Contents

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Text John Gribbin and Mary Gribbin, 2017

Cover design by Jonathan Pelham

The authors assert their moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008220594

Ebook Edition May 2017 ISBN: 9780008220600

Version: 2017-04-27

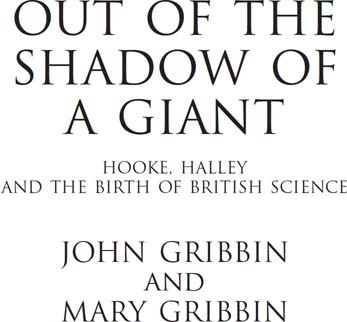

The seed from which the idea for this book grew was planted during a conversation with Lisa Jardine at the Royal Society, following a talk by one of us (JG). We got to speculating about how science in Britain might have developed if Isaac Newton had never lived. Our conclusion, such as it was, was that although Newton had inspired a great advance, and fully justified his status as the scientific giant of his day, there were only slightly lesser men who would have been well able to set British science off on the road it followed after Newton, although the journey down that road might have taken a little longer. Two men, in particular, stand out as thinkers who made major contributions, not just to scientific discovery but also to the development of the scientific method itself, who lived and worked in the shadow of Newton. They have by no means been forgotten, but even many of the people who still know the names of Robert Hooke and Edmond Halley have little knowledge of the remarkable breadth and depth of their work. Hooke is remembered for a rather mundane law describing the behaviour of a stretched spring; Halley for the comet that bears his name, but which he did not discover. Their other achievements, however, are so important that between them they arguably add up to the scientific equivalent of another Newton. So rather belatedly (and, alas, too late for Lisa Jardine to see it) we have decided to attempt to bring them out from the shadow of Newton, and present the men and their achievements in all their glory.

Thanks to the University of Sussex for providing us with a base from which to work, the Royal Society, Royal Astronomical Society, British Library, British Museum, Public Record Office, Science Museum Library Wroughton, Kings College, Cambridge, and the university libraries in Oxford and Cambridge for access to their archives, and to the Alfred C. Munger Foundation for financial support.

Isaac Newton famously commented that if he had seen further than other people it was by standing on the shoulders of giants. But even within his own lifetime, and increasingly since then, Newton was widely acknowledged as the greatest of all scientific giants, to such an extent that the remarkable achievements of his colleagues and contemporaries are often overlooked. Two of the pioneering scientists who lived and worked in the shadow of Newton would each have been regarded as giants in their own right if he had not been around, and it is our intention to bring them out of Newtons shadow to put their achievements in perspective. They are (in chronological order) Robert Hooke (16351703), who was slightly older than Newton (16421727), and Edmond Halley (16561742), who outlived Newton. Their overlapping lives neatly embrace the hundred years or so during which science as we know it became established in Britain.

But what of Newton? He was, to say the least, economical with the truth, and attempted to write Robert Hooke out of history, having borrowed many of Hookes best ideas. It has been established, for example, that the famous story of the falling apple seen during the plague year of 1665 is a myth, invented by Newton to bolster his (false) claim that he had the idea of a universal theory of gravity before Hooke. In fact, Hooke described such an idea, and the rule that every object (such as a planet) moves in a straight line unless acted upon by some outside force (ironically, now known as Newtons First Law), in the mid-1660s, when Newton was an unknown and very junior member of Cambridge University (he only graduated in 1665). Until Hooke mentioned these ideas to Newton several years later, Newton subscribed as surviving documents show to the idea that planetary motion was caused by whirlpools in some kind of fluid filling the Universe. Newton also lifted much of Hookes work on light and colours, and Newton published (significantly, immediately after Hookes death) as his own theory of heat, an idea that has been described by historian Clara de Milt as very, very like Hookes earlier work. In one respect, though, Newton was a better scientist than Hooke: he was a brilliant mathematician. And he outlived Hooke, so he had the last word until now.

We have not attempted to provide complete biographies of our subjects, who have been well served in that regard by Lisa Jardine (Hooke) and Alan Cook (Halley); our focus is on their scientific achievements, and how these were fundamental to the development of science in England. But there is, we hope, enough biographical background here to give some insight into the kind of people they were, and how they were both, in their different ways, products of the society they lived in.

Hooke has been described as Englands Leonardo, a polymath whose achievements extended far beyond the realm of science. He came from a poor but respectable background, the son of a curate on the Isle of Wight. With the aid of a modest inheritance, he was able to attend Westminster School, and go on to Oxford as a choral scholar without having to pay fees. This was in 1653, during the Parliamentary Interregnum, and since music was banned in church services at the time he got the scholarship without having to sing for it. He eked out a living by acting as a paid servant for one of the wealthier undergraduates, normal practice at that time. He then moved on to become assistant to Robert Boyle, the father of chemistry. It is now widely accepted that it was Hooke who discovered what is now known as Boyles Law of gases; Hooke was the only one of Boyles various paid assistants to be credited by name in his writings. Through Boyle, Hooke became a member of the inner circle of British scientists of the day, and became the first Curator of Experiments at the Royal Society. He was the man who made the Society a success, but (perhaps because of his humble background) he was always touchy about priority and famously got involved in rows with Newton and the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens. Hooke pioneered the use of the microscope, wrote the first popular science book (praised by Samuel Pepys), made astronomical observations, and kept the Royal running. One of his great friends was Christopher Wren, and after the Fire of London the two of them worked together on the rebuilding of the City many Wren churches are now thought to be Hookes work. Hooke was the best experimental scientist of his time, the leading microscopist of the seventeenth century, an astronomer of the first rank, and developed an understanding of earthquakes, fossils and the history of the Earth that would not be surpassed for a century.

Next page