Once again, I am deeply indebted to scores of people who have helped me to write this book by generously providing guidance, hospitality, gentle mockery, food and fellowship, as well as access to documents, photographs, recorded interviews and memories. I am particularly grateful to the families of the agents and their case officers, German as well as British, who provided me with so much valuable material: Fiona Agassiz, Robert Astor, Marcus Cumberlege, Gerry Czerniawski, Prue Evill, Jeremy Harmer, the late Peggy Harmer, Anita Harris, Caroline Holbrook, Alfred Lange, Karl Ludwig Lange, David McEvoy, Belinda McEvoy, Marco Popov, Misha Popov and Alastair Robertson. I have benefited greatly from the expertise of a number of brilliant historians and writers, including Christopher Andrew, Michael Foot, Peter Martland, Russell Miller, Nigel West and Paul Winter. My thanks to Jo Carlill for her superb picture research, Ben Blackmore for long hours of research at Kew, Mary Teviot for her genealogical sleuthing, Manuel Aicher for research work in Germany, Jos Antnio Barreiros in Lisbon, and Begoa Prez for her help with translations from the Portuguese. I am also grateful for the advice, help and encouragement of Hugh Alexander, David A. Barrett, Paul Bellsham, Roger Boyes, Martin Davidson, Sally George, Phil Reed, Stephen Walker, Matthew Whiteman, and all my friends and colleagues at The Times . I owe a particular debt to Terry Charman, Robert Hands and Mark Seaman for reading the manuscript and saving me from some excruciating howlers. The remaining errors are all my own work. To those who prefer not to be named, I am deeply grateful for all your help.

It is a pleasure and a privilege to be published by Bloomsbury; my thanks go to Anna Simpson and Katie Johnson for their unfailing efficiency and patience, and to Michael Fishwick, loyal editor and dear friend. My agent, Ed Victor, has been a rock of support throughout my writing career. My children have kept me sane through another book with their support and good humour; and to Kate, as ever, all my love.

In German eyes, Agent Brutus had proved himself the noblest Roman. In the wake of D-Day, having failed to predict the real invasion and pumped his handlers full of lies about the false one, he could do no wrong. Most Secret Sources showed that his reports were being studied not only by the operational sections, but by the most prominent persons in Berlin, including Hitler and Goering. German intelligence regarded him as an oracle, a sage: We shall presently reach a stage where high-level questions on military matters are addressed personally to Brutus, Astor crowed. In July 1944, a flying bomb landed in Barnes in southwest London, blowing out the windows of 61 Richmond Park Road, and leaving Monique Czerniawski with serious facial injuries. MI5s bean-counters agreed to pay the 50 needed for plastic surgery, noting that Czerniawski had worked valiantly for us over a long period of time without receiving any remuneration.

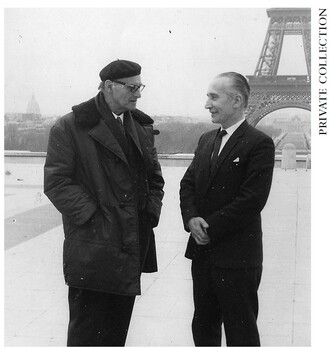

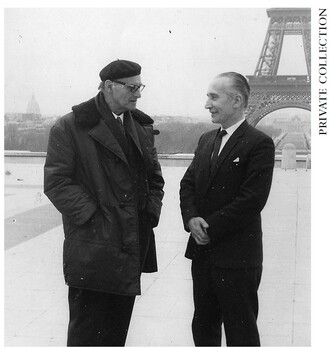

In his assumed role as a secret international statesman, Czerniawski bombarded the Germans with unsolicited and unhelpful advice. Nobody here believes any more in a German victory, he told them. As a Pole, can I suggest that neither is it in our interest nor in yours [that] the Russians be allowed to occupy Central Europe... I believe this is a good psychological moment for attempting to reach an agreement with the Anglo-Saxons, and I am inclined to think they may accept your military propositions. The reply came back from Reile: Once again I thank you with all my heart for your excellent work. I have passed on all your political propositions, especially concerning your country, recommending them to accept them. Still hungry for an Iron Cross, Astor longed to deploy Czerniawski on one final deception, and suggested parachuting him into France ahead of the retreating German forces. Once there, he would contact German intelligence and explain that he had been sent by the British to recruit and organise an intelligence service behind the lines and offer to work for Germany, again. He would then be in a position to receive the Germans deception plans which might reveal their real intentions. No other spy had made so many journeys back and forth between loyalty and betrayal: first as an agent in occupied Paris; then a double agent for the Germans; then a triple agent, working for the Allies once more; he now offered to go back to France, as a quadruple agent, while in reality a quintuple agent, still working for Britain.

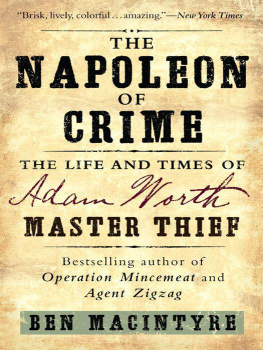

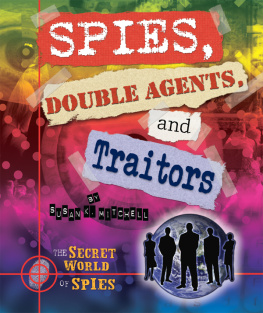

Roman Czerniawski ( right ) and Hugo

Bleicher, the German intelligence

officer who captured him, reunited in

Paris in 1972.

By the terms of the deal with the Germans, Czerniawskis family and former colleagues in the Interalli network would not be harmed if he played his part. When Paris was liberated, so were the hostages. Before leaving, the Germans left a final token of their faith. Beside the road out of Paris, Reile dug a hole, in which he buried a new radio transmitter and 50,000 French francs, in the expectation that if the indefatigable Agent Hubert arrived with the advancing Allied troops, he would wish to keep in touch an act which hardly squares with Reiles later claim that he knew Czerniawski was a double agent. On Nationale 3 between Paris and Meaux there is a milestone which, according to the inscription upon it, is 2.3 km from Claye and 12.4 km from Meaux. The equipment is concealed 5 metres from this stone in a ditch under a mark on the grass, buried 10 cm deep. The German retreat was too swift to put the Quintuple Cross plan into operation, and Czerniawskis parting gift from his German spymaster was forgotten. In the 1960s, Route Nationale 3 was widened, covering over the hiding place. Every day, thousands of motorists on the road from Paris to the German border pass over this buried memento to Agent Brutus.

After the war, Roman Czerniawski settled in Britain. Though he thought a Polish government set up by Moscow is a degree better than having no Polish government at all, he could never return to his homeland with a communist regime in power. He was secretly appointed OBE for his wartime role. He became a printer, settled in West London, amicably divorced Monique, remarried, divorced, married again. He adored cats, and in old age he liked to sit in his front room, watching James Bond films, with his cats. The cat population in the Czerniawski household eventually reached thirty-two. He never lost his heavy Polish accent, or his whole-souled Polish patriotism, and he intrigued to the end, spending his final years secretly working for the Solidarity movement. He died in 1985, aged seventy-five.

Mathilde Carr, once Czerniawskis partner in the Interalli network, was extradited to France in January 1949 after six years in British prisons, and charged with treason. The trial of The Cat was a sensation. She sat wordless throughout, with a withdrawn air of detachment, as thirty-three witnesses came forward to denounce her for sleeping with the enemy. The prosecution summed up with an entry from her own diary from the night she first made love to Hugo Bleicher: What I wanted most was a good meal, a man, and, once more, Mozarts Requiem . Mathilde was sentenced to death, later commuted to hard labour for life. In Rennes prison she suffered cat-filled nightmares which turned into hallucinations.

She was finally released in 1954. A few months later she was approached by Bleicher, who had served time in prison and was now running a tobacconist in Wrttemberg. He asked her to write a book with him, a harmless literary collaboration, he called it. She had done enough collaborating with Bleicher, and wrote her own book, I Was The Cat , insisting that her crimes had been committed to achieve a noble, patriotic ideal. Few believed her. She died in 1970, a recluse. Mathilde Carr was either treacherous, or just desperately unlucky. Like Czerniawski, she claimed she had only worked for the Germans in order to betray them. As her lawyer argued, at certain moments in the life of a spy, the double-cross is all part of the game. Czerniawski felt a residual sympathy for his fellow spy, forced by war to make impossible choices in circumstances not of her making. Years later, he was still troubled by her fate. I dont know how I would have behaved, he wrote. Do you?

Next page