Copyright 2010 Omnibus Press

This edition 2010 Omnibus Press

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 1415 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ)

ISBN: 978-0-85712-222-3

The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Visit Omnibus Press on the web: www.omnibuspress.com

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

For all the children who never got to know their fathers

And for Campbell, may that never be the case

Foreword

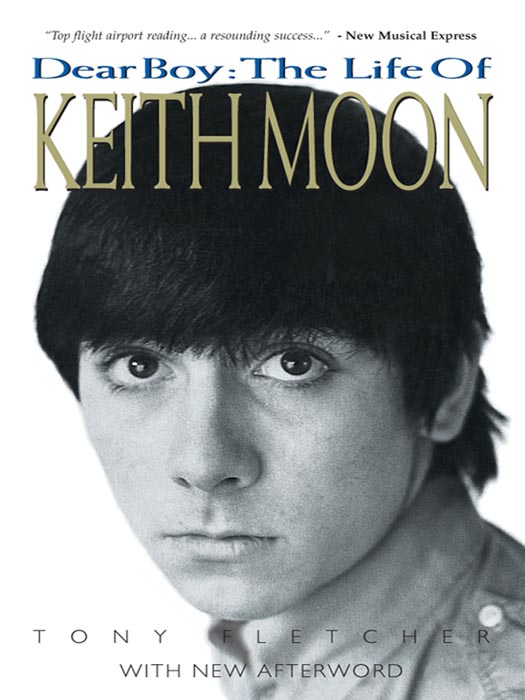

H ow do you attempt to capture an exploding time bomb? These were the first words put to me by one of the vast number of people I talked to while researching the life of Keith Moon. They were spoken by Mark Volman who, as a member of the Mothers of Invention and half of Flo and Eddie, came to know Keith through their appearance in a Frank Zappa movie and then during Moons three years self-destructive downswing in Los Angeles. But Volmans was merely the most succinct of many similar observations that revealed much about Keiths evasive character in a few words while emphasising the difficulty of saying everything about him in a biography.

Even those closest to him in life sometimes found themselves stymied when attempting to define him in death. It just felt like he was going to explode, his former wife Kim McLagan, who through ten years of a turbulent personal relationship came to know the adult Keith best and worst said to me at one stage. There was just so much in there.

On another occasion, she told me, He was a star, only partly referring to him as a mortal celebrity. Her real meaning was revealed when she continued, And he illuminated so many other lives.

I prefer to think of him as a comet, blazing through and enlightening our earthly experience while burning himself put in the process. But Ill take any form of cosmic comparison, including the double definition of the word star and the lunar association of his name, if only because Keith Moons existence was so utterly and in all senses out of this world.

To be sure, the personality traits that mark us as individuals can usually be traced back through our bloodline. Musical prowess is often hereditary. Alcoholism is now recognised as a genetic illness. Spousal abuse tends to be part of an ongoing, hard-to-break generational cycle. Tendencies toward comedy, acting and public performing are all usually attributable, at least partially, to ones parents and upbringing.

Not so with Keith. There was absolutely nothing in his family background that gave even an inkling as to what his life would become. Quiet and unassuming, disciplined and accepting, teetotal (yes]), loyal, and unquestionably loving, his parents were the living embodiment of every governments dream subjects.

The subsequent life of Keith John Moon the blazing comet, the shining star, the full moon brightening the night sky had nothing, and yet everything, to do with this almost crushing normality. From the earliest age, Keith Moon proved himself an exception to all known rules, and upon discovering this about himself, he made it his purpose in life to challenge them in everything he did. He revolutionised the concept of the drummer in rocknroll and pop music by rejecting the previously accepted constraints, leading from the back as was almost unheard of rather than offering mere support as was then the convention, filling spaces that had always been left open, leaving gaps where usually lay the beat. He achieved greater international fame than his instrument was meant to inspire, only to treat that celebrity status as an ongoing opportunity to send up the whole notion. He sneered at the dominant British stiff upper lip, while appropriating it so effectively as to delete his working-class background at will; he threw his head into the cavernous jaws of certain disaster time and again, including tempting fate with an almost unparalleled intake of alcohol and drugs, and emerged on every occasion (but the last) just about whole, beckoning the world to laugh with him at his apparently charmed existence. He never encountered a situation so formal that he could not denoble it by stripping naked, never met an important person he could not cut down to size with an instant one-liner, never knew the meaning of the word embarrassment.

Money he treated with contempt. Certainly he craved it, but he ridiculed it too: the higher his income, the greater his debts, the very antithesis of his parents generation and their insistence on living within their means. Beautiful houses, fanciful investments and luxury personal possessions were acquired and dismissed or destroyed so rapidly as to become worthless. Hyperactive and peripatetic, he simply could not stay still. Keith Moon was forever running, always one step ahead of reality, his whole life a desperate, tragic battle to escape the normality into which he was born.

Or so I believe. The biographer takes on a Herculean task when inviting himself into the life of someone so complex as Keith Moon, a modern legend about whom so much has been said and written and yet who his own parents did not really know, neither his wife nor his later fiance could control, his daughter was scared of and his fellow band members, much though they loved and suffered him, have never fully agreed upon.

But its a task I must accept if I am to do my subject any justice, and more than that, its one I sought out for myself. Like so many music fans, I have entertained a fascination with Keith Moon since his image first implanted itself in my impressionable young mind. (And what was that first impression? A drunken, toothy grin beckoning from the inside of a music weekly? A reprinted publicity still of the handsome teenage mod? A live clip of his on-stage primal energy from some long-forgotten Seventies television show? A frenetic roll through that endless sea of tom-toms that would have distinguished a Who song across the airwaves? Or a story of the great mans excesses heard from elders in the school playground or on the football terrace and repeated as indisputable fact? All these and more, I suspect, for no one image takes claim as I write.] That I saw him once in his element (Charlton, 1976) and met him once at his most unguarded (London, August 1978) established his heroic status in my mind at the time, but that alone was not enough to keep him there: through my work (and play), I soon had met so many past idols and future stars that fame no longer garnered respect. Yet Keith Moon, his young death perhaps a contributory factor, only grew upon me as an icon.

And as to me, so to many others. Come the Nineties, and I found that mention of his name elicited a stronger reaction than ever particularly from a generation that had come of age after his death. His image graced album sleeves (the Rolls Royce in the swimming pool on Oasis