Neil Wilson Publishing Ltd

www.nwp.co.uk

Text the Estate of Alastair Dunnett, 2011

Introduction Ninian Dunnett, 2011

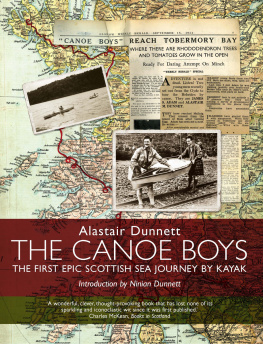

First published as Quest by Canoe, 1950.

Republished as Its Too Late in the Year, 1969

Republished as The Canoe Boys in 1995.

This edition published in May 2007 and

reprinted in April 2009, March 2011.

The author asserts his moral right under the

Copyright, Design and Patents Acts, 1988

to be identified as the Author of this Work.

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

Print edition ISBN: 978-1-903238-99-8

EBOOK ISBN: 978-1-906476-71-7

CONTENTS

To

James S.Adam (Seumas)

who went further

and to those of the Claymore

John Scott Burt

James Brown MacDougall

Robert MacLean

Reviews of previous editions of The Canoe Boys:

One of the most unusual travel books published in a long

time ... Only those who have sailed among the Western Isles

in substantial craft can realise the full implication of a trip there

in a frail canoe. Such a method of voyaging in these waters seems

fantastic. Yet it was done ... absorbing reading.

Glasgow Herald

A daring feat.

Sunday Times

... spacious, humorous, penetrating log-book ... the

observant eye as well as the racy pen.

New Books

Adventure surely was part of the story, and that aspect of it is

given full prominence. But there was more to it than adventure;

there was a purposeful determination to discover personally the

causes contributing to the depopulation of the Highlands.

Sunday Mail

The purpose and spirit of the book stand forth inspiringly.

Daily Record

A memorable cruise ... he hotly denies that Highlanders are sly

neer-do-weels; he rails at authority for its neglect of Gaeldom.

Evening Dispatch

As a record of what must have been a very hazardous

voyage, this is first-rate and exciting reading. It is, in the

highest sense, a fine travel book.

Evening Citizen

The charm of the book as a record of experience does not

obscure the value inherent in its assessment of conditions and

potentialities in a beautiful but long neglected area.

Scotsman

INTRODUCTION

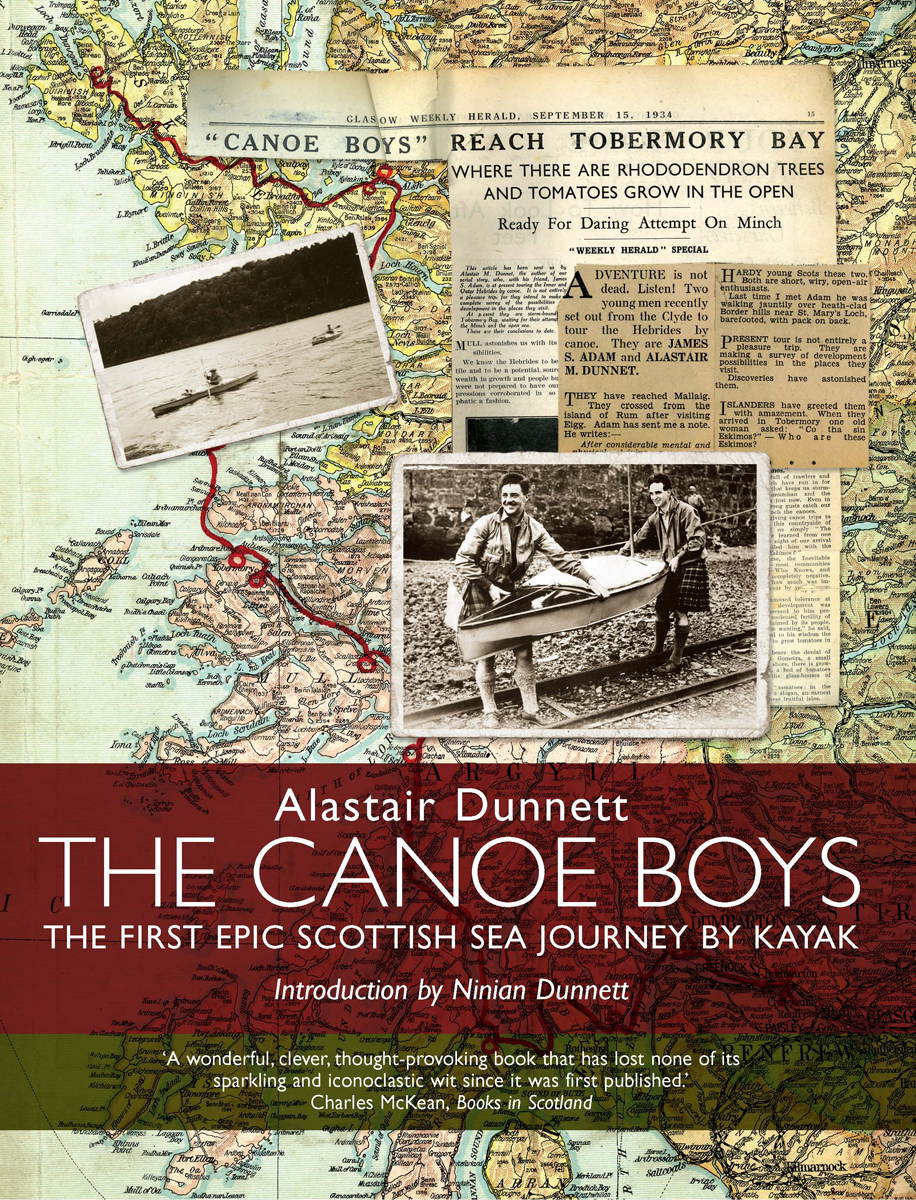

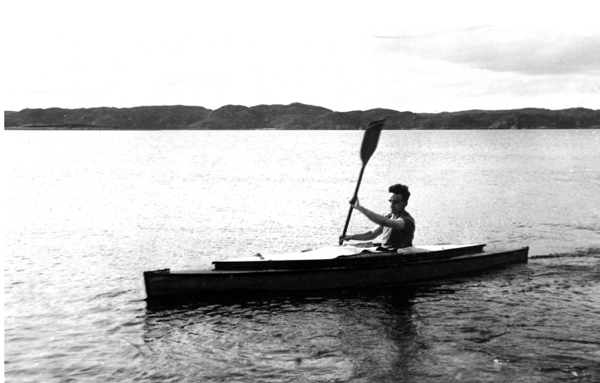

Late in the 20th century, an elderly Scottish journalist found himself welcoming a new sort of visitor to his Edinburgh home. Every so often, there would appear on the doorstep a particular breed of far-flung adventurer. They were travelling (perhaps surprised to find from Neil Wilsons 1995 reprint of this book that the opportunity was still there) in the hope of meeting a figure of legend: one of the canoe boys.

There was something of a full circle in this, for it was as canoe boys that my father and his friend James Adam had first known celebrity, among the Hebridean community who watched for their paddling silhouettes on the horizon more than 70 years ago. To be graced with the title once more, near the end of his life, was for him as fine an accolade as the late knighthood, honorary doctorate and other tributes which rounded off a life of achievement.

In fact, the three-month journey undertaken by two men in their mid-twenties had been a touchstone throughout their long lives.When Alastair Dunnett wrote this book at the mid-point of the 20th century it was a reaffirmation of the values underpinning a career as one of Scotlands most distinguished newspaper editors. Even then, though, most of his adult life separated him from the remembered events of the narrative. The world had changed, the war years had taken their toll and personal nostalgia was already one of the elements of the story.

So there was much to talk about to the young voyagers who settled themselves in the cosy Merchiston sitting-room with a glass of Famous Grouse. Often they brought their own stories, like Brian Wilson, whose Blazing Paddles: Scottish Coastal Odyssey was published a few months before my father died. But they all came to listen, too. The sporting achievement of James (Seumas) and Alastairs trip during a stormy autumn, with negligible experience, equipment now seen as primitive and no precursors for reference or encouragement, has made it a milestone in British canoeing history.

The Canoe Boys has earned its place in the literature, too. In the years it has been out of print, its incarnations as Quest by Canoe (1950) and Its Too Late In The Year (1969) have been highly prized, and its reputation nurtured by reference and quotation in other canoe books like Robin Lloyd-Jones Argonauts of the Western Isles (1989). At the time of writing it has a lively presence among enthusiasts on the internet: you will find its recipe for brose at www.canoecampingclub.co.uk, or get access to the book itself through the library of Ribble Canoe Club.

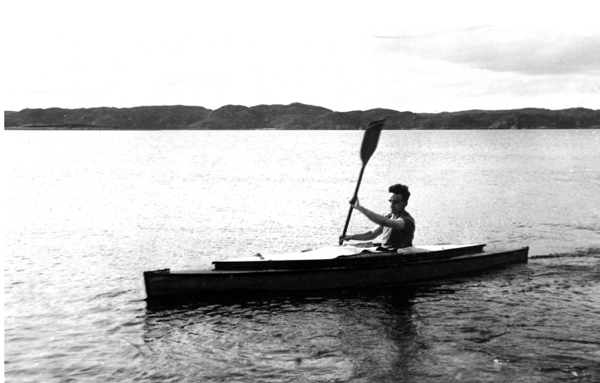

Seventy-five years ago, the canoe boys experiments on the water had begun as an extension of their forays into the bens and glens. These were the days when the hordes who had flocked to industrial Glasgow to bend their shoulders for the second city of the Empire were beginning to rub their eyes and discover the fabulous landscape on their doorstep. Alastair Dunnett and Seumas Adam were among them as they hiked, hitched and bussed out of the city to Loch Lomond and the Highlands. Here the pair joined the work of establishing camps like Auchengillan, where the wide-eyed new ramblers could make the most of often frugal resources.

The hills, though, were also a deeply personal matter. As a junior bank clerk unhappily trammelled by the bowler-hatted urban grind, Alastair would escape to the Highlands with just a heavy canvas backpack, tent and blanket. His journal entry for the final night of a lone and snowy May hike from Balmaha to Bridge of Orchy in 1926 youthfully frames the lament of all those whose wings are clipped by circumstance:

Tomorrow my feet will walk a citys pavements. Tomorrow I shall know again the full horror of respectability.

Tomorrow, pilloried in collars, surmounted by unyielding headgear, I shall prepare to shoulder again my infinitesimal burden of responsibility in the financial transactions of a wearied world. But tonight tonight I am free. I am cold. I shall probably soon be wet. But I am happy. And to the servants of nature who have made me so to the rain, the snow, to the smoke of my fire, to the suns brief appearance, to the cuckoo, whose song has haunted me since my start to them all, my heart sings Good night.

On this trip, moved by his first sight of the view from Ben Lomond (he wrote later) he had pledged a sort of commitment to the landscape, and, aged 17, became knit forever to my native land.

I had tears to shed, he recounted, recalling that early ascent more than half a century later, just as women do at weddings and probably for much the same reason.

It was rare though, in the years that followed, that Alastair would travel alone. The scout movement had been a welcoming escape route from the city for a generation of working class kids in the Depression, and though he joined it reluctantly and eventually repudiated it, it was where he would meet the closest friends of his life, and develop some of its guiding ideas. Over the next 10 years, this tight-knit band would be his allies on some of its greatest ventures.