves, without any help, she said.

Why, thats beautiful, dear, Mother said. Just beautiful! Gammy echoed and Cleve and I crowded close to see what was beautiful. Immediately Mary grabbed the book, snapped it shut and put it behind her back. Hey, we want to see in your sausage book, Cleve and I said. Mary, in a maddeningly sweet, sad way, said, Id like to show it to you, Cleve and Betsy, I really would, but Miss OToole wont let me. She said its all right to show our sausage books to our mothers and fathers but never ever to our little brothers and sisters, Mother and Gammy laughed and said, Nonsense, so Mary stamped her foot and said, If you dont believe me, just ask Joe Doner.

Day by day Mary built up the importance of the sausage book until I got so I dreamed about it at night and thought that I opened it and found it full of paper dolls and colored pencils. But no spy was ever more careful of his secret formula than Mary with that darned old notebook. Sometimes she did homework in it but she guarded it with her arms and leaned so far forward that she was drawing or writing under her stomach; she slept with it under her pillow, she even took it coasting and to dancing school. She never was cross or mean about not letting Cleve and me see inside it, but persisted in the attitude that she was only obeying her teacher and trying to protect us, because she realized, even if Mother and Gammy didnt, that seeing into her sausage book might lift the veil of our ignorance too quickly and send our feeble minds off balance. Our only recourse was not to show her the pictures we made at Miss Crispins, which she didnt want to see anyway.