Contents

For Shannon Halwes, without whom this book would not exist

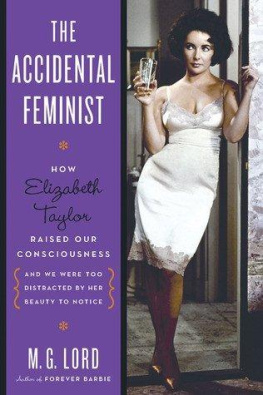

YOU COULD SAY it began in 1944 with National Velvet , when Elizabeth Taylor, age twelve, dressed as a boy and stole Americas collective heart. By it, I mean the subversive drumbeats of feminism, which swelled in the stars important movies over decades from a delicate pitty-pat to a resounding roar.

Feminism may not be the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the name Elizabeth Taylor. But it might if you share your definition with writer Rebecca West: I myself have never been able to find out precisely what feminism is. I only know that people call me a feminist when I express sentiments that differentiate me from a doormat.

Elizabeth Taylor has been called many things, but never doormatnot in life and not on screen. (Except in Ash Wednesday , her 1973 movie, where that was the point.) The characters she played were women to be reckoned with. And many of her rolesthe great and the not-so-greatsurreptitiously brought feminist issues to American audiences held captive by those violet eyes and that epic beauty. While I know that writers and directors create movies, stars create a brand. And the Taylor brand deserves credit for its under-the-radar challenge to traditional attitudes: a woman may not control her sexuality; she may not have an abortion; she may not play with the boys; she may not choose to live without a man; she must obey her husband; and should she speak of unpleasantness, she will be silenced.

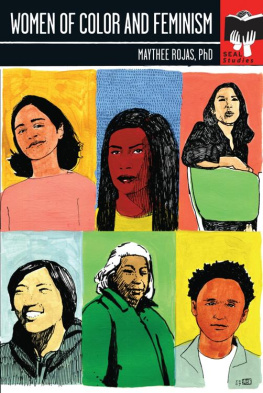

Although I love quoting Wests glib retort, feminism is, in fact, a tricky thing to define, because its self-identified adherents dont always march in ideological lockstep. To theorist bell hooks, it is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression. To writer Marie Shear, it is the radical notion that women are people. To columnist Katha Pollitt, it is a social justice movement dedicated to the social, political, economic, and cultural equality of women and men, and to the right of every woman to set her own course. To author Rebecca Walker, it is to integrate an ideology of equality and female empowerment into the very fiber of my life.

Throughout its history, feminism has never been either monolithic or static. During the twentieth century, its concerns changed from suffrage, temperance, and the repeal of primogeniture laws to reproductive rights, workplace equality, and protection from discrimination based on gender or sexual orientation. Betty Friedan kicked off the so-called second wave of feminism with her 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique. In 1971, Gloria Steinem, another second-wave figure, launched Ms. magazine to address ongoing feminist issues. But during the magazines first decade, its readership, like feminism itself, was largely white, heterosexual, and middle class.

In the 1980s, novelist Alice Walker, a Ms. contributor, broke with this movement, urging feminists of color to identify as womanist. A decade later, her daughter Rebecca Walker rejected the womanist idea, declaring herself and those who share her views to be the third wave. Third-wave feminists pitch a big tentlarge enough to contain diverse ethnicities, sexual preferences, and gender identities. They affirm their right to sexual pleasure, believing that desire is complex, and consensual behavior should not be policed. All feminists support equal pay for equal work. But despite the consensus, this goal seems no closer to realization than it was fifty years ago. My understanding of feminism derives mostly from second-wave texts. But I admire efforts to make feminism more inclusive, and view controversy within its ranks as a sign of its vitality.

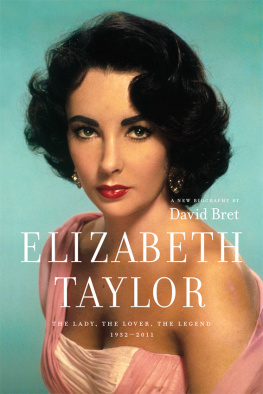

Until a few years ago, I thought the last word on Taylor was written by Camille Paglia in the 1990s. In an important essay, Elizabeth Taylor: Hollywoods Pagan Queen, Paglia identified in Taylor the ancient, mythic sexual power associated with Delilah, Salome, and Helen of Troy. But after watching Taylors key movies recently with some much younger friends, I discovered what had been hidden in plain sight: the feminist content in some of her iconic films. Be it accidental or deliberatetext or subtextthis content is very much there.

I am a baby boomer. The friends who opened my eyes are Gen X and Gen Y; our age difference changed how we saw things. On a recent Memorial Day weekend, we rented a house together in Palm Springsthat museum of midcentury Hollywood, where the very streets are named for its famous former residents: Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope, and Dinah Shore.

I am old enough to remember these performers in their heyday. My friends are not. They know them, of course, but in their later-life incarnations: Frank Sinatra as a pal of First Lady Nancy Reagan, Bob Hope as a has-been comic, and Dinah Shore as a talk show host. The Gen X friends mostly knew Taylor as the butt of Joan Riverss fat jokes from the 1980s: Taylor was the woman with more chins than a Chinese phone book. My Gen Y friends knew her only as a gay icon and an AIDS philanthropist. So when I proposed watching some Taylor DVDs that I had received as a present, my friends expected an evening of camp. Instead, we were gobsmackedboth by Taylors performances and by her movies feminist messages.

National Velvet is a sly critique of gender discrimination in sports. Taylors character, Velvet Brown, falls in love with her horsea time-honored preteen tradition. She dreams of riding the horse to victory in the Grand National, the most important steeplechase in the world. But because jockeys are required to be male, Velvet is excluded. First crushed, then emboldened, she enters the race anyway, impersonating a boy.

Following National Velvet , Taylors next significant hit was A Place in the Sun (1951), which is hard to view as anything other than an abortion-rights movie. It deals with the tragic consequences of stigmatizing unwed pregnancy. Feminism holds that women have a right to control the reproductive use of their bodies. Condemning single mothers relinquishes that power to men. Mothers were said not to give life to new individuals, so much as to give children to their husbands, so that male surnames and inheritances might be perpetuated, explains author Barbara Walker in The Skeptical Feminist.

Feminism also endorses a womans right to control her sexuality. In BUtterfield 8 (1960), Taylors character is censured not for being a prostitute but for exercising her right to choose the men with whom she will sleep. This galls the men who desire her, especially the ones she rejects. Other movies explore different feminist themes: Giant (1956) deals with the feminization of the American West; Suddenly, Last Summer (1959) portrays the callousness of the male medical establishment toward women patients; The Sandpiper (1965) pits goddess-centered paganism against patriarchal monotheism. Taylors most celebrated movie, Whos Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), may also be her most feminist. It demonstrates what happens to a woman when the only way that society permits her to express herself is through her husbands career and children.

Before going into the world to preach, zealots of all stripes retreat to the desert to meditate and prepare. After my exile in Palm Springs (getting massages and lounging by the pool), I returned to Los Angeles with a mission: learn more about these films and the circumstances under which they were made. And if their feminist content held up, spread the word.

A few years earlier, when I met Taylor, no link between her and feminism had yet crossed my mind. I did, however, see a vast disconnect between her shallow tabloid persona and the seeming depths of her real-life self. Intelligence flickered behind those lilac eyes. In October 2001, Taylor spoke at a small dedication ceremony for the Roddy McDowall Memorial Rose Garden at the Motion Picture and Television Funds Wasserman Campus, which was then a retirement home for show people. Adam Kurtzman, an artist who sculpted a bronze portrait of McDowall for the garden, invited me to the ceremony, which I could not otherwise have attended. Taylor stood next to Sybil Burton Christopher, Richard Burtons first wife, and, to my surprise, embraced her. The tabloids had written at length about the two womens enmity, which began when Richard left Sybil for Elizabeth. But their reconciliation was apparently not salacious enough to report. At the end of his life, McDowall had brought them together. Elizabeth held one of his hands, Sybil, the other, easing his passage from this world to the next.

Next page