Contents

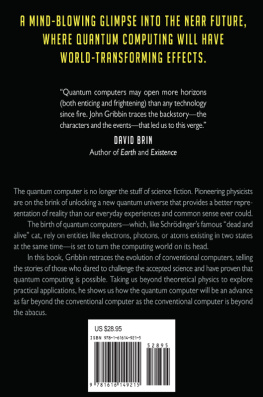

Copyright 2013 by Mary and John Gribbin. All rights reserved

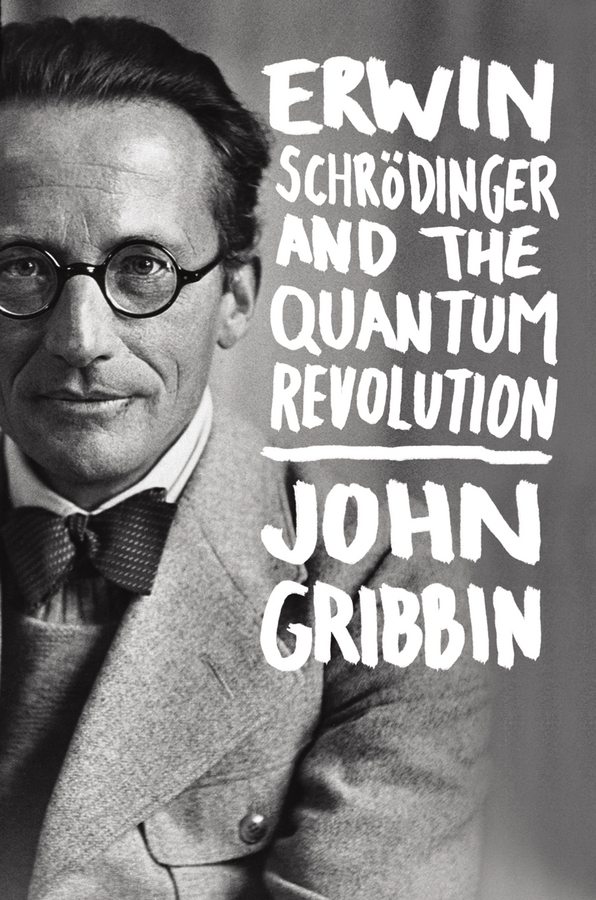

Cover Design: Tom Poland

Cover Image: Professor Erwin Schrdinger Bettmann/CORBIS

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Bantam Press an imprint of Transworld Publishers

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com . Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions .

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit us at www.wiley.com .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gribbin, John, date.

Erwin Schrdinger and the quantum revolution / John Gribbin.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-118-29926-5 (hardback); ISBN 978-1-118-33411-9 (ebk);

ISBN 978-1-118-33188-0 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-118-33519-2 (ebk)

1. Schrdinger, Erwin, 1887-1961. 2. PhysicistsAustriaBiography. 3. PhysicsPhilosophy. 4. Quantum theory. I. Title.

QC16.S265G75 2013

530.092dc23

[B]

2013025742

For Terry Rudolph,

even though he wont read it

We must not forget that pictures and models finally have no other purpose than to serve as a framework for all the observations that are in principle possible.

Erwin Schrdinger, Frankfurt, December 1928

His private life seemed strange to bourgeois people like ourselves. But all this does not matter. He was a most lovable person, independent, amusing, temperamental, kind and generous, and he had a most perfect and efficient brain.

Max Born, My Life (1978)

Preface

While writing my book In Search of the Multiverse , I came across a prescient but little-known piece of work by the quantum pioneer Erwin Schrdinger, which pointed the way, had anyone taken notice of it at the time, towards the very modern idea of a plurality of worlds, separated from one another not in space but in some other senseparallel universes, in the language of science fiction. There was no suitable way to squeeze this historical dead end into that book, but it reminded me that Schrdinger was a man of many talents, and well worth being the subject of a popular biographya biography which would give me a chance to dust down that forgotten piece of work and give it the recognition it deserves, set in the context of Schrdingers life and work. The more I looked into his life, the more remarkable it seemed; I hope you agree that his is very much a story worth telling.

Acknowledgements

Although her name does not appear on the cover of this book, Mary Gribbin played an invaluable role as a researcher, digging up details of Schrdingers life and liaising with libraries and research institutions. As ever, we are both indebted to the Alfred C. Munger Foundation for financial support. Our special thanks go to the following people who and places that helped us, over the years, in our search for Schrdinger: Michel Bitbol; Dominic Byrne; John Cramer; Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies; Einstein Archive, Princeton; Johns Hopkins University Archive; Sir William McCrea; Oxford University Archive; Rudolf Peierls; Terry Rudolph; Schrdinger Archive, Alpbach; Schrdinger Archive, Vienna; Christine Sutton; University of Berlin Archive; University of Wisconsin Archive; Vienna University Archive.

Introduction

Its Not Rocket Science

Rocket science is the purest expression of the laws of physics spelled out by Isaac Newton more than three hundred years ago, often referred to as classical science. Newton explained that any object stays still or moves in a straight line at constant speed unless it is affected by an outside force, such as gravity. He taught us that if you push something it pushes backaction and reaction are equal and opposite, as when a rifle kicks back against your shoulder while the bullet flies off in the opposite direction. He also gave us a simple law of gravity, explaining how the force of gravity depends on mass and distance. The action and reaction bit is at the heart of rocket science. A rocket throws out stuff (usually hot gas, although in principle machine-gun bullets would do the trick) in one direction, and the reaction makes the rocket accelerate in the opposite direction. When the motors are not running, the spaceprobe drifts in what would be a straight line except for the influence of gravity. All sound Newtonian physics, and not really very difficult to understand.

Classical science describes an utterly predictable world. It is possible, for example, to work out exactly how much rocket thrust in what direction is needed to set a spaceprobe with a certain mass on a trajectory, falling through space under the influence of gravity, that will take it to intercept the planet Mars at a precise date months in the future. Assuming their engines work properly, spaceprobes only miss their target when somebody gets the sums wrongwhen there is human error.

For centuries after the time of Newton classical science posed a real problem for anyone who believes in free will. In principle, if you knew the position and speed of every particle in the Universe, including the atoms we are made of, at any chosen moment of time, it would be possible not only to predict the entire future of the Universe, but to reconstruct its entire history in exquisite detail. Leaving aside the practical problems of actually doing this, it seemed to imply that everything, including human behaviour, was pre-ordained. But then came quantum physics.

Quantum physics is not like classical physics. It is definitely not rocket science; its much harder to understand than that. It took many top scientists, working over the first three decades of the twentieth century, to work out just what quantum physics is, and when they did find out some of them, including the subject of this book, didnt like what they had found.